March 2, 2016; NPR, “Code Switch”

“Beyond the Hashtags: #Ferguson, #Blacklivesmatter, and the online struggle for offline justice” is a new study by media scholars Charlton McIlwain, Deen Freelon, and Meredith Clark that does impressive work to map the development of the Black Lives Matter movement through 41 million tweets, 100,000 web links, and interviews. Using network mapping and graphing activities on timelines, the researchers were able to trace who it was that led the conversations and how they were connected.

Six “recurring communities” appeared as drivers:

- Black Lives Matter: movement activists and organizers who called for systemic change

- Anonymous and Bipartisan Report: left-leaning hacktivist collectives

- Black entertainers: celebrities who were vocally in support of the movement

- Mainstream news organizations covering the stories

- “Young black Twitter”: young black people discussing the news

- Conservatives who were in vehement opposition to the movement

Each of these communities is examined for their dynamics and roles within the report.

We cannot do justice to this report in a short newswire, but instead will provide a glimpse of the content and urge you to read it for insights and food for thought about the nature of organizing in the 21st century. The study is full of fascinating information and analyses like the following:

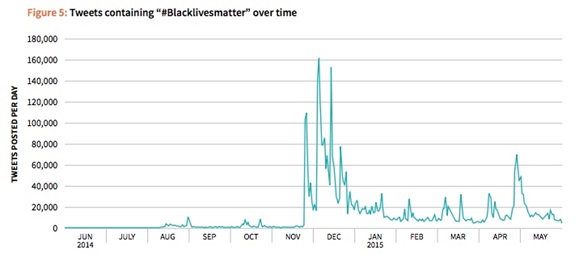

The #Blacklivesmatter hashtag was created in July 2013 after the George Zimmerman verdict. But by June 2014 it had fallen into disuse: only 48 public tweets included it throughout the entire month, an average of fewer than two tweets per day (see Figure 5). Usage increased very slightly in the weeks following Eric Garner’s death, but it was still only used 581 times during the 23 days of period 3. The hashtag appeared nearly that many times (565) on August 10 alone. Its chief promoters on that day were Black activists affiliated with established justice advocacy organizations such as Black Youth Project 100 and Million Hoodies. Within a few days, non-Black allies such as the ACLU, Dream Defenders, and activist Suey Park were using the hashtag. But it did not crack the top 10 during the Ferguson unrest, and at that point it was still mostly a statement of opinion and not yet a broad-based movement.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

#Blacklivesmatter was not widely used after then until November 24, the day St. Louis County prosecutor Robert McCullough announced that a grand jury had decided not to indict Darren Wilson for the death of Michael Brown. The previous day, the hashtag appeared in 2,309 tweets; but on that day, the total soared several orders of magnitude [sic] to 103,319. Closer inspection of the timing of that day’s tweets reveals that 90% of them were posted between the hours of 8pm and midnight Central time, coinciding with McCullough’s announcement and its immediate aftermath. This is the moment the #Blacklivesmatter hashtag first broke through to a larger audience. The most-retweeted users on this day were artists, media personalities, Internet celebrities, television writers, and ordinary people—activists were few and far between. Some of these tweets reported from protests, some declared solidarity, some criticized the media response, and some contained only the hashtag itself.

This report reflects a deep curiosity about the changing dynamics of organizing on and offline. But, says Deen Freelon, one of the authors, some things stay achingly the same. “Many of the people who rose to prominence did so out of relative obscurity,” he said.

It’s hard to game out just why certain people became influencers, and others didn’t. “You’re talking about a bunch of people on Twitter making a bunch of individual decisions about who to retweet,” Freelon said. “You’re kind of at the mercy of the cloud.”

Still, he said, when it comes to women and the movement, we could be seeing offline attitudes replicating themselves in the aggregate of the Twitterverse—like the way new stories tend to quote male sources much more often than they quote women.

“It just goes to show that when you have a big movement,” even one that’s ostensibly committed to doing things differently, and better than in the past, “you might end up falling back on these old institutional biases,” Freelon said.

—Ruth McCambridge