Shortly after the US Constitution was ratified, Benjamin Franklin penned a letter to French scientist Jean-Baptiste Le Roy, in which he said that “in this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes.” While certain, death can come in a myriad of ways, and if we peel back behind some of the leading causes of death, we find that chronic stress is linked to six of them.

Stress, like most health issues, is not equally distributed across racial groups. Black adults are 20 percent more likely to report serious psychological distress compared to white adults. Those who live in poverty and face daily struggles of overpoliced neighborhoods, underfunded schools, and lower-paid jobs are two to three times more likely to report serious psychological distress.

The psychological effects of these economic disadvantages don’t only affect parents, but they also heavily impact children, even before they are born. Studies have shown that prenatal stress can have significant effects beginning in the womb and spanning across a lifetime.

This stress, according to experts, can arise from traumatic experiences, life-changing events, or daily microaggressions. And it has negative influences not only on the outcome of the pregnancy, but also on the behavioral and physiological development of the child. Threatening situations, no matter how big or small, increase the body’s heart rate, blood pressure, and the pace of breathing.

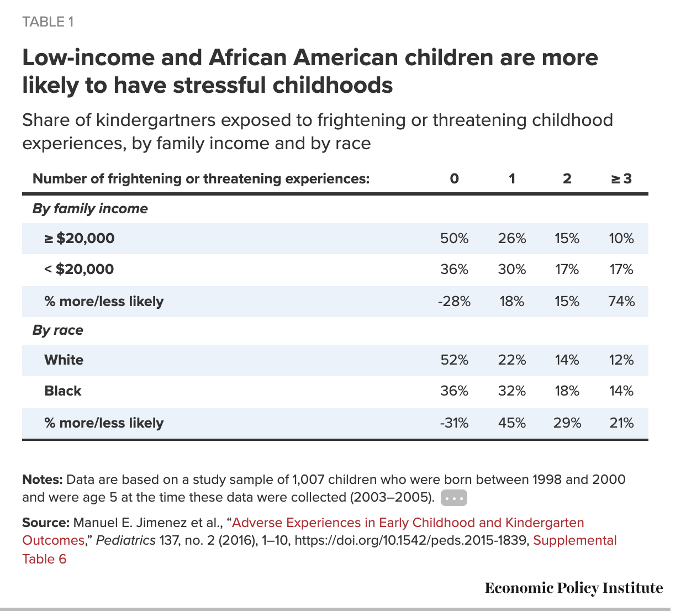

For Black families, particularly those dealing with the weight of poverty, threatening situations are plentiful. According to the Economic Policy Institute, 64 percent of Black children have been exposed to one or more frightening or threatening experiences, while only 48 percent of white children are.

When accumulated, trauma—which is the emotional, psychological, physical, and neurological response to stress—can lead to adverse effects. From daily racial microaggressions to lethal encounters, when children are frequently exposed to sustained traumatic events, they are more likely to have adverse behavioral effects and/or suffer from depression.

A study launched by Dr. Monnica Williams, a psychologist based at the University of Ottawa, found that Black students who reported higher rates of perceived discrimination had higher rates of alienation, anxiety, and stress about future negative events.

Each generation of Black Americans has faced horrific forms of racial discrimination whose scars they still carry today. The vestiges of slavery can be seen through our mass incarceration policies. Police officers, stationed around the clock in Black neighborhoods, evolved from plantation overseers. Even our economy, as detailed in the New York Times’ 1619 Project, has the fingerprints of slavery all over it. This history, and our current experiences, does not simply affect people in one single moment in time.

As a report from the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA) published last year—titled The Harm is In Our Genes: Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance & Systemic Racism in the United States—details, the trauma stemming from enslavement, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, the war on drugs, and police terror can be passed down across generations through epigenetic change.

The idea that trauma can be inherited and therefore alter how a person’s genes function (epigenetic change) is not new. It was first introduced in 1967 by Dr. Vivian Morris Rakoff, a Canadian psychiatrist who recorded elevated rates of psychological distress among the children of Holocaust survivors.

His initial research, which has been supported by subsequent studies, has found that the children and descendants of Holocaust survivors had higher levels of childhood trauma, increased vulnerability to PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), and other psychiatric disorders. In one of his earlier papers, Rakoff wrote that “the parents are not broken conspicuously, yet their children, all of whom were born after the Holocaust, display severe psychiatric symptomatology. It would almost be easier to believe that they, rather than their parents, had suffered the corrupting, searing hell.”

Other studies have examined the intergenerational effects on First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in residential schools run by the Canadian government for over a century. They found that children and in some cases grandchildren of those who attended these schools were more likely to report psychological distress, suicide attempts, and learning difficulties.

Can Reparations Heal?

Just as educators cooperated in carrying out genocidal policies through their participation in residential schools (in the United States, as well as in Canada), the medical industry has its own sorry history. For a long time, many in that field justified racial health disparities through racist and mythical biological arguments that claimed Black people were inherently inferior to white people. This US mental model was thoroughly used throughout the antebellum period and beyond. It is the root of the early 20th-century eugenics movement that led to the sterilization of thousands of Black people and was a source of inspiration for Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf and South African apartheid.

The notion that the medical industry has played a role in strengthening white supremacist theories and fortifying a racial caste system is one that I don’t believe many can argue with. The question at hand remains: what do reparations look like within a health context?

Reparations and Trauma

Large-scale trauma affects people in multiple ways, explains Dr. Yael Daniel, a prominent researcher in the field of intergenerational trauma and founder of the International Center for the Study, Prevention, and Treatment of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. It only makes sense then that our solutions are also multifaceted.

A trauma-informed framework must be applied to any reparations effort to ensure that we are creating a sustainable social policy that uproots the tenets of white supremacy. This approach, according to experts, should go seek to go beyond broad notions of trauma and address specific sociopolitical and economic drivers. Trauma-informed care within a context of reparations means employing a holistic focus not only on the economic impact of the legacy of slavery but also its psychological and health impact.

Acknowledgment of Harm

An admission that harm was done is one of the first needed steps on the road to racial repair. While it has had its critics, acknowledgment of past wrongs to those who were harmed by them was a core component of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Accepting responsibility for harm that was caused is a necessary step in a reparation process by creating the space for the responsible party to admit wrongdoing, and the harmed party to have the choice to start a healing process.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Last year, the American Psychological Association apologized for its role in perpetuating systemic racism. “The American Psychological Association failed in its role leading the discipline of psychology, was complicit in contributing to systemic inequities, and hurt many through racism, racial discrimination, and denigration of people of color, thereby falling short on its mission to benefit society and improve lives,” the statement read.

A powerful acknowledgment not only addresses the historical ways in which harm was caused by the perpetrator, but it also offers an apology and accepts responsibility for the ways in which both the action and inaction of the perpetrator caused harm, which the APA statement goes on to do.

While apologies like these from medical associations and other institutions within the medical industry are important, without deep structural action in the form of redress, reckoning, and acknowledgment, these are just more empty words.

Increasing Black Wealth to Improve Black Health

In 2016, the typical white family had nearly ten times the amount of wealth of the average Black family. “Power, money, and access to resources—good housing, better education, fair wages, safe workplaces, clean air, drinkable water, and healthier food—translate into good health,” according to Harvard researchers.

Those who live in poverty have less access to healthcare, lack of healthy nutritional options, are more likely to be uninsured, face higher threats of eviction and homelessness, and are concentrated in jobs that since the onset of the pandemic have put them in positions more likely to contract COVID-19.

Since health outcomes are so inextricably linked to income and wealth, increased economic power by means of a reparations package that seeks to close the racial wealth gap would target the structural health issues that Black people face. Increased wealth for Black Americans would mean more discretionary income to devote resources to healthier food options, preventative health screenings, and mental wellness programs.

As noted by the Harvard researchers, efforts to provide better health care in a “population that lacks access to essential resources for health are bound to fall short.” Therefore, to address the structural inequity within the healthcare system, we must take an explicit racially conscious approach rather than a racially blind one.

Decolonization of the Medical Industry

From both a mental and physical health perspective, we must invest in and restructure the medical workforce. Studies have shown that sharing a racial identity with your doctor is associated with improved health outcomes. For example, a study in Florida that examined the racial relationship between doctors and the infants they cared for found that when Black doctors delivered Black babies, the infant mortality rate fell by 50 percent.

The prevalence of implicit bias, particularly in the medical field, has been well documented. Studies have shown that Black people, particularly men, are four to nine times more likely to be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia than white Americans, while also less likely to be diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder.

While Black Americans make up 13 percent of the US working-age population, they only comprise five percent of the healthcare workforce, even as surveys have shown that patients develop more trust and feel better understood by providers who look like them. Nonetheless, simply focusing on racially diversifying the medical industry alone will not address the deep inequities Black communities face.

Education experts, like Gloria Ladson Billings, have long called for large-scale investments to create more culturally competent K-12 pedagogy that seeks to affirm, appreciate, and correctly contextualize Black history and culture. This same framework must also be applied to the medical industry. There must be a deeper investment and commitment to address the various educational barriers at play to address these pipeline problems.

Turning Research into Action

Like wealth, trauma is not equally inherited in this country. In every historical period, Black Americans have faced racial violence and discrimination within every single US institution.

Research on this subject is plentiful. (I have included a list of resources at the bottom of this article). And there is more research that could be done to explore the intergenerational effects of trauma, particularly within the Black American community.

No single entity within the medical industry alone can repair the racial trauma that Black people carry today. A comprehensive national effort that reaches deep into states and cities across the country must be launched to address the multitude of economic, social, and psychological harm done to Black people. Considerable organizing will be required for the nation to take on this work. But while the task ahead remains challenging, the effort is essential to heal the trauma of our nation.

Currently, a bill in Congress would establish a Commission to study what reparations might look like across the country and within different contexts. This is important, but research is not enough. Research without real commitment and sustained action would only kick the can down the road.

Even in our sector, though, particularly amongst ivory-towered academic and philanthropic institutions, too often this research is devoid of real action and power building. As we continue our learning journey around reparations, it’s important that we utilize community-engaged methods to include the input and participation of those at the forefront of the issue. This will not only foster greater trust between grassroots organizations and those conducting research but also ensure that the programs and services are effectively empowering the community that researchers seek to serve.

Resources

- The New England Journal of Medicine: “Reparations as a Public Health Priority – A Strategy for Ending Black-White Health Disparities”

- American Psychological Association: The Legacy of Trauma

- Congressional Black Caucus Foundation: Black Health and Black Wealth: Understanding the Intricate Linkages between Income, Health, and Wealth for African Americans

- Frontiers in Public Health: “The Case for Health Reparations”

- Frontiers in Psychiatry: “Epigenetic Modifications in Stress Response Genes Associated with Childhood Trauma”

- NCOBRA: The Harm is To Our Genes

- Journal of Black Psychology: “Microaggressions and the Enduring Mental Health Disparity: Black Americans at Risk for Institutional Betrayal”

- American Educational Research Journal: “Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy”

- American Journal of Public Health: “Trauma-Informed Social Policy: A Conceptual Framework for Policy Analysis and Advocacy”

- Historica Canada: Intergenerational Trauma: Residential Schools

- Critical Philosophy of Race: “Inheriting Racist Disparities in Health”