Far too many people in the US, when thinking about climate change, engage in a general assessment that goes something like this:

- “Humans need to do something soon to prevent catastrophic climate change.”

- “And if we do what’s necessary, yay! We’ll have saved the planet.”

- “If we don’t, it’s going to be really bad, maybe irreversible.”

With worsening droughts, hurricanes, and fires already affecting us, it’s easy to think about climate change itself as a fire that just needs to be put out. There’s nothing obviously wrong about this win-or-lose way to think about greenhouse gas emissions and their impact. It follows a typical logical flow:

- Society has a problem →

- Problem requires solution →

- Whether society responds with necessary solution determines success or failure.

Indeed, this is how I first thought about it as well. When I first became curious about climate change roughly ten years ago, I began asking friends (and strangers) whether they thought we’d succeed as a species in addressing the problem. The responses were generally pessimistic, which came as a surprise to me, and ultimately led me to dedicate my career to advocating for a just and equitable energy transition.

When I started working with community-based organizations, they gave me hope. I also studied the issue more in law school, particularly with a justice-oriented lens. And that led me to where I am now: in my fifth year of advocating for renewable energy. And not just any kind of renewable energy, but community-owned renewable energy. Because only through energy democracy can we ensure that society’s response to transform our energy infrastructure will benefit everyone. And by “everyone,” I mean everyone, especially folks from marginalized communities.

But after years of organizing and studying and advocating, I’ve come to realize this “success or failure” framing is not just wrong—it’s dangerous.

Why we need to rethink success in dealing with climate change

Everyday people, at least in the US, are more concerned and more pessimistic about climate change. Perhaps this is because of diminishing trust in government or the sheer scale of the problem. From my experience, people who work on climate, energy, or social justice issues are a bit more hopeful than others, even if they are weighed down at times by worry. It appears that people around the globe are a little more optimistic that we can avoid the worst effects of climate change. But is that enough? Avoiding the worst effects?

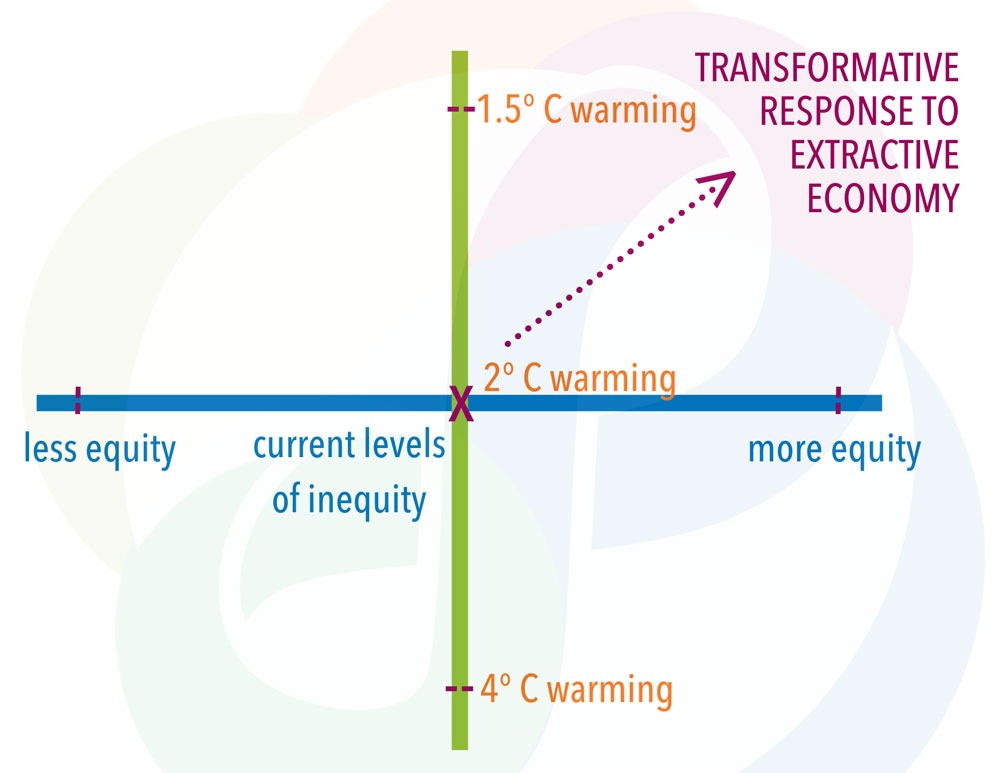

In this context, a pass/fail framing of climate change has two key problems. First, it doesn’t address the fact that how weakly or boldly we respond will affect how many lives and livelihoods are lost due to climate change. In other words, instead of a bright line pass/fail, there are shades of success and failure.

The Paris Agreement calls for limiting warming to well under two degrees Celsius and ideally under 1.5 degrees. This goal is a bright line of preventing only the worst impacts of climate change. But the bright line shouldn’t lead us to think about the crisis in black-and-white terms. Currently, our level of warming is roughly one degree Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Increasing that to 1.5 degrees of warming already represents terrible consequences. It will expose 350 million more people worldwide to severe drought. It would also expose 14 percent of the world population to severe heat waves. This suffering would be disproportionately borne by women, the poor, and people of color. So, it’s important to not think of even 1.5 degrees of warming as some ideal goal at which we’ve avoided significant problems.

Second, and perhaps most problematic, this black-and-white framing serves as a perfect foundation for indifference and inaction. If we think of the problem of global heating as something that we’ll either solve or not, it’s too easy to pass it off as a battle we will lose and therefore should not even bother to fight.

Success is a spectrum toward transformation

Messaging about climate change is difficult. So, of course, there’s value in simplifying messages by articulating clear goals and deadlines to explain what the world needs to do. “Keep global temperatures under 1.5°C of warming” and “achieve net zero emissions by 2050” are clear and simple goals.

But it’s dangerous to simplify the task of combating climate change. We risk missing the core problem. For years now, the climate justice movement has been drawing more and more attention to the interconnection between ecological degradation and social inequity through the Just Transition Framework.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The problem of greenhouse gases is not an isolated problem, but one interconnected with our economic systems. These systems have allowed the mostly unchecked extraction of natural resources, pollution, and exploitation of human labor, lives, and livelihoods, particularly from the poor, Indigenous, and people of color. To fully address climate change, we not only have to limit warming on the planet, but we have to do it in a way that unravels the current exploitative and extractive economic system. Success should thus be measured by our progress on a spectrum toward a truly transformative solution to these intertwined problems.

When we unpack the root causes of climate change and inequity, we frame a more evidence-based solution—what the Just Transition Framework refers to as a “regenerative economy.” A regenerative economy includes all sectors of the economy, such as transportation and food, in addition to energy. For each of these sectors, we must consider how that sector must change as a part of a just transition. Let’s take a closer look at a just transition in the energy sector.

One trillion dollars of new energy economy wealth, and it goes to…

Not only is transforming the energy system a crucial part of addressing climate change, revamping the sector has the potential to touch everyone’s lives. That’s why it’s so important to shift away from thinking about climate change solely in terms of whether we’ll limit warming to a certain level or not. From the lights we turn on each day, to the tractors that help farm our food, everything uses energy. The system is so vast that according to one study, transitioning to 100 percent renewable energy globally would require an investment of $73 trillion.

Sounds like a lot, right? But that study also finds that such a transition would pay for itself in seven years and create 28.6 million more full-time jobs. And get this: globally, shifting to renewables promises roughly a trillion dollars in new wealth generation!

Let’s pause to think about that for a moment. Who’s going to gain all of this wealth? With ever-worsening wealth inequality, is it even a good thing? How do we make sure everyone sees a piece of renewable energy gains? How do we ensure that those who need it the most receive at least a substantial portion of this new wealth?

We need to equitably democratize the energy sector and promote community governance so that all communities benefit from the massive new infrastructure build-out. But as this new energy economy is getting off the ground, there are signs that the transition isn’t benefiting everyone equally, with evidence of both racial and economic disparities.

In other words, a shift to a just energy system won’t just happen automatically, particularly for disenfranchised communities. We must intentionally and earnestly intervene to ensure that the energy transition robustly benefits marginalized communities.

That’s because the system has baked into it many barriers that make it hard for communities to democratically manage energy generation that serves everyone. For instance, most states don’t have laws that enable neighbors to pool their resources together to start a community solar garden in their neighborhood that can be collectively owned and that can provide energy to multiple households. And while some homeowners can own solar panels on their rooftops, about half of households cannot, for reasons that include being renters or not having enough money to cover the upfront costs.

By researching, innovating, and advocating for change, we can overcome these barriers. After navigating the various legal issues around community-owned energy, the Sustainable Economies Law Center, the nonprofit where I work, has partnered with community members and participated in a cleantech business accelerator program to help form the People Power Solar Cooperative. In March 2019, the co-op launched the first known cooperatively owned residential solar system in California. The co-op is now assisting communities in developing additional grassroots-led and community-based solar projects around the San Francisco Bay Area. And folks elsewhere in the country, like a nonprofit in Cleveland, Ohio known as Cleveland Owns, have begun to replicate the model.

At the same time as we work locally, we need major structural change across the country in order to further a transformative energy vision. That’s why I’ve collaborated with two leading energy equity attorneys to found the Initiative for Energy Justice. We created the Initiative after recognizing the gap in support for frontline communities and equity advocates in energy policy-making arenas. The Initiative provides law and policy resources (see the new Energy Justice Workbook) to advocates and policymakers to advance local and state shifts to equitable renewable energy. The considerable response and requests for this type of work has been humbling and heartening.

Nationally, our thinking on climate change is starting to change. And that’s a good sign. The decades of work by environmental and climate justice advocates has fundamentally reshaped the narrative. And the recent explosion of youth activism has heeded the justice-centered message more than their elders. There is now a growing public focus on the broader social benefits from an energy transition, such as equitable wealth-building opportunities, good jobs, and health improvements. And this demand for a Green New Deal is in turn increasing the political will to act.

It’s a change that has stirred in me profound hope over the past year. Because beyond whether we achieve everything advocates envision for a Green New Deal or not, it is inspiring to see that our nation’s young people do not view climate change as a pass/fail test. For them, failure is not an option. Instead, they pose a different question: how transformative will our success be?