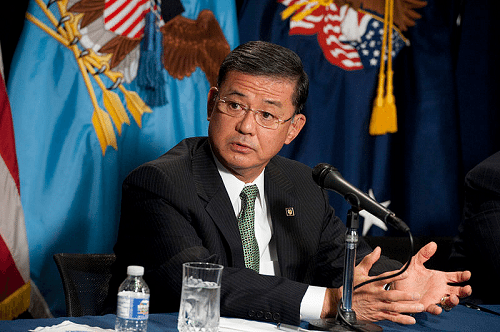

Amidst standing ovations he received from the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, Eric Shinseki made some astounding statements about his review of the burgeoning scandal regarding VA hospital appointments—and they weren’t his apologies to veterans, Congress, and the public. They were statements reflecting a cabinet officer who seemed out of his element, in a job in which he failed—not to remake a long troubled system, but to even recognize the extent of the problems.

Shinseki sounded all muscular, hardly ready to turn in his resignation to the president, whom he was scheduled to meet with only a couple of hours later. But earlier in the day, the cards were on the table. Representative Tammy Duckworth (D-IL), herself a wounded veteran and often seen as a bellwether for President Obama’s opinions on veterans issues, called for Shinseki to resign. If Shinseki was on a short leash for the last month or so, Duckworth’s statement announced that Shinseki’s time was up.

The president met with Shinseki, and Shinseki offered his resignation. They met at 10:30 on Friday; after meeting with Shinseki, Cabinet Secretary Rob Nabors, and Deputy VA Secretary Sloan Gibson, the president announced that he accepted Shinseki’s resignation at 11:15 and suggested that it was Shinseki’s judgment that he would be a distraction going forward were he to stay in office.

As we have stated previously, while Shinseki was likely to be gone sooner or later in the hospital wait time scandal, the problem goes much deeper than the man himself. It reflects dynamics with the White House, within the VA, and with Congress

Inside the VA: The president said that Shinseki was disappointed that “bad news did not get to him.” In his morning speech at the National Coalition, Shinseki expressed shock that he was lied to by subordinates about the existence and extent of the waitlist problem. “I cannot explain the lack of integrity among some of the leaders of our healthcare facilities,” he said. “This is something I rarely encountered during 38 years in uniform. And so I will not defend it, because it is indefensible, but I can take responsibility for it and I do.”

Contrary to the President’s and General Shinseki’s concerns, the bad news has been public for a decade, through 18 Inspector General reports and confirmed by other analyses such as the General Accounting Office’s 2013 report. If they weren’t reading the reports from the OIG, Shinseki could have looked at the CNN truck camped outside his office since November with investigative reporter Drew Griffin providing breaking news about the Phoenix VA hospital’s fraudulent waiting lists.

As Shinseki hit the bricks, both he and the president cited the numerous accomplishments of the administration on a number of veterans issues, including a reduction in veterans homelessness. But the core mission of the VA is that it is a healthcare delivery system. For a decade, report after report was telling Shinseki, his subordinates, and his predecessors exactly what was going on. Claiming that they didn’t know because subordinates lied to them doesn’t wash.

Moreover, in our society’s rush to manage by stretch targets such as promising veterans waits of no longer than 14 days for hospital treatment, the incentive for VA managers is to somehow meet the target. Solving the problem falls by the wayside so long as staff can find ways of fudging the books to show that the goal was met—and that managers could get their bonuses. The culture of the VA is hidebound, overly bureaucratic, stuck with viewing problems through the limited, distorting prisms of specific programs and targets. General Shinseki might have been a fine military commander (especially if it is true that he never had subordinates lie to him in the way his subordinates at the VA appear to have routinely dissembled), but he fell short as a leader of a national healthcare system—which is what the VA is.

Inside the administration: All those IG and GAO reports went to the White House too—not just the Obama White House, but to the Bush administration as well. It is clear that both administrations fell horrendously short of competently preparing for the return of demobilized veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. Diehard defenders of both administrations point to budget cuts in the VA, presuming that Congress had cut the VA like all others, but those budget simply cuts don’t exist. The VA has constantly had budget increases while other federal agencies have found themselves slashed and eviscerated, with annual increases that have actually speeded up in recent years:

Total VA Budget by Fiscal Year

$12006 $73.1b

$12007 $81.8b

$12008 $91.0b

$12009 $97.7b

$12010 $127.2b

$12011 $125.2b

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

$12012 $126.8b

$12013 $139.1b

$12014 $153.8b

$12015 $163.9b

With increasing budgets, the VA had resources to try to resolve some dimensions of the crucial problems in its core medical delivery and benefit functions, but even with a reduction in the benefits backlog, the results are still far from acceptable, made worse by the current albeit longstanding hospital wait-time scandal. The White House has a number of offices and functions—including Rob Nabors, the Cabinet Secretary—who are in positions to spot ten years of IG reports and numerous others to call cabinet secretaries like Shinseki to the White House to demand explanations and action.

In this instance, the VA scandal is one of managerial shortcomings within the VA itself, but also within the White House’s oversight of the second largest agency of the executive branch. If Shinseki is taking responsibility, the responsibility ought to be shared by others in the White House.

Inside Congress: When the IG reports first were issued about the VA hospital crisis that exists today, President Obama was Senator Obama and a member of the Senate committee charged with oversight of veterans issues. In the intervening years, the IG and GAO reports have been given to Congress and to members of the House and Senate committees concerned with the VA. Is it possible that the dozens and dozens of members of Congress and their staff members simply failed to look at these reports, to notice their titles, to glance through the executive summaries—until they were somehow shocked to learn about the deaths alleged to have occurred while veterans waited for appointments in Phoenix?

What a dereliction of legislative branch oversight of the executive branch of government! The response of the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America to Senator Richard Burr’s (R-NC) denunciation of veterans’ service organizations for being in bed with Shinseki and the VA summarizes the performance or lack of performance of Congress for veterans:

“Unfortunately, when we have come to Congress for help, all too often we have been let down by Washington politicians. We have been especially disappointed by the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee, which amazingly, still lacks a single member who is a combat veteran. If the committee was made up of at least a few veterans, we have no doubt you and the Committee would be more aggressive, more effective, and more connected to the veterans community. But since you are not, we expect you to listen that much more and work that much harder.

“Thus far, this Senate has failed to live up to its promise to veterans. Instead, political stunts and obstructionism have supplanted the duty that you and others in the Senate have to our nations’ veterans. It is also now painfully clear to all Americans that you and Senate leaders (of both parties) have not effectively exercised your oversight responsibility or passed needed legislation.”

Where to go next: Shinseki’s temporary replacement is the Assistant Secretary of the VA, Sloan Gibson, who was formerly the executive director of the USO, the Congressionally-chartered nonprofit that runs 150 or so USO centers across the globe to boost the morale of transitioning and deployed troops wherever they may be stationed. It was clear in the president’s statement that he will be recruiting a new VA secretary, and it didn’t sound like it was Gibson, for whatever the reason might be. The result is that Gibson is in a great position to do something radical about the systemic problem of the VA, to change its hidebound, bureaucratic culture from filling out forms in triplicate to solving problems.

There’s no secret that, among the 40,000 nonprofits nominally focused on veterans and the others that also serve significant veterans populations, there are a number of organizations doing little of much utility. There are others that punch way above their way, especially those veterans’ nonprofits that represent and serve post-9/11 veterans, who are returning to stateside to a dysfunctional VA bureaucracy that hadn’t done much to plan for their needs and numbers.

Many things can be done to correct the specific problems associated with the fraudulent waitlists, and even Shinseki announced some worthwhile initiatives—such as firing the managers in charge—during his speech to the homeless veterans group. But to get at the systemic problems of the VA, it’s time for the VA to give more than lip service to public private partnerships. It should be convening the many competent and impressive veterans’ organizations, particularly those with post-9/11 veteran constituencies who sometimes return home with a variety of hidden disabilities such as PTSD, and begin a thorough diagnosis and overhaul of the system to identify and eradicate the stultifying culture that infects so many parts of the agency.

It’s time for the young, energetic military groups to stand up and help the VA enter the 21st century. The VA has been making some strides—under Shinseki—to work better with nonprofits, including through programs such as the Supportive Services for Veterans Families (SSVF) grant program, drawing on nonprofit energies, talents, and commitments. For however long Gibson remains at the helm of the VA, he should harken back to his nonprofit identity as the former CEO of the USO and turn to the nonprofit sector to breathe life back into this crucial agency. Veterans deserve nothing less from the VA—and from the 40,000-plus nonprofits that say they exist to serve veterans.—Rick Cohen