Nationwide, the past year and a half has been marked by both COVID-19 and a rising movement against anti-Black racism. Both have driven home the dire need to advance equity. In western Massachusetts, the Community Foundation of Western Massachusetts (CFWM) affirmed our commitment to racial justice work and set out with new resolve, only to be confronted (yet again) by the vast scope and scale of the challenges.

No single sector can advance and sustain equitable change on its own, be it government, nonprofits and philanthropy, or business. Worse, each has too often contributed to the opposite—namely, inequity. These problems are compounded by vast regional inequality. In philanthropy, for example, one study found that per-capita philanthropy in the Mississippi Delta was 40 times less than in New York City ($41 per capita versus $1,966).

Systemic change requires patient capital, creativity, and commitment. Philanthropic dollars may be less scarce in western Massachusetts than the Delta. But they are a good deal less plentiful than in Boston or New York City. To act effectively, we’ve had to combine our local knowledge and networks with external resources. During COVID-19, such partnerships changed from being “nice to have” to “must haves.”

Some background: Since 2013, I have led CFWM, a medium-sized community foundation that serves about 700,000 people living in 69 cities and towns, including the state’s third-largest city and its most rural county. The foundation has $200 million in assets and in 2019 invested over $10 million in grants, scholarships, and interest-free loans across our region ($20 million in 2020). These resources are significant, but pale when compared to our neighbor, The Boston Foundation, which has $1.3 billion in assets and distributed $126 million in grants in 2019 ($215 million in 2020).

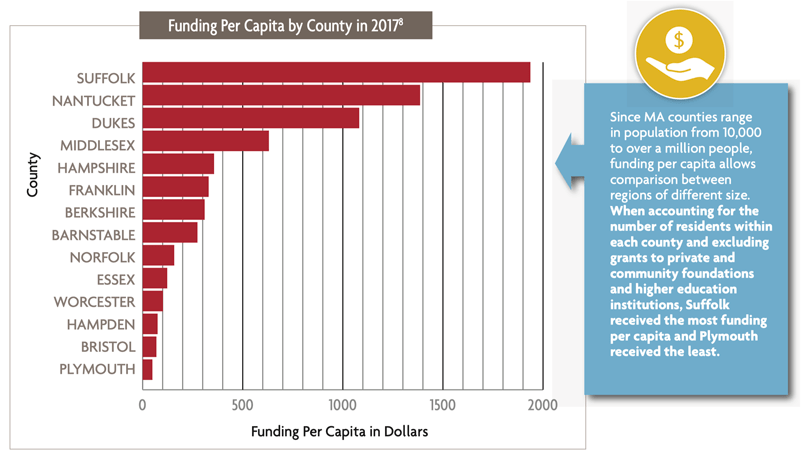

According to Philanthropy Massachusetts’ Giving Massachusetts report, excluding grants to private and community foundations and higher education institutions, Hampden County, one of the three counties we serve, received less than $100 per capita in funding, compared to $1,900 per capita in Boston’s Suffolk County.

Turns out the health disparities, educational outcomes, and poverty rates are quite similar in metro Boston and Springfield, and philanthropic dollars per capita are 19 times, or 1,800 percent greater, in Boston to help address those challenges. Yes, the cost of living is 20 percent higher in Boston; still, the resources are vastly unequal. Traditionally, money that is made in and around Boston stays in and around Boston.

Our situation is hardly unique. Surely many small-to-medium sized cities, towns, and rural communities have similar stories to tell. But how can one address this mismatch?

Building equitable communities requires changing hearts and minds as well as systems that have perpetuated harms over hundreds of years. That means we need more effective ways to connect larger funders to those with lived experience, hyper-local networks, and grassroots advocacy expertise to work together to shape the solutions.

This is easier said than done. First, smaller organizations often face major resource constraints. To connect local knowledge with external groups requires trusted partnerships. A second complication is that often those potential external partners are the very institutions that help create or maintain the inequity in the first place.

Therein lies the rub—the great mismatch in size, culture, systems, and trust. How does a $2 billion philanthropic organization—or the federal government—share power and work with a whole host of smaller partners immersed in communities? How do they connect with the organizations that are critical witnesses of and responders to emerging needs, and whose priorities and operations may be totally different?

One response is to shift resources to groups with Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) leaders. Investing greater dollars into BIPOC communities, businesses, and nonprofits is a great first step. And while many are heading in that direction, including CFWM, some are realizing that implementation can generate unintended challenges for smaller organizations, like an IRS snafu called “tipping,” where a large contribution from a single donor to a 501c3 public charity causes that organization to fail the IRS public support test and is therefore “tipped” out of public charity status, or complex reporting requirements that handcuff small businesses or community agencies.

Community foundations bring a unique set of tools for this work. We focus on a specific geography and, if we do our work well, we are embedded in our communities, listening and responding. We can usually accept large contributions without affecting our public support test, unlike smaller community-based organizations. We can then move those dollars from the larger contributor into the community to be used by those with local expertise and trusted networks that can shape solutions that specifically address local needs. We can accept non-cash assets like real estate and shares in a family business and turn them into grants and scholarships. We do complicated fund accounting and can bear the reporting brunt.

Here at CFWM, we are actively exploring new models and learning from groups like the Association of Black Foundation Executives, PEAK Grantmaking, and the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, all of which have long advocated for grantmaking equity. Many colleagues across the country have been testing new models and practices. We also learn from other community foundations in small cities or rural regions, who, like ourselves, struggle with resource constraints.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While we are still learning ourselves, I want to share three recent partnerships that might provide some clues regarding how smaller foundations might work with more resource-rich external partners to both secure resources and advance equity. One of these launched in 2018 and two in 2020—the first, with a $2 billion private foundation; the second, with a small network of private foundations joined by thousands of donors; and the third, a direct partnership with the state government. In each case, partnerships allowed for more resources to reach our community in support of equity goals. Of course, each partnership had its own unique features and complexities. Navigating those complexities is a critical part of philanthropic equity work.

A Private Foundation Partnership

Three years ago, the Barr Foundation sought to expand its arts programming beyond Boston to reach the entire state and turned to five community foundations to do so. Barr recognized that these foundations could help the state’s creative sector become more equitable and enduring. Barr began by providing a planning grant to learn more, develop trust, and co-create a model with these five foundations.

Barr’s initial three-year commitment evolved into a 10-year partnership that comprises cohort learning, data and research, convening, planning, grantmaking, measurement, and evaluation—all of which expand the capacity of the foundations to be stronger, more effective community leaders. Barr has amplified access to capital, expertise, data, and learning while community foundations have brought forward their local expertise, trusted relationships, and ear-to-the ground knowledge. As partners, we need each other to inform our work, to create greater impact, and measure change.

The key learning from this partnership so far is that to work effectively and equitably, the partners must start with an intentional focus on developing trust and shifting any power imbalances, real or perceived. We worked at that by planning together, co-creating the program, and by building in regular opportunities for learning and reflection. This required investing more time than initially imagined, more resources devoted to communication and convening, and a shared commitment to learning.

Partnerships in Collaboration with Community and Private Foundations

When our world turned upside down in March 2020, the Boston area witnessed an outpouring of philanthropic support. A small group of private foundations observed many other areas of the Commonwealth hit equally hard by the virus lacked access to that scale of giving. One8 Foundation, a private family foundation, took the lead and partnered with Lauren Baker, the first lady of Massachusetts, to raise money to support communities in the rest of the state. That led foundations and more than 17,000 individuals to pool resources and create the Massachusetts COVID-19 Relief Fund. That effort provided $32.2 million to communities with fewer philanthropic resources to lean on.

To deploy those dollars effectively, the Massachusetts COVID-19 Relief Fund turned to the community foundations across the state. In a radical shift in emergency fundraising, the Relief Fund recognized the unique position and role of community foundations to distribute philanthropic dollars quickly to where they were needed most.

CFWM received large grants every three weeks from the Relief Fund, which were redistributed the same week to food providers, healthcare organizations, shelters, senior programs, and others responding to the crisis in every corner of our region. We employed an equity lens in doing so, which would have been hard for the Relief Fund to have done well directly. We received calls, email, and notes from community-based organizations expressing their appreciation for the speed, streamlined process, and lean reporting requirements, all of which reinforced trust.

Partnering with State Government

The Massachusetts legislature took notice of the Relief Fund partnership. It saw larger funders connecting with local expertise and trusted networks via community foundations providing locally informed, streamlined, and accountable fund distribution processes. When the legislature realized that many residents were unable to access federal CARES Act relief funds, it allocated $15 million and turned to 14 community foundations to quickly distribute those dollars. The funding went to support immigrants who often had no or limited access to federal relief. This initial partnership is leading to another, with community foundations statewide working with the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development to distribute over $30 million in federal funds to support people who are food insecure.

State governments and hyper-local community-based organizations have distinct characteristics and behaviors. If state governments only work with larger, more well-resourced organizations because they work in similar ways, then inequity will persist. So, communities must find ways to close gaps and advance equity. This will require concessions and compromise. There were numerous conversations between the state and community foundations to finalize process and reporting rules. Each had to give up something. Making these partnerships last will require fundamental power shifts in how state government works with philanthropy, which may be difficult to achieve when not in a state of emergency.

Emerging Lessons

Each of these partnerships had an external funder (private foundation, pooled emergency fund, or state government) with significant resources but without the local expertise to effectively disburse funds. Meanwhile, the local on-the-ground agencies and organizations had the community knowledge but not the resources. This partnering is nascent for us and not perfect, yet we are learning how it can help create a more equitable system for distributing community support.

We are learning the cost of cultivating this kind of partnership as well. Staff cannot magically expand their capacity to carry out all the communications, data collection, and reporting such partnerships require. Amid COVID, we had to bring on additional communications experts and a contracted program manager. Most small-to-medium sized community foundations pairing up with government and other large funders will likewise need increased capacity for data collection, analysis, and reporting. For CFWM, we also needed to increase our skills, knowledge, and abilities around intercultural competence, inclusion, interrupting racism, managing conflict, and culture change. To accommodate more partnership opportunities in the future, CFWM will need to add additional staff resources to support accounting, data collection, and reporting.

A similar logic applies within our communities. At CFWM, we recognize that many smaller groups—especially in Black and Indigenous communities and communities of color—don’t yet have the staffing resources to respond to a federal proposal or collect and manage the data for complex reporting. Partnering to build this capacity is a critical part of equity work. Looking anew outside of our sector—coupled with testing, learning, and sharing—will help us to better respond.

Even with the cost of additional skill development and capacity, these three partnerships demonstrated a much more efficient and more equitable way to drive more funding to community-based organizations. It’s clear that local nonprofits and residents better understand the issues in their communities and therefore can more creatively and effectively respond. And what these experiences also taught us is that it’s not simply about more money getting to these local organizations. It’s about repairing inequity, building trust, strengthening capacity, and creating the partnerships that will produce meaningful progress in and beyond an emergency.