August 27, 2018; Chronicle for Higher Education and New York Times

Student loan debt has become a profit center for universities, a significant obstacle to the upward mobility of younger low- and moderate-income people, and a growing drag on housing-related sectors of the economy. That’s the emerging conclusion from a look at statistics from several sources, and it’s why Seth Frotman, student loan ombudsman for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), announced he will resign from his post in protest September 1st. His cited reason? “The [CFPB] has abandoned the very consumers it is tasked by Congress with protecting. Instead, [it is] serving the wishes of the most powerful financial companies in America.”

According to the Federal Student Aid office, the typical student borrower obtains a loan of $6,600 a year, averaging a cumulative $22,000 by graduation. Of borrowers who started repaying in 2012, just over 10 percent had defaulted on their loans three years later. But over the following two years, the number of defaults increased to 16 percent—totaling more than 841,000. Nearly as many were severely delinquent. Collectively, these borrowers owed more than $23 billion, with more than $9 billion in default.

“Nationally, those are crisis-level results, and they reveal how colleges are benefiting from billions in financial aid while students are left with debt they cannot repay,” wrote Ben Miller, senior director for postsecondary education for the Center for American Progress, in a New York Times commentary.

According to Miller, one common tactic of colleges that gets borrowers into trouble is to encourage them to defer their repayments until a later date. This works for the colleges, who are evaluated on the percentage of students who default in the first three years after graduates, but often fails the students.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Federal law requires all colleges participating in the student loan program to keep their share of borrowers who default below 30 percent for three consecutive years, or at no more than 40 percent in any single year. However, Miller cited an analysis showing that five years after loans were issued in 2012, 636 schools reported high default rates, with for-profit institutions having a particularly egregious record. Forty-four percent of borrowers at for-profit schools faced some type of loan distress, including 25 percent who defaulted. In fact, most students who defaulted between three and five years into repayment attended a for-profit college.

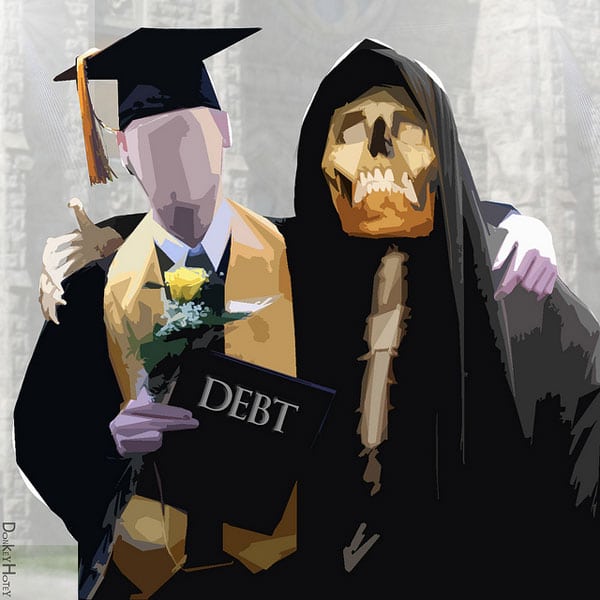

More broadly, the overall dynamic has been to push many students who should be receiving grant aid to attend college to instead become overextended by debt. As Miller wrote in his op-ed, “Too many borrowers and defaulters are low-income students, the very people who would receive only grant aid under a rational system for college financing. Forcing these students to borrow has turned one of America’s best investments in socioeconomic mobility—college—into a debt trap for far too many.”

Evidence that this “debt trap” is having significant impact is offered by a new study published in the journal Demography. It shows a correlation between college attendance and rising foreclosure rates. The study, which looks at annual changes in college attendance and home foreclosures in 305 American metro areas (covering as much as 85 percent of the US population), finds that nationwide, a one percent increase in college attendance is associated with 11,200–27,400 additional foreclosures. The research demonstrates the extent to which rising college tuition—and the resulting loans—are a burden on American families and have serious implications for housing stability and economic mobility.

According to NPR, the CFPB has handled more than 60,000 student loan complaints since 2011 and returned more than $750 million to aggrieved borrowers. However, over the past year, the Trump administration has increasingly marginalized Frotman’s office. For example, in December, the Department of Education announced cuts to debt relief for students who claim they were defrauded by their colleges. Last August, the US Department of Education announced it would stop sharing student-loan information with the bureau. And earlier this month, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos took steps to scrap a rule designed to punish schools where graduates struggle with deep debt.

“American families need an independent consumer bureau to look out for them when lenders push products they know cannot be repaid, when banks and debt collectors conspire to abuse the courts and force families out of their homes, and when student loan companies are allowed to drive millions of Americans to financial ruin with impunity,” wrote Frotman in his resignation letter.—Pam Bailey