Just hours after Donald Trump was declared the winner of the 2016 presidential election, the search for the reasons we were so surprised was well underway. What forces were at work in our society that had gone so unnoticed that the results were so surprising? Attention quickly fell upon the angst of white, working-class voters who felt left behind and left out. Five months of research into the 2016 election leads to a more nuanced and disturbing understanding: Worker disenfranchisement was a factor, but less important than the growing racial animosity among those white voters.

The American National Election Study has been conducted following every presidential election since 1948. According Ohio State Political Science Professor Thomas Wood, ANES provides an “incredibly rich, publicly funded data source [that] allows us to put elections into historical perspective, examining how much each factor affected the vote in 2016 compared with other recent elections.” Its 80-minute interviews gather information about attitudes and motivations that might otherwise not be available and allow the study to go much deeper than the typical exit poll.

Writing in the Washington Post, Professor Wood shares his take on the ANES dataset in an attempt to better understand underlying cultural forces at play. White working-class voters, especially those in areas hit hard by plant and mine closings, were the wildcard that put enough Electoral College votes in the Trump column to elect him. What motivated them to make that choice? While economics and the growing appeal of authoritarian, “alt-right” ideology played some part, the key factor, the one that makes this election different than others, appears to have been their racial bias.

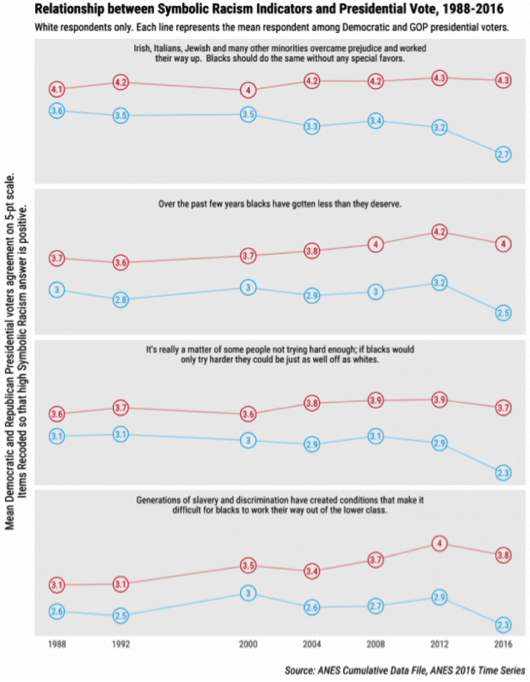

Comparing the attitudes of white Democratic voters with their Republican counterparts, Professor Wood found that “Since 1988, we’ve never seen such a clear correspondence between vote choice and racial perceptions. The biggest movement was among those who voted for the Democrat, who were far less likely to agree with attitudes coded as more racially biased.”

Democrats seem to have taken the path toward a more racially inclusive culture; those more motivated by their fear of others vote the other way. This jibes with earlier data gathered during the primary campaigns, which Jason McDaniel and Sean McElwee looked at when writing for Salon.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

On just about every measure, support for Trump increased along with measured racial animus…increased levels of overt racial stereotyping among white respondents—as measured by belief that black people, Muslims, and Hispanics are “lazy” or “violent”—strongly increases support for Trump, even after controlling for other factors.

While the strength and authoritarian persona of President Trump had some appeal, both factors were overshadowed in the end.

“Finally, the statistical tool of regression can tease apart which had more influence on the 2016 vote: authoritarianism or symbolic racism, after controlling for education, race, ideology, and age. Moving from the 50th to the 75th percentile in the authoritarian scale made someone about three percent more likely to vote for Trump. The same jump on the SRS scale made someone 20 percent more likely to vote for Trump. Racial attitudes made a bigger difference in electing Trump than authoritarianism.”

Three other researchers, John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck, just published their conclusions about this election in an article in the Journal of Democracy. They too saw growing racism among the key drivers of the Trump victory: “Three factors…help explain this outcome. First, fundamental economic and political trends favored a Democratic popular vote win. Second, the party coalitions had become more polarized by race and education during Obama’s presidency. Third, Trump’s focus on issues connected to ethnic and social identities made attitudes toward immigration and African Americans more important in voters’ choices in 2016 than they had been in 2012.”

The president’s victory came with a very narrow margin, and the new administration’s first days have been rocky and protest-filled. What we now see is that racism and bias remain key motivators for a significant part of the American population. None of us—politicians, policymakers, anyone concerned about solving the critical human problems we face—can ignore this. Focusing on policy and legislation without directly confronting racial anger and hatred cannot change the landscape.—Martin Levine