November 5, 2018; New York Times

Today is Election Day in the United States of America. In a democracy, it’s critical that people vote, making their voices heard. Mostly, when we think of elections, we think of selecting a candidate who is running for office, such as the state legislature. In that case, we are voting to have someone represent us in government as public sector decisions are made. We empower others to make decisions on our behalf.

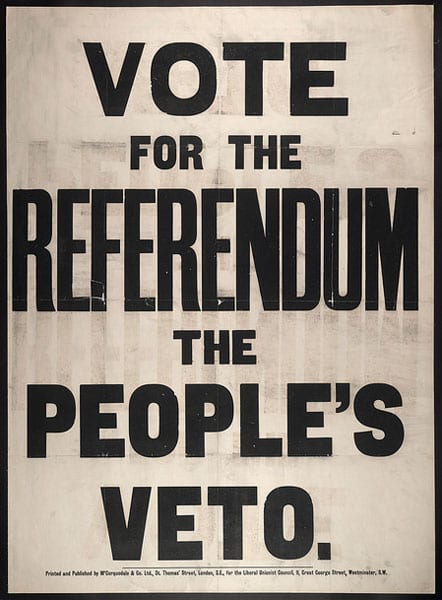

During this election, in at least 37 states, there will also be statewide measures put before the voters. With these referendums, voters get to directly voice their opinions on policies, many of which would be mandatory and become law if they receive a majority of the votes. The elected officials are not making the decisions; the voters are.

This kind of direct voting is very appealing, but it’s also an imperfect instrument. After all, one reason we elect representatives is for their judgment and discernment. In a well-functioning system—not that anyone could reasonably claim that we have such a system right now—representatives can hammer out compromises and deliberate with each other. Hard to do that on a yes/no ballot question.

In an opinion piece in the New York Times, Miriam Pawel goes through the history of ballot measures. Direct voting on ballot measures was introduced in the US in the 1890s, but few states have been as active with it as California. In 1911, California Governor Hiram Johnson advocated for voters to have the right to circulate petitions and put measures to a statewide direct vote as a way to circumvent corporate monopolies like the Southern Pacific railroad. In his inaugural address, he said that initiatives and referendums are not a cure-all, but “they do give to the electorate the power of action when desired, and they do place in the hands of the people the means by which they may protect themselves.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A recent example of this use occurred in 2016 when voters in San Francisco successfully put on the ballot and voted for a referendum requiring a tax on the sale of sugary sodas and similar products. This is something that the beverage industry had successfully fought against for years in state and local legislative bodies, but in San Francisco, residents, by organizing a petition drive and voting for the measure, were able to get around the blocks that the beverage industry constructed.

But two can play at this game. Earlier this year, the beverage industry spent $7 million to collect signatures and qualified for the fall 2018 ballot a measure that would have required a two-thirds vote for any tax votes statewide. The state legislature, to avoid the risk of a “yes” vote, voted to ban soda taxes statewide until 2030 in exchange for which petition sponsors agreed to remove the initiative from the ballot.

John Matsusaka of the University of Southern California contends that sometimes deliberation among representatives is a better path to collective decision-making than direct yes/no votes. The 2016 “Brexit” vote in Great Britain to leave the European Union put a complicated question on the ballot. But there was no room in a yes/no vote for the shades of gray that reflected the actual opinions of many Britons.

Today, there are 158 propositions on ballots being put before voters across the country. A list of them can be found here. They range from multistate issues like the legalization of marijuana, to the protection of salmon habitats in Alaska and allowing optometrists to practice in retail stores in Oklahoma on the more local level. Some are critically important, and others seem less so.

In his final State of the Union speech in 2016, President Obama said that “democracy breaks down when the average person feels their voice doesn’t matter; that the system is rigged in favor of the rich or the powerful or some narrow interest.” But, as President Obama also said in that speech, our brand of democracy is hard. What we learn from the pieces by Pawel and Matsusaka is the importance of doing that hard work by being informed and speaking up in the form of a vote.—Rob Meiksins and Steve Dubb