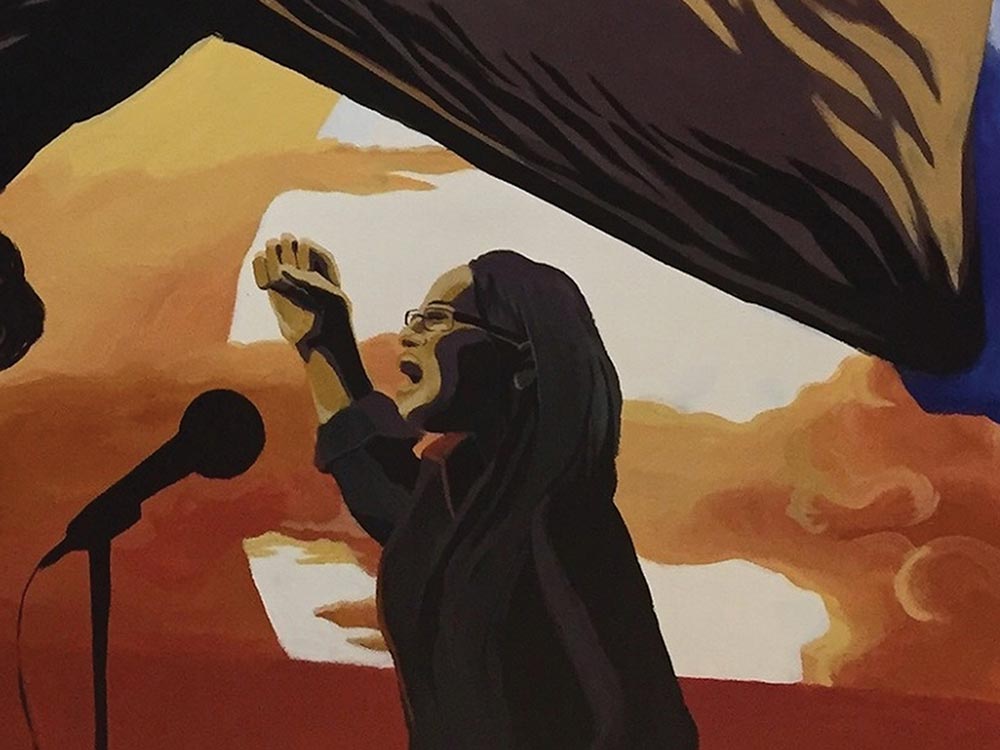

Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

This article is from the Fall 2021 issue of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Climate Justice: A Movement for Life.”

In this conversation about Puerto Rico, climate crisis, leadership, and the all-too-often unrecognized and unsupported knowledge of communities of color, Nonprofit Quarterly’s president and editor in chief, Cyndi Suarez, talks with a highly respected and beloved environmental leader in Puerto Rico who, because of the communications policy of the foundation he works for, cannot speak on the record.

Cyndi Suarez: It’s wonderful to connect with you! At NPQ, we are prioritizing four areas: racial justice, economic justice, climate justice, and health justice—because these are the major movements. This issue of the magazine is on climate justice—and because I’m Puerto Rican, and because Puerto Rico has played such a big role in this area, I wanted to circle back and see what’s going on there, and what the take on climate justice is right now. I remember that when I spoke to you back in 2017, you were saying that in Puerto Rico, people didn’t really believe in climate change. And I’m wondering what it’s like now. I know that so much has happened since COVID, and after Maria. A lot of movements were happening when I last spoke with you, and I would love some stories about what’s going on now with that.

Anonymous: I could connect you with some good community folks that could speak on the issue and really tell you, from the perspective of the communities, how they’re seeing it, how it’s affecting them. I’m sure you’ve seen that the Texas company Luma has taken over the electric grid. The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) no longer controls it.

CS: Since when?

Anon: It started about mid-last year. And then they pushed out the union. It’s been a big mess. Yet you still drive down the road and see electric pole after electric pole after electric pole that’s literally bent over and about to fall. You know, if this was in the U.S., we would be raising flags, because we wouldn’t be driving under those electric poles, because we’d be fearing that they would fall on us.

CS: It was like that when I went there. I thought to myself, “Isn’t that dangerous?”

Anon: Yeah! And, you know, we have a hurricane that’s coming. It’s currently a thunderstorm—it could become a hurricane. Maybe level one, maybe level two. It could be coming by as early as tomorrow night. And things like that mean that the country is still fragile? Economically, we know we’re fragile. And then, given the state of COVID . . . a lot of people have lost their jobs, a lot of people are still trying to get back on their feet. A lot of people still don’t have their homes in the best of shape, post-Maria. And so there’s still a lot of blue tarps on roofs. And you think about all of that, and you think about the fact that something like a hurricane one, or a hurricane two, could do a lot more damage than that hurricane five did when we were much stronger. We were in an economic crisis, but we hadn’t gone through COVID-19 and lived all the economic difficulties that it has caused, including the many people who died, the many households that were shrunk, right? Both here and in the U.S. But there are great folks that I can connect you with to get the full picture.

CS: I’ve been wanting to catch up and figure out what Puerto Rico is learning. Because, you know, that report came out today—the United Nations report.1

Anon: I saw that. Alarming.

CS: There’s just a lot to really put into perspective—because when I came into this position, what I learned from my time before, talking to people in the field, is that people don’t always have all the information of the ecosystem that they’re a part of. So, I’m hiring editors and bringing in art and bringing in all these different aspects and voices of the people that are doing this work.

Anon: Right. And that’s important.

CS: Most of the knowledge in our sector—99 percent of it, 98 percent of it—is aimed at funders. It’s not aimed at the people. The funders spend money to talk to other funders, because they think that’s the most important thing to do. So, you don’t hear from people like you. There’s so much happening that I hear about from people who call me, and I’m thinking, “There are so many solutions! There are so many things that no one’s covering!” So, I’m growing this journal as a multimedia platform. We have podcasts, we have webinars, we have fellowships, and we’ve been developing a program called the Voice Lab, which is for leaders of color to come in and be supported for a year to develop a portfolio of thought pieces, as a group. We’ve been doing a lot to highlight those voices, because honestly, what people like you guys know is very different from what is recorded as knowledge right now in the sector. My priority is to capture knowledge of people of color and support it and highlight it. And a lot of people want that.

Anon: I think people are looking for that, Cyndi—and the more you do that, the more voice you give to these communities. You know, the reason why we created the climate network was because all these climate change and environmental conferences that were taking place in Puerto Rico were taking place within four walls, where the folks that were being invited were groups of scientists or professors or foundations—but communities weren’t being involved. And they’d invite the executive director of an organization to come in, collect that knowledge, and bring it to the community. But the more access you give of that information to the community directly, instead of going through an organization, the more people understand why they’re being asked to do things like reduce, like recycle and reuse, to conserve the environment—the more they can tie one thing to another. And in many cases, I heard over and over again scientists say in conferences, “And we’ve learned from the community that they already knew this stuff” and “We figured out that it was important to start working with the community.” Well, see, you should have known from the start that it was important to be working with the community. We should have known that the community has a whole lot of this knowledge already. Let’s connect it, you know? Let’s really bring it together. And sometimes, you see that the community is afraid of scientists, because they say, “Well, they’re going to spend a lot of money on analysis, and we’re never going to get anything done.” And you’ll hear scientists say about the community, “Well, you know, they’re gonna say they know stuff, but they don’t.”

And this is where empathy, understanding, and communication need to come into play. These are things we may think are so obvious, or we may think are so simple that it’s a given that people understand. But it’s those things that are going to enable these conversations to take place in an effective manner. You know, if scientists take half the empathy and understanding and wanting to hear and learn that I use when I talk to communities— man, we bridge the gap! And if communities do the same thing, vice versa, vis-à-vis scientists, and say, “Let me just listen to them—let me try and figure out what it is exactly that they’re trying to communicate to me. And if they can’t communicate it in a way that’s effective, let me ask the questions to make sure that they communicate it in a way that I can understand.” Boom! We have a connection. And I think that those gaps are important to fill.

CS: Yes. So, what’s your old organization doing now? Last time I was there, it was work around Hurricane Maria.

Anon: Yes. They were doing work around energy. Giving out solar lanterns. We ended up giving out thousands of solar lanterns door to door.

CS: I still have people thanking me for the lamps and telling me how much it meant to them. They still have the lamps.

Anon: They clean them up and they shine them and they put them away. It’s the funniest thing, you know? They give them the Puerto Rican love. Many said that the solar lanterns are an example of what the whole island can do by going 100 percent solar. I’ve gone back to houses where people still have the lanterns and still use them when the lights go out. I have seen on Facebook where people who were given lanterns post a picture of the lantern when the lights go out, and they write, “Thank God for giving me this gift that I can continue to use on days like this”— because the lights still go out. I mean, I know in my case, my lights go out twice a week for hours at a time.

CS: When I was there last year for my dad’s funeral, it was during the earthquakes. The day before I was leaving, the whole island shut down. I was so freaked out, because everything closed—the hotel, the supermarkets—and everybody was so casual about it. Everybody just brought out their generators.

They were like, “It’s just gonna be like this for a few days, so get some water.” I was freaking out! Everybody was so matter of fact about it. It was like a party. Like it was normal. And it was so hot. It was just so hot. And I realized, “Oh, wow, this is normal.”

Anon: So there are two things to that, right? One is—and I think about this every single time I get off an airplane and come to Puerto Rico—that we’ve become so complacent with having the minimal. Having the minimal services—having poor public education, having minimal electricity service, having roads that are destroyed, driving under poles that could literally fall on us.

CS: I mean, they could kill you, right?

Anon: They could kill you. And then, we have really bad legislators, and we continue to reelect them. We’ve become so normalized about that, that we don’t have higher expectations.

CS: When did that happen? It wasn’t always like that. I remember I would go there and everything was so crisp, and everybody voted.

Anon: Yeah.

CS: It seems like so long ago.

Anon: Well, the voting still happens. But they are settling, and they know they’re settling. And I don’t even want to get into the whole issue of statehood versus independence versus, you know, commonwealth. Because I think that we’re at a point where we’re just okay with living the way we’re living, you know? But on the flip side of that, because the electricity has gone out so much, because we are living so fragilely, because the economy is a mess, because we have really bad legislators, because of Hurricane Maria, we are better prepared for crises now.

CS: Say that again.

Anon: We’re better prepared for a crisis.

CS: Because of what? Because of everything that’s happened?

Anon: Because of Hurricane Maria, because of everything that’s happened.

CS: So people just know how to deal with crisis.

Anon: So, when a crisis comes, people are relaxed and know what to do.

CS: Wow.

Anon: “I have this, this and this, and this in the house. All I have to do is do this, this, and this.” So there’s a flip side to it—there’s a negative, which is we become complacent with, you know, everything. And then, on the other hand, we’ve become better prepared for crisis, which is: “A crisis comes, I’m gonna take it easy. I know what I have to do, and I’m going to do it.” So, you have those two sides. But, you know, last time we left and returned, my wife said, “Oh, my God!”

CS: What is it like? Because of COVID? Is there lockdown in Puerto Rico?

Anon: It’s been on and off lockdown. It’s not a heavy lockdown right now. It’s pretty open now.

CS: So, people aren’t vaccinating?

Anon: People are vaccinated. I think 60 percent of the people are vaccinated.

CS: Oh! That’s good!

Anon: Yeah, it’s really good. What my wife was referring to was that the minute you get back, you see the holes in the street, you see the infrastructure is a mess, you see all the buildings are a mess. You see the light poles hanging by a thread. And you just still see the results of Hurricane Maria, and you say to yourself, “My God.” And it’s funny, because it hit my wife—it didn’t hit me. But it didn’t hit me because I knew that we have become accustomed to complacency. I knew that we have become accustomed to living in the situation that we are living in. So, the minute we got on the highway, she started looking around, and she saw the highway, she saw the buildings, and she said, “Oh, my God! It’s really hitting me right now what we’re living in.” And I can’t even walk on a decent sidewalk. You know what I mean?

CS: Yeah, I feel it when I go there. I feel it. And then I remember what it was like when I was a kid. And it almost feels like la-la land.

Anon: What happened, right?

CS: Yeah, it’s very different. If you’re not used to Puerto Rico, when you go there, living in a state of a crisis—you can’t fully recover from it, it does something to your psyche. I was there for maybe five days, and it was very hard for me. And the earthquakes when I was there were very strong. I felt very unsafe. I felt like I was going to get swallowed up by the ocean. I was like, “How do people live here? This is so stressful.” The lights went out. It was so hot. The fumes from the generators. Everybody was used to it. I had a headache from the fumes.

My brother lives in a gated community. And as we were leaving, as we were driving out, I noticed that the guy at the gate had a big automatic weapon. And I looked at my brother, who didn’t flinch, and I said, “Why does the security guy have an automatic weapon?” Like, he’s not in a war. And he said, “Oh, that guy, that’s his own weapon. He’s crazy. He just likes to bring his weapon to work.” And I said, “And nobody does anything?” And he said, “Who’s gonna do anything? There’s no police, really. This is not what people are paying attention to.” That was my vision on my way to the airport. It was almost like something out of a movie. It was pitch black, because there was no electricity. And I was just trying to get out. I felt like I was in a movie trying to catch the plane before everything collapses. And then you get to the airport, and everything is closed. There is just one place that opens at a certain time, and everybody stands outside to wait for that place to open to get food. It’s like nothing works.

Anon: Right. You’re 100 percent right.

CS: It’s very emotional for me when I go there. I don’t like to go there, actually. My son wants to go, and I feel bad taking him, because this is the first time he’s going to see it. But I feel like I missed those chances for him to see it. And this is what it is now. And he really wants to go. And my daughter, she had been wanting to move back to Puerto Rico. She really loved it there. She wanted to do creative work there.

So, we were there for that, and we were walking in San Juan, where we were staying, on the main street there with all the restaurants, Calle Loíza—and the street was broken up. And I remember I asked someone, “Why is this stuff in the street?” They said, “Oh, people cover the holes themselves, they just mix cement and cover the holes themselves.”

Anon: And that’s the complacency I’m talking about.

CS: But the amazingness of the people, though! People were creating all these microbusinesses, and there was all this healthy food that was delicious. And I think that’s what struck her—the people. She would say, “The people here are just so unbelievable. Look at how it is, and look at how nice people are.” Over here, you have a little thing in the street, and someone’s ready to kill you. Over there, people are living this crazy existence, and they’re sweet. You know, everyone’s like, “How you doing?” People sit down at the table next to you and start talking to you. They recommend dishes. She had never experienced that, you know?

Anon: Right. And those are the things that keep people in Puerto Rico, right?

CS: I can imagine.

Anon: Those are the things that, when we leave Puerto Rico, we miss. I have this sort of inside joke that I do when I’m in the U.S. Basically, I get into an elevator, and other people are there, and I’ll just randomly say, “Good morning.” Or I’ll say, “Good afternoon.” Or I’ll say, “Good evening.” Because I know, most of the time, people will not say it back. But if I do it in Puerto Rico, they will always 100 percent say good morning back, or good afternoon, or good evening. You know? And those are the things that remind me that the beauty of Puerto Rico is not only the nature, right? The environment of the island, the beaches, all of that. It’s our people. So regardless of all the madness that we see, the people keep you there. And I think that’s a powerful thing. It’s a powerful statement. And I think that in times like these you need something that says to you that there is hope. And it’s those reactions that you’re getting from folks that let you know that, regardless of our current crisis, there’s still hope. Because that love is being extended from one person to another on the island, no matter where you’re from or who you are.

CS: Is that part of the culture?

Anon: Yeah.

CS: I wonder what part of the culture contributes to that? That hope. . . .

Anon: I think a large part of the culture contributes to that. It’s island-wide. You could find that just as much in San Juan as you could find it in Cabo Rojo, or Humacao, or Loíza, or Ponce. I’ve seen it everywhere. I saw it equally in Vieques. And so this constant love that we get from one another allows us to really be able to feel that hope, regardless of the situation. Feel that you’re in a circle: that regardless of whether or not there are times when maybe the situation could make someone else feel alone, you don’t, because you feel part of a community.

CS: People take care of each other.

Anon: People take care of each other. And it’s funny, because I have a friend who, when one of my staff, male, opened the door for her, said, “You guys don’t need to open the door for me.” Coming from her, it didn’t surprise me, because that’s something that’s very American—you know, to show our ability to be independent and that we can do it ourselves. And I said, “I’m sorry that he did that. But this is what we do in Puerto Rico. We open the door for each other.” I said, “I could tell you of countless times that I’ll open the door for him, and I’ll say ‘after you’ and he’ll say ‘no, no, after you,’ and we get caught up in that whole ‘after you’ thing. But that’s how Puerto Rico is in general.”

I can give you a number of examples. Just yesterday alone—my family went to take my mother to dinner, and I remembered it because, as I opened the door for another family to come through, my family moved to the side, automatically. I didn’t have to tell my family to move to the side—they moved to the side on their own. The other family came through, and then I was going to hold the door for the husband to come through. He says, “No, it’s my turn.” And then we all went through. And then he left. We still live in that sort of world that existed in the U.S. in the forties and fifties, where there were gentlemen and there were ladies, and chivalry was a good thing. All of that still exists here in Puerto Rico.

CS: I think there’s a name for that. Welcome culture? My ex-husband is from Sudan, and in Sudan it’s the same thing. When we used to go visit Sudanese people when we lived in California, whenever you went to a Sudanese person’s house there were sweets and the best food. Everything that was the best was saved. And you could only eat it when guests were there. So the kids would get all happy when there were guests. I’ve been to Sudanese people’s homes where they insist that we sleep in the master bedroom, because it’s the nicest bedroom. And I’m like, “I can sleep in another room, the kid’s room.” And it’s this thing—they always say you give the best to the guests. I remember when I saw that I thought, “Oh, that’s how Puerto Ricans are.”

When I lived with my mom, people would just show up. A whole bunch of people would just show up on Saturday, and the whole day would be changed. Whatever we were doing, now we’d just be entertaining this family all day. And we would be doing it happily. And I remember when I lived in California, one time I stopped by a friend of mine who lived on the same block, and just knocked to see if she was there, because she had a kid that was friends with mine. And she was upset that I didn’t call first. And I thought, “Oh, so I have to always remember that there are these different cultures.” So, there’s a name for it. It’s not “welcome culture.” But you give the best to the guests. Or to other people, you know? There isn’t a thing about, you know, hiding things when the guests come, you know what I mean? I’ve seen people that do that. And it’s just like, what?

Anon: What is that? We put out the best glasses when the guests come, you know? Once when we had guests, I accidentally grabbed these metal cups that I get a kick out of drinking from, because they stay cool. And my wife goes, “No, what are you doing? Put out the best glasses.”

CS: You’re like, “These are the best!”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Anon: Yeah, I’m thinking in my mind, “These are the best.”

CS: So what are you doing now? When did you leave your previous job?

Anon: I left some time ago. It was one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever had to make. Currently, I’m working with a foundation and continuing my work.

CS: There are so many different people that I’ve talked to about this, but you have such a different take, because you’re in the middle of all these different systems: the community. . . and you get this nonprofit sector, the people, the funders.

Anon: I think it’s really good work, the work I’m doing now. And it’s given me a lot of peace in terms of economically stabilizing my family. I gave 120 percent of me, you know?

CS: That’s all? I think you gave more than that. At least 150.

Anon: Yeah. And that means I put my family in a certain difficult place economically. But I believed, and still do, in everything we were doing—with a passion that I still feel today.

CS: You miss it?

Anon: I miss it hard.

CS: What do you miss about it?

Anon: I miss being with all the members in the community. I miss having them telling me what to do all the time. I enjoyed that. You know, leaders don’t generally want people telling them what to do. I wanted it. I welcomed it. I’m glad you got to see it.

CS: I’m glad I got to see it, too! I want my son to experience Puerto Rico. He’s never been there. I have this thing about the different parts of Puerto Rico, you know, the different towns, and how they’re all like their own world. I never do itineraries, but I kind of want to now, because I want to make sure that I do things that really show him Puerto Rico. So, I don’t know, how do you cover Puerto Rico? You kind of can’t, right? You have to like, pick a few places.

Anon: Yeah, you can pick a few that will give him a good cultural perspective, where he can feel like he has connected.

CS: Do you know what those would be?

Anon: Yeah, for example, I would definitely take him to Isla Verde and see the beaches there, and maybe make some stops to see some of the environmental groups that are out there, and watch what they’re doing. There are environmental groups on Isla Verde and in Santurce that are doing really great work reestablishing dunes in the area, which is so important because of climate change. So, they plant vegetation in the area.

There are groups that take care of the leatherback turtle. And when the leatherback turtle comes in and nests, they take care of the eggs, and then form this pathway for the hatchlings to come out into the ocean. And then that becomes this whole spiritual moment with the community. In some cases, they’re just quiet, and just sharing energy with the hatchlings as they catch the waves. It’s the coolest thing. I remember I took my daughter to one. She would scream every time a turtle hit a wave. She’s like, “Aah!” And I remember the folks there started saying, “Shhh.” It’s very spiritual, very awesome. And I think you and he would love that. It’s a very powerful spiritual moment, seeing these hatchlings going out and experiencing life for the first time. And slowly trying to get to the ocean to start living its life. It’s amazing.

Another awesome place—it is a heck of a drive, though—is Casa Pueblo, a nonprofit community group in Adjuntas. Along with the social justice work they do there, they also have all sorts of gardens, a butterfly habitat where they raise monarchs and grow their own coffee. You can buy a packet of coffee there, which is great.

I would take him to Loíza, and if there’s a bomba group playing out there that night, I would take him there, and tell him the story of how Loíza was created, and how the people live. I would take him to Old San Juan, definitely. And take him to El Morro and tell him the story of El Morro and the story of Old San Juan.

What else? I would even take him—and this sounds lousy, but there’s a reason for this—I would take him to the malls. Because I think sometimes people think that Puerto Rico is this “third world” country where we’re still wearing, you know, leaves for pants and stuff. We also need to put things into perspective—you know, it’s still just as fashionable as the U.S., and still just as “in” as the U.S. There are just things that are different about Puerto Rico, that’s all. Culturally different?

And I would take him to Piñones—hardcore. Piñones is a must-stop.

CS: Why?

Anon: Because there’s a culture there…it’s part Puerto Rican, part Dominican. They make frituras……. When

folks in the U.S. picture a restaurant that they want to go to on an island, it’s something like Piñones.

CS: When I was there one time I went through the mountains on the pig mile. And even though I’m a vegetarian, it was so beautiful up there! And there were all the places to eat and dance. It was just so beautiful. I love the mountains.

Anon: There are two more places that I would suggest happily. One would be El Yunque.

CS: Is it open all the way now? I went there back in—oh my God, it was so beautiful.

Anon: It’s not completely open. If you go, you can call ahead of time and make reservations and buy your tickets.

CS: What about Camuy?

Anon: Cavernas de Camuy are really amazing. I would definitely put that up there. It’s an awesome experience. It’s him in the environment and really appreciating nature. I think that’s a beautiful place to take him.

And if there’s another place that I would definitely say to go to it’s Cabo Rojo. The salt flats of Cabo Rojo. And the beach is called Playa Sucia. This is going back as far as the Tainos, who were the first to access salt from the salt flats in Cabo Rojo. And since then, that was an industry that we had. Currently, there is no industry there in the salt flats—now it’s a reserve. But it’s dealing with some challenges due to climate change, and it’d be great if you could see that before it starts to disappear. And the spot that I would suggest is Playa Sucia, where the salt flats are, because it’s an enclosed beach. It’s the saltiest salt water you’re ever going to swim in, but it’s clean and clear. And then at the very top on the right-hand side, there’s a reef with a cliff, but with a lighthouse on it that’s closed. It’s now owned by the municipality. And you can take pictures in front of the lighthouse, and then on the other side is just a cliff. And you can sit there, and you feel like you see the world, you know, and it’s just ocean, all ocean. It’s amazing. It’s a place where you feel serenity, you feel peace. You feel connection with the environment that to some extent you feel with the beaches out here, but you really feel it there. It’s my favorite place to go. So when my wife says, “Hey, what do you think if we go to Cabo Rojo?” I’m packing already, you know what I mean?

CS: That’s so cool. I think if I was in Puerto Rico, I would want to go to all the towns. I just find the whole thing so fascinating, that there are so many towns that have their own character and festivals. Thank you so much. This is great.

Anon: You’re welcome.

CS: It’s so great to hear that you’re doing well and that your family’s doing well. I’m just really happy for you guys.

Anon: Thank you. And Cyndi, you know, there’s only one ask I will ever, ever, ever, in my lifetime, have of you. And that’s that, whatever you do, keep blasting Puerto Rico.

CS: I try, you know? My work has grown so much, and I feel like I’ve been trying to figure out how to do that. When I first started covering it, people were like, “What? Why is this [being covered] here?” And I would say, “Okay, first of all, not only is it part of the U.S., but it is at the forefront of almost every issue that we’re dealing with.”

Anon: Right.

CS: And so people got really interested in it. And then other work happened. So, I’m thinking, okay, how do I stay in touch with what’s happening in Puerto Rico? I know people in different institutes and stuff, but that’s not always the voice that I want. I need one or two people to cover what’s going on, because so many things have happened and I can’t track it all. After Maria, there were so many things happening democratically, so many movements that I wanted to cover. But I would have had to focus just on it. So much was going on. And I wasn’t there. So it became hard.

Anon: I can also share news I come across with you. If I could be a help that way, a resource . . . because the power that you have to highlight what’s going on here is amazing.

CS: I want it. And people want to hear that.

Anon: Definitely.

CS: I wonder what’s going to happen, and what’s the future of Puerto Rico. I mean, I hope it’s good. I hope that there’s good stuff in place. And that there’s some kind of normality, whatever it becomes.

Anon: It feels like it’s maybe still a decade away.

CS: What do you think has to happen? Is it about the politicians?

Anon: Part of it is the politicians. I think we need to continue to build strong movement. But I also think that the foundations here need to start thinking differently about the types of programs that they fund.

CS: How do you think they should be funding?

Anon: I think sometimes they play it too safe and don’t fund work that is movement based. They fund after- school programs, which are important. They’ll fund other programs that are equally important, but when it comes to movements, organizing, and that sort of stuff. . . .

CS: No one’s funding that?

Anon: It’s rare to see foundations funding it out here. There are very few that fund it, and there are very few dollars for it. And that’s why when you get opportunities from foundations in the U.S., that can find a way to have the structure to be able to support a program in Puerto Rico, you love it, because they’re not going be shy about funding movements.

CS: So, U.S. foundations will fund movement.

Anon: U.S. foundations will fund movement.

CS: But not the Puerto Rico ones.

Anon: It’s not always the case in Puerto Rico.

CS: Interesting.

Anon: And the dollars are a lot less here.

CS: Do you know any funders in Puerto Rico that are funding movement?

Anon: The Puerto Rico Community Foundation. They’re one that will fund this kind of work. But other foundations just straight up won’t.

CS: And in U.S.?

Anon: There are many that do. They’re really good for that. So, thank God for foundations like those that are willing to fund programs like that. That’s what they want. That’s what they’re looking for.

CS: If you had that money, what would you create?

Anon: I would create a social justice organization that’s able to do several things. It would have to do some work on electoral reform. It would do some sort of work around public education, the quality of public education. It would do something around climate change and the environment. And I know, these are some key topics that I’m mentioning, but I think that there are topics that we don’t have enough people working on in the ways that they need to.

CS: How much money would you need to do that?

Anon: I think something like that can be done in Puerto Rico with five to six hundred thousand dollars a year, easily. Whereas in the U.S., that would be in the millions, probably.

CS: I would love to see this. You are so awesome. I appreciate you so much. Thank you so much. Anon: Thank you, Cyndi.

Notes

- Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], August 2021), www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/.