“The tyranny of success often can’t be bothered with complexity.”

—Father Gregory Boyle, founder of Homeboy Industries, Los Angeles

Over the past year or so, the Nonprofit Quarterly has hosted a lively conversation about the merits of metrics, strategic philanthropy, and other cutting-edge practices associated with sophisticated contemporary grantmaking. (It is worth noting that NPQ is almost the sole venue for this sort of spirited, balanced back-and-forth about issues that are too seldom discussed in the nonprofit world.)

As useful as the discussion so far has been, we’ve only begun to deal with the larger problem beneath questions of method and technique. That problem is—as Jesuit priest and founder of Homeboy Industries, Father Gregory Boyle, puts it—the “tyranny of success.”

Modern philanthropy famously demands success in the form of tangible, objective, measurably positive outcomes. Each new generation of grantmakers comes onto the scene and utters this sentiment as if it had never occurred to anyone before. But, of course, it’s been at the heart of philanthropy since John D. Rockefeller enunciated it one hundred years ago.

This demand, in turn, requires nonprofits or those who audit or evaluate them to make sharp distinctions of their work into success and failure. And yet, especially among hard-pressed populations that have always been the peculiar charge of the nonprofit sector, that distinction often is not so clear. What today looks like a success in a few months may turn into a failure, and what today looks like a failure becomes a success. More important, failure and the way it’s accommodated contribute decisively to success. But the measurers have no way to countenance such complexity.

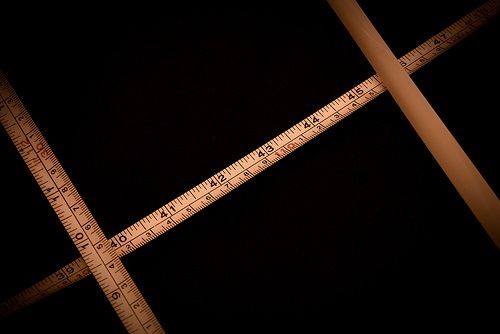

In order to construct the elaborate edifice of Big Data, there simply must be, deep down at its very foundation, a clear, distinct separation of the sheep from the goats, an assignment of “1” (success) or “0” (failure). Just as the vast digital world is built on “0s” and “1s,” so is the empire of metrics. The most remote and abstract regression analysis depends on that initial, radical division—no hedging, no hemming or hawing, just putting it down on the scoring sheet as a “1” or a “0,” leaving the rest to the evaluators at foundation headquarters or at the university.

But this grand divide isn’t as simple as it seems. Alicia Manning, program officer with the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation in Milwaukee—where I once worked—recently took me to meet George Bogdanovich, cofounder of that city’s Community Warehouse. Among many other things, the warehouse accepts donated surplus construction material, appliances, plumbing fixtures, and so forth, and sells them at reasonable prices to those who are rehabilitating houses and stores in the inner city. They’ve now begun using some of the materials to prefabricate doorframes and sink cabinets, which provides jobs while teaching entry-level carpentry skills. All Warehouse employees have come out of prison or off the streets.

As happens so often when I visit frontline nonprofits—okay, sometimes it happens because I raise the question—we started discussing the problem of measurement: the demand that nonprofits classify their efforts into either success or failure. This clearly is a problem that George wrestles with regularly and without any prompting from impatient funders..

He brought up the example of Joe, a pimp and drug dealer who had been one of his first employees. Things had gone well for a while, but then there had been a couple of thefts. George chose to follow the advice dispensed by the director of the recovery community where Joe lived: “Fire his ass.” Even as we stood in the drafty warehouse talking the question over, though, George was awaiting the call he gets from Joe every year around Christmas. He always checks in, telling George how things are going, and thanking him once again for giving him the opportunity for his first job out of prison—even though George had, indeed, fired his ass.

“So,” George asked—probably more of himself than of us—“was my experience with Joe just a failure?”

“No way you don’t count that a success,” Alicia immediately insisted.

In moments of pridefulness, I refer to Alicia as my student, since twenty years ago I took her around on her first site visits among Milwaukee’s grassroots leaders. But the fact is, she has far surpassed whatever I had to offer her and now navigates with ease among the Bradley Foundation’s smallest inner-city grantees. Her grant recommendations are based less on numbers than on the “local wisdom” that she gathers with her own eyes and ears and finely tuned BS-detector. She has no problem dealing with the inadequacy of “1s” and “0s” and the ambiguity that Joe poses to classification. But how many other foundation program officers, academics, or evaluators can claim that hard-won skill?

I first struggled with this problem in the 1990s as Alicia’s predecessor at the Bradley Foundation, helping to support the National Commission on Philanthropy and Civic Renewal, which became the namesake for my present center at the Hudson Institute. Chaired by now-Senator Lamar Alexander, half of the commission’s membership had been drawn from grassroots leaders whom Alexander had met on his travels or whom Bradley had come to support in its efforts to stimulate interest in faith-based civic institutions. The commission visited each of the grassroots members’ projects in turn.

Commission member and Episcopal priest Father Jerry Hill, for instance, had initiated a program in Dallas, the Austin Street Shelter, which ministered to a very marginal group: the vulnerable, mentally ill homeless (that is, homeless individuals who were all too likely to be victimized in the mainstream shelters) in that tough part of town. It was nothing at all fancy—a warehouse-like structure where the homeless would come each evening to pick up a pallet and sleep on the floor. Sponges and a bucket of bleach water stood beside the stack of already clean pallets, for those who wanted to wipe them down again. But around the periphery of the main room were smaller, semiprivate sleeping quarters for those who wished to begin their journeys off the streets..

Father Hill introduced us to one such journeyer. She had been a Braniff stewardess until the airline went belly-up, leaving her jobless in a bad economy. That began a downward spiral to the streets. There she became known as the “Bug Lady,” because of the vermin in her hair. By the time she reached the shelter she had become so unstable that female staff had to help her shower. But now she was on her way back up, with her own bed in a semiprivate room, and a job—saving up so she could move to her own apartment.

The whole process—the climb from the streets to the semiprivate room and now possibly onward to full independence (a climb by no means yet complete, and by no means guaranteed to have a happy ending)—had already taken over a year and countless hours of intensive staff attention, racking up who knows how much per capita cost.

The commission’s final report concluded that we need to be more generous toward the work of smaller, often faith-based groups like the Austin Street Shelter that do so much of the unheralded heavy lifting among America’s most vulnerable and marginalized. Still, its number one recommendation for philanthropy (John D. Rockefeller, yet again) was to focus on overcoming the gap between American generosity and the “actual impact of giving on those in need,” a gap that “must be closed by reorienting our giving toward organizations that get, and can demonstrate, real results.”

But how, I wondered, did the commission’s own example of the Austin Street Shelter fit into its demand for “real results”—for success? After months upon months of concentrated, intensive staff time and effort with the Bug Lady, do we finally just tally her up as a “1”? Is that even remotely like the “1” also used to depict, say, the depressed college dropout who quickly recovers from his fling with drugs and gets back on his feet with minimal help from the staff?

And if, in spite of monumental efforts, the still-fragile Bug Lady slips back onto the streets, do we now count her as a failure? Do we erase the “1” and replace it with a “0,” discounting entirely the shelter’s time, investment, and promising initial progress that might bear fruit later on?

Our assignment of “1” to the Bug Lady is at once far too inadequate a way to describe the shelter’s work and yet far too firm and final, given the realistic prospects for someone in her situation. But the shelter’s outcomes-oriented funders would insist nevertheless that it make these sorts of stark and sterile judgments, even among those least susceptible to being sorted so conclusively into successes or failures.

Another example of the insufficiency of “0s” and “1s”: This past fall, I attended a memorial service in Denver for the late Bob Coté, founder of Step 13, a program aimed at bringing alcoholics and addicts off the streets. Coté could be cranky, outspoken, and cantankerous—utterly defiant of the pieties and orthodoxies of the large social service establishment. He broke onto the national scene briefly in the 1990s, testifying before Congress against the federal practice of mailing SSI checks to local bars, where they would become, in essence, running tabs for alcoholic recipients. The Social Security Administration was subsidizing “suicide on the installment plan,” he vociferously charged.

I had always wondered where he had acquired this burning animus against SSI, and in the testimonials to Bob I heard the reason: he had himself come off the streets in the 1980s, and brought a dozen other guys with him into sobriety. One of them was Billy, his proudest success, an old drinking pal who was the “smartest guy he had ever met”—able to spout pages of Shakespeare from memory. But once sober, Billy had signed up for SSI. And, for the first time, he could afford the “good stuff”—Crown Royal—if he so chose. He did. He was dead within months of leaving Step 13.

A success become a failure, a “1” replaced with a “0.” And yet, far from discouraging Coté it gave him the fire to testify before Congress and, more importantly, the determination to redouble his efforts to bring more of his old acquaintances off the streets. To the end of his days, Bob talked wistfully about losing Billy; a small plaque devoted to Billy’s memory hangs on the wall of Step 13’s main meeting room. Without that “failure” and the resolve it enkindled, how many successes would never have happened?

Failures that we should count as successes, toehold successes that tremble perpetually on the edge of failure, and failures that stoke the energy to keep striving for success. These nuances and complexities leave nonprofit leaders troubled and uneasy about the demand to freeze-frame their work into “1s” and “0s.” Everything about their daily experience tells them that success and failure are far more complicated and nuanced than that.

No one captures this problem more directly or bluntly than Father Boyle. Homeboy Industries’ work focuses on young Hispanic people caught up in L.A.’s powerful gang scene. It offers a dizzying array of social services and enterprises, including a day-care center, graffiti removal, silk-screening, a farmers’ market, catering, a bakery and café, a grocery, and tattoo removal.

Like all the groups we’ve been discussing, Fr. Boyle has any number of “success stories” to tell, many of them recounted in his recent Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion. When readers arrive at chapter 8, promisingly titled “Success,” we of course expect a final crescendo of successes, especially after the teaser opening lines: “People want me to tell them success stories. I understand this. They are the stories you want to tell, after all.”

Then he does tell us stories, six of them, about Scrappy, Raul, Shady, Manny, Ronnie, and Angel—all young people whom Homeboy Industries had been easing out of the gang scene. Each of the stories begins with hope and expectation, as Fr. Boyle and his staff take heart from promising first steps toward more productive lives. Each looks to be a “win” for Homeboy—a “1.” By the time chapter 8 concludes, however, each of their lives has been snuffed out by gunfire. “Success” doesn’t give us a single happy ending.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Fr. Boyle isn’t being morbid. He’s challenging at its root what he calls the “tyranny of success”—our unforgiving system of “1s” and “0s.” He draws some comfort, he maintains, from Mother Teresa’s famous reminder that “we are called upon not to be successful, but to be faithful.” He adds, “This distinction is helpful for me as I barricade myself against the daily bread of setback[. . . .] For once you choose to hang out with folks who carry more burden than they can bear, all bets seem to be off. Salivating for success keeps you from being faithful, keeps you from truly seeing whoever’s sitting in front of you.”

Scrappy’s gangland-style execution while working on a Homeboy graffiti crew, for instance, prompts these ruminations from Fr. Boyle: “Was he a success story? Does he now appear in some column of failure as we tally up outcomes? The tyranny of success often can’t be bothered with complexity. The tote board matters little when held up alongside Scrappy’s intricate, tragic struggle to figure out who he was in the world.”

Fr. Boyle’s faith tradition directs him toward the biblical figure of Jesus, of course, who challenged the world’s framework of success and failure. Jesus snubbed the rich and powerful, seeking out instead the company of prostitutes, publicans, the blind, halt, and lame, and other marginalized individuals of his time. As Jesus stood with them, Fr. Boyle insists, so we are called to stand with the unemployed, the adjudicated, gang members, and other marginalized figures of our time.

Yes, of course, we work for success in bringing about healthy changes, he maintains. But we cannot come to regard those changes as the sole purpose of the work. “You stand with the least likely to succeed,” he continues, “until success is succeeded by something more valuable: kinship.”

I discussed these matters recently with my mentor, Bob Woodson, founder of the Center for Neighborhood Enterprise (CNE), which works to strengthen grassroots groups around the country. As a strong believer in measurable outcomes, he comes at this from a slightly different angle. He makes the case that this isn’t an “either/or” question, and that faithfulness and success are, in fact, intertwined.

I was in his office several months ago when he had to take a call—“had to,” because it was from a prison pay phone. Sammy had once been part of a major success story for CNE—a neighborhood truce it had negotiated that quelled gang violence in one of Anacostia’s toughest neighborhoods. But unlike so many others from that truce who had gone on to productive lives, Sammy had lost his way and was now finishing up a ten-year stint in prison. Bob had to work hard to overcome his initial hurt and disappointment, but finally he had and now talked to him regularly. As I listened, he offered to put some money into Sammy’s commissary account and to fix him up with some suits when he was released.

I pointed out later to Bob that, even after hearing him speak for thirty years, I had nonetheless never heard about this aspect of his life and work. I knew he would do anything to pull young men and women out of gang life, and I had often heard him celebrate their successes as he carried their hopeful stories to audiences across the nation. But until the coincidence of a call he had to take with my presence in his office on other business, I had never appreciated his willingness to stand as well with those who hadn’t made it—his unheralded determination to be faithful to them until they were ready to try again.

But as he explained, were he just to stand with the successful, there would be far fewer of them. Those who “carry more burden than they can bear” don’t yield their fates readily to outsiders—those whom society trains and pays to “fix” others through programmatic interventions. They might, however, share their burdens with those for whom they’ve come to feel kinship—those who were once on the same destructive paths but left them and are now ready to stand faithfully and unflinchingly beside others who are ready to leave, through all their advances and setbacks, their small wins and occasional substantial losses.

This doesn’t mean the sort of tolerance for any and all infractions that verges on enabling. But it does mean knowing when to make stern demands for more responsible behavior and when to display mercy, to give second chances. Even Fr. Boyle, who confesses that he is a softie, must nonetheless occasionally “fire [someone’s] ass.” But this is how he approaches it. “I call the person in and say, ‘The day won’t ever come when I will withdraw love and support from you. I am simply in your corner till the wheels fall off. Oh, by the way, I have to let you go.’ They always agree with me. Nearly always.”

The tension between faithfulness and success, however, can never be entirely resolved. As Fr. Boyle notes, “I’m not opposed to success; I just think we should accept it only if it is a by-product of our fidelity. If our primary concern is results, we will choose to work only with those who give us good ones.” Groups like the Austin Street Shelter, which set out initially to minister to the hardest of hard cases among the homeless, might be tempted to mix in more of those who are only momentarily down on their luck—who require far less effort and attention than the Bug Lady and who show results far more readily—in order to boost the “1s” that can be reported to funders in thrall to the tyranny of success.

But the temptation to “cream” isn’t the worst aspect of the tyranny of success. The much larger burden it imposes on those who work at the outermost margins of society, I think, is that it taps directly into and aggravates an inner turmoil experienced by the most effective grassroots leaders. As suggested by our examples, they already torment themselves every day—and, more than likely, deep into the night—with the question of success and failure. “Was I too tough today? Too soft? Did I ask too much? Too little? What could I have done differently?”

These questions don’t disturb their rest because funders have raised them; they are questions that, as faithful servants, they already incessantly put to themselves, and probably more sharply than any funder ever could. The suggestion that it takes the imposition of an external metrics framework to awaken their yearning to be effective is at best a well-intentioned misunderstanding and at worst a gross insult.

When faithful nonprofits lose someone—to drugs, homelessness, gang violence—they’re upset not because it messes with their tally of “1s” and “0s”; they’re disappointed, perhaps even heartbroken, because they were hoping, betting, counting on that person to make it this time, perhaps against a long history of failure, relapse, and disappearance. In turn, that degree of faithfulness and trust by the nonprofit staff and other program participants may well be, in the darkest moments for the person on the edge, the sole factor that keeps one foot stepping in front of the other in the long, seemingly impossible climb back to a healthy life.

Ironically, one way the tyranny of success does not manifest itself is in the ruthless defunding of “losers” in the name of supporting only “winners” among grantees. For all the tough talk from foundations and evaluators about paying only for outcomes rather than efforts, the fact is that this resolve seldom gets beyond verbal swagger, as surveys for the Center for Effective Philanthropy have repeatedly found. Indeed, one of the reasons frequently offered by foundations for not releasing publicly the results of their evaluations is that it might embarrass poorly performing grantees.

If the day ever comes when metrics bluster at last acquires some teeth—a day fervently wished for by so many philanthropy leaders—we may well begin to cull out the smallest, least “efficient” nonprofits working with the most vulnerable. Then the tyranny of success will have at last consolidated its domain.

Meanwhile, success’s tyranny manifests itself more subtly, I think, in the remorseless demand for good news from the front line, the insatiable appetite for stories about winners rather than losers. Program officers—and here I report from personal experience—make site visits and listen with smug self-satisfaction to stories about the wonderful changes that have been wrought with the foundation’s help. Photographers and public relations specialists come down and capture in word and picture heartwarming scenes for the annual report. The measurers render those stories into “0s” and 1s” and ship them off to the foundation or university for further processing.

But once the program officers, report writers, photographers, and evaluators have left the site loaded down with success stories—probably without touching the plastic platters of food and drink that were purchased at some sacrifice for the occasion—the nonprofit’s staff is left to deal alone with the daily diet of bad news. They must bear by themselves the quiet awareness of the kinfolk they’ve lost or are losing, the “failure stories” no one wants to hear, the setbacks for which a “0” is hardly adequate to describe the hurt and disappointment they cause.

Not only that, we even tend to dismiss as “unprofessional” the inner turmoil that failure may induce in frontline leaders. They shouldn’t get so involved, we advise from afar; they shouldn’t take failure so personally. It’s the peculiar luxury of program officers, evaluators, and writers to retire quickly to their downtown suites bearing neat packages of good-news numbers without ever becoming intellectually or emotionally involved in the complex and ambiguous process that produced them in the first place. After all, they can say to themselves, they’re simply being rigorous, objective, neutral, and detached—all of which are prerequisites of professionalism.

But, as Lisbeth Schorr pointed out years ago in Within Our Reach: Breaking the Cycle of Disadvantage, the most successful social service workers are precisely those willing to step outside self-imposed professional limitations and bureaucratic boundaries in order to form immediate, personal bonds with clients—bonds that are essential to but by no means contingent upon “good outcomes.” As she put it, “these professionals have found a way to escape the constraints of a professional value system that confers highest status on those who deal with issues from which all human complexity has been removed [. . . .] This suggests a fundamental contradiction between the needs of vulnerable children and families and the traditional requirements of professionalism and bureaucracy.”1

As a nation, we’ve learned to compensate for the constraints of professionalism, at least in theory, through “third-party government,” which channels relatively inflexible and unresponsive federal programs through local nonprofits. They in turn can be counted on to introduce the flexibility and responsiveness we know to be essential to success. Insofar as federal social programs are effective, chances are they’ve found ways to preserve their flexibility and individually tailored adaptiveness in the face of bureaucratic professionalism’s relentless drive to regulate, rationalize and regiment.

The tyranny of success is reflected not in a ruthless exposure of failure—as many have noted, there’s very little of that. It is reflected, rather, in our denial of failure—in our determined averting of eyes from its omnipresence, our refusal to acknowledge its direct but complex connection to success. The outcomes-oriented among us find ways to strip-mine the “good stories” from frontline nonprofits while leaving behind slag heaps of “bad stories” for them to dwell upon alone, in their difficult hours of self-criticism. We find ways to reap the benefits of deep, often painful personal commitment by frontline leaders without ourselves having to share their suffering. Indeed, we praise ourselves for keeping that suffering at arm’s length through the norms of professionalism. But in rare moments of honesty we confess that those norms must be violated on a regular basis if we are, in fact, to do our work.

Note

- Lisbeth B. Schorr with Daniel Schorr, Within Our Reach: Breaking the Cycle of Disadvantage (New York: Anchor, 1989).

William Schambra is director of the Hudson Institute’s Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal.