Events and social movements of the past three years have spawned many efforts to advance racial justice in philanthropy, as many have written about at NPQ and elsewhere. Headlines were filled with financial commitments from different sectors to racial equity and justice. Many foundations launched racial equity-focused collaboratives and funds. Participatory grantmaking is on the rise, and powerful philanthropic institutions have made public commitments to do better.

Such actions are crucial as philanthropy’s current and historic practices have led to disparities in funding between white-led organizations and organizations led by people of color, reinforcing broader racial inequities. Progress will only be achieved, however, when funders begin measuring resource allocation across white- and BIPOC-led organizations and taking steps to ensure equitable funding.

There are a few things about racial equity in grantmaking that we know for sure:

- Historically, Black- and Brown-led nonprofits have received disproportionately low funding when compared to white-led nonprofits.

- Social impact efforts are more effective when led by individuals who reflect the populations served.

- Measurements of commitments to racial equity vary widely across nonprofit and philanthropic institutions and efforts.

- Organizations across the country lack a shared understanding of the demographics of nonprofit leadership—including their race, sex, gender, sexual orientation, and disability—making baseline comparisons of progress at scale difficult.

- In this context, according to the Center for Effective Philanthropy, 40 percent of foundation leaders have said that they are focusing on improving their demographic data collection.

You can only improve upon what you measure

Measurements of commitments to racial equity vary widely across nonprofit and philanthropic institutions and efforts.

Ensuring that Black and Brown leaders have access to philanthropy’s vast resources is central to funders’ efforts to realize equity in the nonprofit sector. The sector is a vast network of institutions, projects, and programs that provide critical social services throughout the US; today, one social-impact oriented nonprofit exists for every 200 people. Combatting historical and systemic racism in nonprofit funding requires intentionality, and this is where measurement comes into play. The nonprofit sector generally measures progress along a cycle that spans about three to four years. We try out a new program or way of operating, implement it, then look back a few years later to review our successes and failures. We apply the lessons learned to the next three to four years and repeat the cycle.

The problem with this cadence is that the world changes faster than our ability to measure progress, leading to a long trajectory of incremental change.

We must ask, “How are we doing?” several times a year rather than, “How did we do?” once every few years.

When nonprofits and funders practice real-time, data-driven strategy in a way that influences the decisions and behaviors of the people responsible for carrying out a mission, they identify and solve problems much faster. Progress toward a more racially equitable system in both grantmaking and nonprofit program delivery is one area where measuring the results of people’s decisions and behaviors as the work unfolds leads to greater impact much faster.

What does this look like in practice?

When it comes to our nation’s most urgent issues—like reducing racial disparities—nonprofits, government, and philanthropy must accelerate the pace of change. This requires asking different questions about our progress. We must ask, “How are we doing?” several times a year rather than, “How did we do?” once every few years.

In March 2020, Northeast Ohio funders established the Greater Cleveland COVID-19 Rapid Response Fund (GCCRRF), a collaborative that has provided local nonprofits with over $20 million in additional resources through a bi-weekly—or sometimes weekly—grant cycle. Early in the pandemic, it became clear that Black- and Brown-led nonprofits were having the greatest impact in on-the-ground community response. In September 2020, GCCRRF resolved to prioritize racial equity in their funding, which they defined as allocating resources to communities disproportionately affected by the pandemic—specifically Black and Brown communities served by Black- and Brown-led nonprofits.

Step 1: Measuring a commitment to racial equity in grantmaking

To do this, GCCRRF modified their funding application to include questions about the racial demographics of each nonprofit’s leadership (board, executive director, and staff) and the population served. A few months after they started collecting this data, their analysis illuminated two patterns in funding disparities between white-led and Black- and Brown-led organizations:

- White-led organizations were 15 percent more likely to receive funding from GCCRRF than Black- and Brown-led organizations.

- Overall, white-led organizations were awarded 31 percent of their requested grant amount, while Black- and Brown-led organizations received just 19 percent of their requests.

Step 2: Taking action on unconscious bias right away

During an hour-long facilitated discussion, this group created four actionable practices to reduce racial disparities in funding by 1) discontinuing the denial of funding because a program was unknown, new, or unproven; 2) providing more staff salary support for Black- and Brown-led organizations; 3) noting the racial makeup of nonprofit leadership during decision making; and 4) conducting due diligence through additional conversations with Black- and Brown-led organizations’ grant applications to fully understand the potential of their programs.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Step 3: Monitoring key indicators of disparities in funding

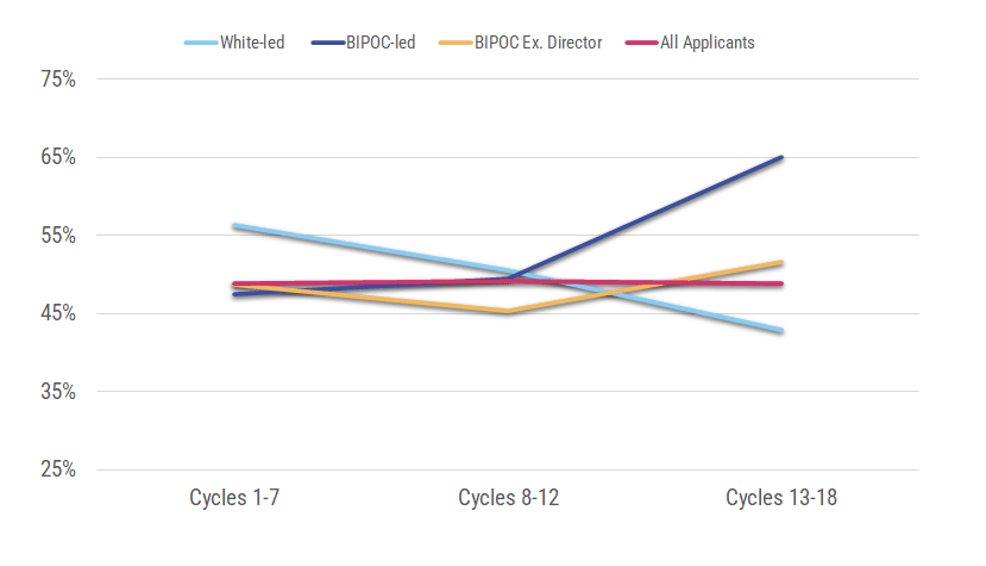

GCCRRF collected and analyzed data to identify how and where disparities could be or were present and decided to track two key indicators during every grant cycle: the funding rate (that is, the rate at which organizations were receiving grants relative to the number of applicants for those grants) and the amount of funds applicants requested compared to the amount of funds awarded. The following chart illustrates changes in funding rates across 18 rapid response grant cycles (over nine months).

Funding Rates: Changes Over Time

In grant cycles one through seven, white-led organizations were funded at a rate of 56 percent, while Black and Brown-led organizations were funded at a rate of only 47 percent. Once GCCRRF’s partners implemented the actionable practices described above, these grantmaking disparities began to close. Within three months of implementation, GCCRRF’s racial disparity in funding allocation between white-led and Black- and Brown-led organizations was eliminated, sending more resources to organizations led by people who represent the populations being served.

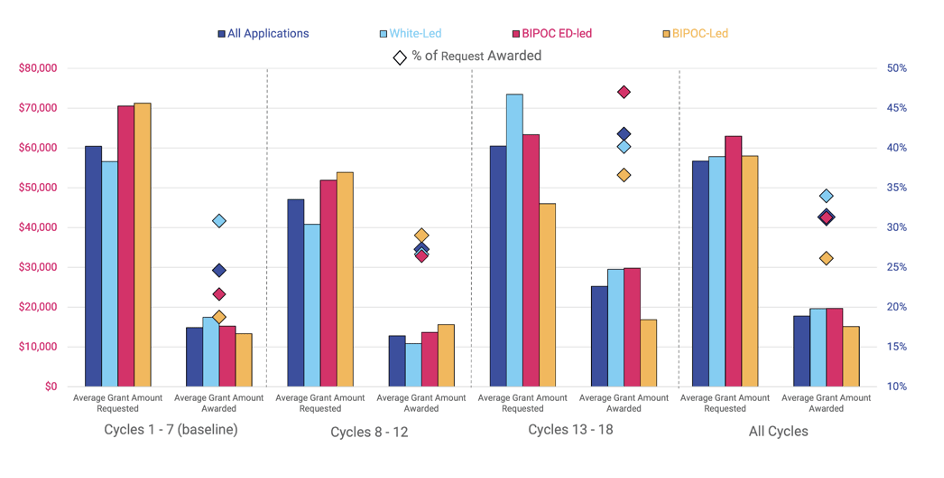

Amount Of Funds Requested Versus Funds Awarded

The preceding chart illustrates changes in the amount (in US dollars) that applicants requested compared to the amount that they were awarded during the 18 grant cycles measured. Each bar illustrates the average grant amount requested by and awarded to each group during a set of cycles. Groups are broken down into white-led, BIPOC-led, and BIPOC ED-led, with a final bar representing all organizational applicants. The diamonds illustrate the average percentage of the requested dollars that was ultimately awarded. In the section of the chart representing grant cycles 1–7, there is a significant gap between the light blue diamond (white-led) and the yellow and pink diamonds (BIPOC-led and BIPOC ED-led, respectively).

By following simple actions to reduce unconscious bias—namely, by collecting data about the racial makeup of funding recipients—GCCRRF eliminated racial disparity in their funding practices within three months of analyzing their data, changing their approach to grantmaking.

Within four months, they began to counteract historic racism in funding practices by awarding Black- and Brown-led nonprofits a greater percentage of total dollars requested than awarded to white-led organizations—a large step toward achieving equitable grantmaking.

Step 4: Realize the impact of a data-driven approach

GCCRRF’s work shows that philanthropy can measure its commitment to equity and use data to close racial disparities. In this case, Black- and Brown-led nonprofits became more likely to receive funding—and more of it. As a direct result of eliminating racial disparity in grantmaking, such organizations saw a 21.5 percent improvement in their likelihood of being funded and an 18 percent increase in the total amount awarded relative to their initial request. A more equitable allocation of resources resulted in about a 20 percent increase in total funds allocated to Black- and Brown-led nonprofits.

This work changed the culture in many of Cleveland’s grantmaking institutions, which likewise began to track and measure their allocation of resources across white-led and Black- and Brown-led nonprofits. “The data helped us examine our assumptions and unconscious biases and adjust our approach. This is one small step of the many we need to take to address inequities in our community,” said Jeanine Gergel, a consultant at Foundation Management Services in Cleveland. By regularly collecting and analyzing their data in this way, Cleveland funders can set tangible benchmarks, meet measurable goals, and build traction towards equitable grantmaking. “Philanthropy should not go back to the way it worked before,” said Dale Anglin, Vice President of Programs at the Cleveland Foundation. “If we’re doing grantmaking three years from now the way we did it three years before, we didn’t learn anything.”

Lessons for the field

GCCRRF’s collaborative work offers many lessons for philanthropic organizations. Looking ahead, funders can:

- Start by measuring their commitment to racial equity in grantmaking. You don’t need to wait for a baseline or all the data in the world—get started by looking at what you are doing now.

- Stop measuring their commitment to racial equity based on the demographics of the populations served by their grantees alone and start measuring the demographics of leadership.

- Implement practices to eliminate unconscious bias in grantmaking by:

- Getting to know Black and Brown nonprofit leaders

- Investing more heavily in operating support for Black- and Brown-led organizations

- Creating a culture that encourages equitable distribution of resources in day-to-day decisions by noting the racial demographics of nonprofit leadership during decision-making conversations with staff and boards.

- Be intentional about establishing key indicators of funding disparities and monitor them every time you make grants. Turn your grants management data into insights by setting up dashboards to automatically calculate and monitor progress while reducing the burden of frequent data analysis.

- Be humble about your shortcomings. Chances are that when you start measuring resource allocation—who’s receiving resources and how much—you are going to find disparities. You can only improve upon what you measure.