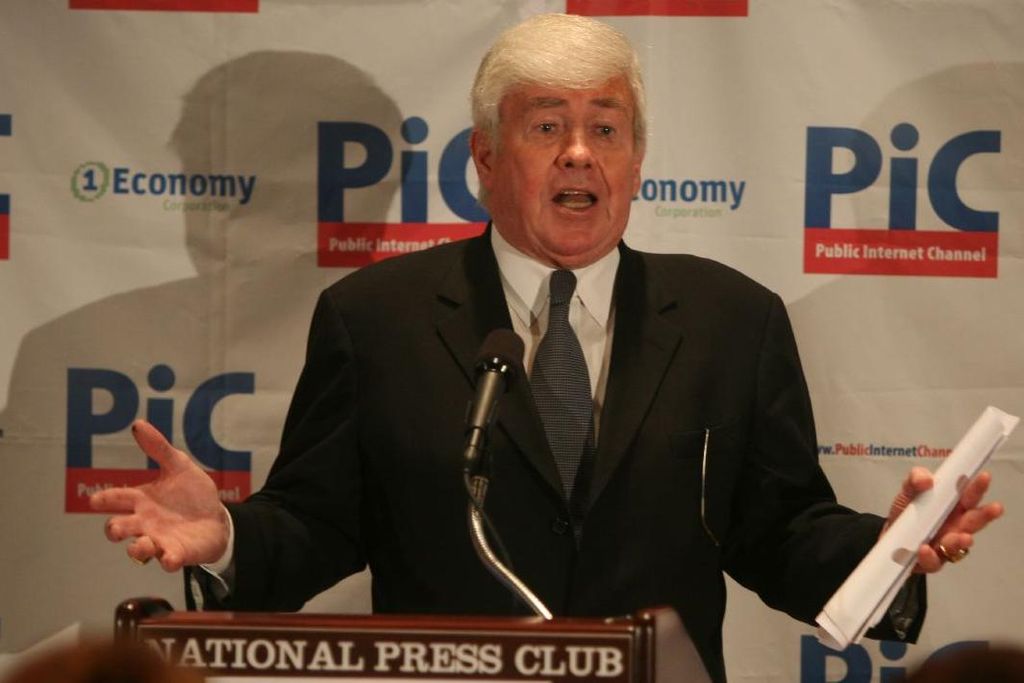

Among conservatives, Bob Woodson stands out as an activist who gets his ideological compatriots to pay attention to issues of poverty. Liberals may not like Woodson’s prescriptions, long articulated by the Washington-based think tank he created decades ago, the Center for Neighborhood Enterprise, but he is authentic in his concern and commitment. Known for mentoring Rep. Paul Ryan on poverty issues, Woodson was also an influential advisor to the late Jack Kemp, the Republican congressman and vice presidential and presidential candidate who most famously for nonprofits served as Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development under President George H.W. Bush.

Woodson and Ryan have now put together a television mini-series called Comeback that “shines the light on the people that Woodson calls ‘community antibodies’…the neighborhoods’ organic defense against threats such as violence, addiction, and social breakdown.” The seven episodes of Comeback are available on the Center’s website, featuring stories about the likes of Greg Bradford, who has gone from drug addiction to opening a shelter in Elyria, Ohio; Omar Jahwar in Dallas, who is recruiting former gang members as role models for youth; Daryl Webster, who runs a 21-day “boot camp” for men in Indianapolis; Shirley Holloway in Washington D.C.’s Anacostia area, who is teaching drug addicts life skills; Jubal Garcia, who is helping former drug addicts assimilate back into the community in San Antonio; and Buster Soaries in Somerset, N.J. who is trying to instill “the values of self-discipline and personal responsibility in order to help people correct destructive life choices.”

Nearly all of the episodes focus on initiatives led by people of religious faith—Soaries, Webster, and Jahwar are ministers, and other programs described in Comeback are in or linked to churches. Many Comeback episodes deal with people who have had to overcome drug addiction. The underlying theme of many of the stories is overcoming personal decisions that have led people into poverty. The notion that there might be systemic issues causing poverty and needing to be eradicated gets less play.

Forbes contributor Jerry Bowyer interviewed Woodson about an interesting connection between him and Ryan, the fact that the miniseries in which Ryan plays a significant role (particularly in the first episode) doesn’t mention Kemp, who was actually a mentor to Ryan as well.

Bowyer senses Kemp’s influence in Comeback, and Woodson agreed, calling the series a “revisit” to the Kemp agenda. Interestingly, despite the emphasis of Comeback on stories overcoming destructive personal choices, Woodson discussed Kemp’s influence in policy terms, including issues of empowerment (Kemp was the prime mover behind the “empowerment zone” concept) and resident management in public housing. Woodson decried, however, the conservative movement’s retreat from “an antipoverty agenda, a real war on poverty, not the one that failed for fifty years” in the wake of Kemp’s departure from government and eventual passing. He added:

“The conservative movement does not seem to understand that there is a lot of discontent in low-income, particularly black neighborhoods, because they know that in the past fifty years of blacks being elected to office, running most of these cities where the policies are failing, and twenty trillion dollars on programs that aid the poor, that they have not benefited. But they have not found a champion to their cause until Paul Ryan came on the scene.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In political or policy settings, Kemp was the leader who kept the conservative movement focused on poverty issues. His passing left political conservatives without a strong champion on issues of poverty. Woodson seems to think that Ryan can pick up that mantle.

However, Woodson continues on a bent that he and Ryan have followed recently, the notion that anti-poverty agencies (or nonprofit human service delivery groups more broadly) “have created a commodity out of poor people.” He suggested that these agencies “want to know which problems are fundable, not which ones are solvable.” He charged that 70 cents on every dollar of poverty spending “goes to the providers, and not directly to cash payments to their recipients,” citing a study of poverty programs in New York City conducted by the “liberal” Community Service Society. That 70 cents on the dollar, however, he noted, goes to “doctors, counselors, drug counselors, and whatnot,” which perhaps Woodson appears to think are classes of people who simply suck poverty money out of the system, but actually provide valuable services for the kinds of people highlighted as beneficiaries of the programs highlighted in Comeback—unless Woodson really thinks that all those “counselors and whatnot” are totally replaceable by members of the ministry.

Woodson and Bowyer agreed that, in Woodson’s words, the anti-poverty system that exists today “injures people with a helping hand.” Woodson acknowledged that “the people and the providers (in the system) are not evil people,” but Bowyer characterized the system itself as evil. Woodson explains, “You got a system where good people are trapped in systems that cause good people to do bad things for the poor.”

Woodson sees a political upside for conservatives to talk about poverty. He suggests that Ryan, as Romney’s vice-presidential running mate, tried to convince the Romney campaign to address poverty but lost out to Romney’s disastrous “47 percent” statement. However, he cites counter-examples such as Dick Riordan, who, as the Republican mayor of Los Angeles during the 1990s, “went into a low-income area of East L.A., a Hispanic community, and he worked with some groups and built the Riordan Center, a state-of-the-art facility.” Riordan’s political successes speak to Woodson’s conclusion that “if you invest charitably, you can harvest politically.” He sees political advantages for conservatives going forward on the issue of poverty, suggesting that minority communities in cities are “disillusioned…[and] unhappy with the leaders they have.” His example is Detroit, which he told Bowyer “has been run by liberal black Democrats for almost forty years. And it looks like Hiroshima did after the war.”

Those of us who know Woodson and the work he has done among warring gangs and in difficult public housing projects find much to admire about the man. But beyond the pale are the hyperbolic statements about money wasted on drug counselors and doctors, the anti-poverty nonprofits that exist only to maintain themselves in business, the myth that the successful programs that have helped people in cities get out of poverty somehow eschew government funding, and that inner city neighborhoods, even the worst of them, look like Hiroshima. Add to this analysis the omission of any systemic factors about jobs, racism, and educational disparities, and the Woodson/Ryan analysis takes anti-poverty strategies into very limited byways.

That Woodson acts a voice among conservatives saying that they need to focus on issues of poverty is a positive, and it is even good that Ryan is issuing papers and strategies within Republican Party circles that address poverty, even though some of us feel the recommendations themselves are exceptionally off-base. But the strategies that Woodson and others address, when built on mythologies about the urban poor, do not lead to solutions that address the millions of Americans who live in poverty. Our recollection of Kemp during his time as HUD secretary is that he understood the intersection of the efforts of dedicated anti-poverty warriors like Woodson with the infrastructure of public policies needed to sustain their programs toward success. That’s the Kemp story that also should be in embedded in the Comeback episodes.—Rick Cohen