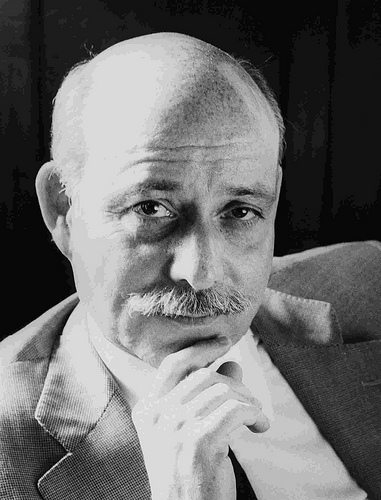

Last Saturday, famed economist and political advisor Jeremy Rifkin was featured in the New York Times in an op-ed entitled “The Rise of Anti-Capitalism.” In it, he predicts that the nonprofit sector will become increasingly important in the world’s economic future as more and more of the way we do business is based on networks and automation and the “Internet of things.” In all of this, he says, the capitalist market will become a “niche player,” providing networking platforms in an increasingly collaborative economy.

This is far from Rifkin’s first such assertion about the primacy of the nonprofit sector. As the conclusion to his The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era (1995), he suggested that the vast majority of workers in the information age would be shoved to the margins of the economy and unless a new path were found, the “workerless society” would be marked by mass unemployment, widespread desperation, and social upheaval. At the time, he was derided for being overly pessimistic and for engaging in technological determinism. He wrote:

“We are entering a new age of global markets and automated production. The road to a near-workerless economy is within sight. Whether that road leads to a safe haven or a terrible abyss will depend on how well civilization prepares for the post-market era that will follow on the heels of the Third Industrial Revolution. The end of work could spell a death sentence for civilization as we have come to know it. The end of work could also signal the beginning of a great social transformation, a rebirth of the human spirit. The future lies in our hands.”

Here is a recent blog post by Robert Charette revisiting Rifkin’s predictions, in case you were wondering about the accuracy of what he foresaw.

Rifkin believed even then that the nonprofit sector was and would be primary because it addressed culture and spirit and cooperative interaction but he charged that the sector inflicted itself or at least accepted an identity that profoundly underestimated its importance and primacy. In a 2001 interview with the Nonprofit Quarterly, Rifkin said,

“We have taken this sector, which is the primary wellspring of human life, and we have marginalized it as if it deserves last place in our social priorities. Think about the language we currently use to describe this sector. In Europe, they call it non-governmental—not quite public, but dependent upon the government. And in the U.S. we colonize toward the commercial arena, so we call it nonprofit—not corporate, but dependent upon the corporate sector. A lot of the way we view ourselves is dependent on metaphors and language—we act out of these metaphors. We should get rid of nonprofit and non-governmental—these are colonial terms and attach us as subsidiary to the secondary institutions of market and government. We are the culture and that is primary.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Rifkin predicted at that time that as there was less need for human capital in production, there would be more interest in and more of a premium put on things that we can only get from and with other humans—things that are tailored, local, of community, and valued-aligned and inspired.

Now, Rifkin appears even more certain that the civil sector or an organized social commons needs to take the lead in the reconstruction of a global economic future. He believes that the future of the economy promises what he terms “an Internet of Things” and “infrastructure that optimizes collaboration, universal access, and inclusion, all of which are critical to the creation of social capital and the ushering in of a sharing economy.”

“The Internet of Things is a game-changing platform that enables an emerging collaborative commons to flourish alongside the capitalist market. This collaborative rather than capitalistic approach is about shared access rather than private ownership. For example, 1.7 million people globally are members of car-sharing services. A recent survey found that the number of vehicles owned by car-sharing participants decreased by half after joining the service, with members preferring access over ownership. Millions of people are using social media sites, redistribution networks, rentals and cooperatives to share not only cars but also homes, clothes, tools, toys and other items at low or near zero marginal cost. The sharing economy had projected revenues of $3.5 billion in 2013.

Nowhere is the zero marginal cost phenomenon having more impact than the labor market, where workerless factories and offices, virtual retailing, and automated logistics and transport networks are becoming more prevalent. Not surprisingly, the new employment opportunities lie in the collaborative commons in fields that tend to be nonprofit and strengthen social infrastructure—education, healthcare, aiding the poor, environmental restoration, child care and care for the elderly, the promotion of the arts and recreation. In the United States, the number of nonprofit organizations grew by approximately 25 percent between 2001 and 2011, from 1.3 million to 1.6 million, compared with profit-making enterprises, which grew by a mere one-half of 1 percent. In the United States, Canada, and Britain, employment in the nonprofit sector currently exceeds 10 percent of the work force.”

Rifkin, however, points again to the image (and, sometimes, the self-image) of the sector “as a a parasite, dependent on government entitlements and private philanthropy.” This image does not, he asserts, meld with reality, and he references a study showing that “approximately 50 percent of the aggregate revenue of the nonprofit sectors of 34 countries comes from fees, while government support accounts for 36 percent of the revenues and private philanthropy for 14 percent.”

NPQ would love to hear readers’ thoughts on Rifkin’s vision. We were surprised, in light of the noise around social enterprise, to not see any discussion of the piece in domestic nonprofit and philanthropic circles to date, though there appears to be more overseas.—Ruth McCambridge