Editors’ note: This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s fall 2016 edition, “The Nonprofit Workforce: Overcoming Obstacles,” and was lightly edited for this publication. It was originally published in Afterschool Matters (no. 22, pp. 24–31), National Institute on Out-of-School Time, Wellesley Centers for Women, Wellesley College, in fall 2015.

Across the United States, youth development approaches are being tested in out-of-school time (OST) programs as a strategy to combat the growing opportunity gap between privileged and underprivileged youth.1 Along with increased recognition of the value of youth development programming has come increased financial support.2 This investment, in turn, brings increased pressure to continually prove to funders that youth development programs affect student outcomes.3 The increased emphasis on accountability has sometimes forced community-based organizations (CBOs) to maintain a myopic focus on outcomes that are easily measurable but not necessarily the most important.4 Underfunded nonprofits can feel overwhelmed by the intense emphasis on producing evidence-based outcomes, especially if evaluation feels like an add-on rather than being aligned with and integrated into program goals.

This article proposes critical participatory action research (critical PAR) and youth participatory evaluation as possible answers to this challenge. Expanding the definition of evaluation to include methodologies that value youth participation can strengthen CBO’s capacity to create responsive OST programs that have meaningful impacts on young people’s lives. This article explores how five programs use critical participatory action research and youth participatory evaluation to engage youth and improve program delivery. These trailblazing organizations illuminate the possibilities and challenges of using approaches to research and evaluation that reflect youth development principles and practices.

Participatory Action Research and Evaluation Approaches

The interdisciplinary and activist history of critical participatory action research stretches back to Kurt Lewin, Paulo Freire, Orlando Fals-Borda, and Mohammad Anisur Rahman.5 The participatory approach braids critical social science, self-determination, and liberatory practice in order to interrupt injustice and build community capacity. Those who practice this youth development–oriented approach bring to their qualitative and quantitative research a commitment to local knowledge and democratic practice.6 Those who are affected by the topic under investigation are essential partners in the research process. Young people conducting participatory action research in partnership with adults engage in ongoing and sometimes overlapping cycles of fact finding, planning, action, and reflection.7 Research teams attempt not only to understand the data but also to use it to alter the underlying causes of the problem at hand.

Youth participatory evaluation emerged in the late 1990s as an extension of the field of participatory evaluation. Pioneers in the burgeoning field pushed to involve young people as stakeholders in program evaluations.8 The past decade has brought elaboration on how youth participatory evaluation happens in youth development settings and the benefits that occur when it does.9 Such benefits include youth leadership10; strong youth–adult partnerships11; and, according to some, more valid and useful research.12

Involving youth in critical participatory action research and evaluation builds on young people’s strengths, expertise, and ability to create knowledge about the issues and programs that affect their lives. Research is conducted with youth, not on them. Young people are viewed as the experts on their own experiences. They are, in this view, completely capable of exploring youth issues and programs—in fact, they are necessary members of the research team.

This perspective is remarkably well aligned with an assets-based youth development approach. The alignment becomes even more evident in the partnerships formed when young people and adults create research about young people’s programs, communities, and experiences. Foundational research in the field of youth development tells us that three major factors in youth development settings foster resilience and enable youth to thrive: caring relationships, high expectations, and opportunities to contribute.13 A framework currently gaining traction in the field has synthesized decades of research evidence, practice wisdom, and theory to posit that children learn through developmental experiences that combine action and reflection, ideally in the context of caring, trusting relationships with adults.14 The cycles of action and reflection of participatory action research, undertaken in respectful partnership with adults, create ideal conditions for development.

Knowledge production in partnership with young people operates at the intersection of youth development and youth rights.15 This crossroads may feel quite comfortable to youth-serving organizations committed to the struggle for equity on behalf of and in partnership with young people. However, though some innovators are engaging in participatory action research in and out of school, the potential for engaging youth in participatory evaluation in OST programs is largely untapped.16

Research Design

To uncover the benefits and challenges of engaging youth in participatory evaluation approaches, we studied the experience of staff from five CBOs who attended the five-day Critical Participatory Action Research Institute (CPAR Institute) hosted by the Public Science Project in summer of 2012. The Public Science Project has a fifteen-year history of involving youth as researchers, facilitating vibrant research camps and large-scale youth research projects on issues ranging from policing practices to educational equity. It acts as a hub for scholars of critical PAR and a training institute for those looking to implement participatory methods in their own contexts.17 Our five case-study CBOs (we will call them CBO 1 through 5) all followed up on their learning at the institute by incorporating participatory evaluation in their programs.

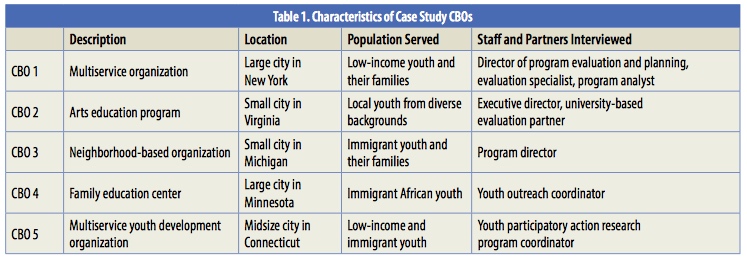

Of the forty-five participants in the 2012 CPAR Institute, seventeen were from CBOs or university–CBO partnerships. We invited those who worked in OST and who wanted to engage youth in action research to participate in our study. Eight staff members from five organizations agreed. The five CBOs varied in size, location, and program focus, as summarized in Table 1.

We conducted semistructured interviews with the eight CBO staff members before they participated in the CPAR Institute. During the staff members’ participation, in June 2012, we conducted ethnographic participant observations. Right after their participation, we facilitated a focus group with seven of the staff members, representing all five CBOs. We conducted follow-up interviews three to four months after their participation, in fall 2012, reaching six staff members from four of the organizations. Interviews and focus groups were recorded and then transcribed. We analyzed the data using a methodology based in grounded theory.18

Moving Participatory Evaluation from Theory to Practice

The study participants emphasized that they brought youth-centered and strength-based approaches with them to the CPAR Institute, stressing the role of sports, the arts, culture, families, and civic engagement. However, only two of the five organizations had previously used participatory approaches to teaching and learning, and only one had engaged in participatory research. In the follow-up interviews a few months after their participation, all reported having used participatory strategies in program implementation, design, or evaluation.

One study participant had incorporated a full participatory action research project into her CBO’s youth summer employment program. The project engaged a team of ten youth in researching young people’s experiences of schooling. The participant, a youth outreach coordinator at CBO 4, outlined the process in her follow-up interview:

We all worked together for twenty-five hours a week for five weeks. We started off with a research camp kind of curriculum, combined with some curriculum on anti-oppression, work on sexism, racism, things like that.… We did school mapping…with some guided questions, and one was, “Where do you feel least safe or where do you feel most safe?” [We] prepped [research camp participants] a lot on interviews. They also interviewed each other a lot to home in on what our first round of interview questions would be.

This intensive first experience with participatory action research brought both challenges and benefits to the organization, as we will discuss below. By a few months after participation in the CPAR Institute, the other four organizations in the study had carried out less intensive but equally innovative attempts at incorporating the approach into their practice. Strategies they used with youth included research camps, mapping exercises, interviews, surveys, critical conversations, and performances or presentations of research findings by youth.

Benefits of Participatory Evaluation

The follow-up interviews revealed four benefits of engaging in research and evaluation processes aligned with the principles of youth development:

- Increased youth engagement and leadership;

- Deeper adult–youth partnerships;

- Increase in participatory practices across the organization; and

- Improved quality of the research.

Youth Engagement and Leadership

Follow-up interviews revealed that even CBO staff who were already committed to youth leadership were impressed by the effects of critical participatory action research. They saw co-construction of knowledge through research as an effective way to build young people’s confidence. For example, the interviewee from CBO 5 said the following about the approach:

[It] is very effective at building leadership. My students—in particular several that had for a long time, as far as I can tell, been labeled “unsuccessful” in the classroom and schools, and [were] at various levels of marginalization in school—really turned a corner.… [T]hey were able to feel successful in this learning environment we created together, where their knowledge, questions, and opinions were so valued.

This interviewee believed that taking part in critical participatory action research in the OST program built students’ confidence in the academic realm, as well.

Adult–Youth Partnerships

In follow-up interviews, study participants described how engaging in participatory action research brought changes in the dynamics between young people and adults. Awareness of how adults and youth can share power led to more intentionality about who took on the evaluation tasks, both large and small—from defining a project’s research questions to summarizing the data gathered. A staff member from CBO 1 described how this new awareness informed a project in which a team of youth and adult researchers explored the meaning of youth success:

We were very much focused on always being mindful of our relationship with the participants, and on the first day we began with a very broad question about what is research and who is a researcher.… We were very explicit about opportunities for participation, always looking for ways the young people could [participate]…or anything that we could do to get away from [the adults doing the] talking.…We had one piece where we had identified five subthemes of success we wanted to zero in on, but we had a list of twenty and we gave everyone five stars and they voted.… We would have previously done show of hands, but we did it like that so everyone would have a voice.

Study respondents spoke about how engaging youth in participatory evaluation enabled them not only to relinquish control but also to collaborate with young people and engage them as both teachers and learners. Some participants, including the program director of CBO 3, said that the CPAR Institute enhanced their commitment to viewing young people as assets: “[CPAR] for me has…enhanced my belief [that youth] are a source of amazing information and that, when we listen, we find out so much.”

For program directors, working as full partners with youth and their communities involved questioning their traditional approach to building “clear boundaries” between staff and community members. As a respondent from CBO 1 put it, a participatory approach can clash with the traditional notion that “staff [must] have very clear boundaries, so they are not friends, they don’t fraternize.” In the focus group, several staff members agreed that boundaries can serve as a means of demonstrating “who is in charge” in a youth program. However, they also agreed that boundaries helped staff members feel safe working with youth and their communities. Organizations that incorporate participatory evaluation may need to reflect on ways to balance the necessity for healthy boundaries with the benefits of open communication and mutual trust.

Participatory Approaches across the Organization

A third theme in the interviews was that participatory approaches offered benefits not just for the OST program and its youth and staff but also for the entire CBO. Even when the task at hand was not research, respondents said, they had become more comfortable with letting young people take the lead. Participatory practices and sharing leadership with young people were described by one participant as a “PAR-esque” approach that was seeping into his CBO’s culture.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The evaluation director of CBO 1 reported that having integrated youth into critical participatory action research was affecting work with the staff:

We introduced icebreakers into program meetings, just to chill people out. And then we realized that the icebreakers we were using were really about establishing common ground, so that we would, for instance, have a meeting with the afterschool staff, and the icebreaker was, “Tell us about your first involvement with afterschool.” […] So we all kind of established our stake and that we were all stakeholders in afterschool programs with a lot of commitment to them and perspective. [W]e really have developed this process in these meetings about power relations and establishing common ground and common purpose.

Organizations that incorporate a participatory frame into youth-centered and strengths-based approaches may experience benefits across the entire organization, not just with the youth.

Quality of the Research

A fourth benefit the CBO respondents noted was that the quality of their research improved. CBO staff were committed to participatory practices not only out of idealism but also because these practices better equipped them to carry out valid research. One respondent mentioned that collaboration with youth on an evaluation survey brought up issues “that would have never come to mind” for the adult staff members. The program coordinator from CBO 5 put it this way:

A PAR approach has definitely taught me that people who are “the subjects” of the research need to be in the room from the first, including designing what the research questions have to be. I learned that really early on…when we interviewed youth to hire them and we created our questions about school.… And they all talked about favoritism. And that, to me, was a great lesson, because if I had designed the interview questions about youth experience, [I] never would have asked about favoritism.

Challenges of Participatory Evaluation

In addition to benefits, the follow-up interviews revealed challenges in involving youth in participatory action research and evaluation. A major challenge is that these approaches take time. One CBO staff member articulated a common issue: feeling torn between being realistic about the workload and being committed to a participatory approach:

I am very happy with the way [the project] turned out, but it was also a reality check because it took a lot of our time. And I am here thinking I would not want to do this again until next summer because I have so many other projects on my plate.

The youth outreach coordinator from CBO 4 echoed this sentiment, explaining that the budget and design of her program did not allow for the level of youth participation that would have produced high-quality data. The five weeks allotted for research did not allow the youth to take part in designing data collection instruments, conducting the research, and analyzing the data. This staff member struggled with how much she and the other facilitators should structure the work ahead of time and how much to leave open for the adult–youth team to shape together. She compromised by starting the process with a well-defined topic for the project and with structured workshops that helped the research team come alive. Once the team had agreed on a subtopic and method for the projects, she provided scaffolding and assistance to help the youth complete their goals in the available time.

A second challenge was lack of institutionalization of participatory approaches to program design and evaluation. The executive director of CBO 2 explained:

I definitely feel reluctant [about] our kids having to fill out tons of tests like rats in a maze and [about putting] them through pre- and post-tests. Honestly, we run on an extremely skinny budget, and we don’t have the administrative capacity to administer pre- and post-tests or evaluate them or administer the data.… Not to say we don’t want to demonstrate the impact of our program to people, but I am just concerned that funders and foundations are going over the top in creating really unrealistic requirements [for organizations] such as ours, which will be at risk of going out of business because of these requirements. And I think CPAR can perhaps provide tools that are more user-friendly and friendly to the population and that are not viewed punitively.

Clearly, this interviewee understands the importance of evaluations that demonstrate program impact. At the same time, the comments reflect a feeling shared by other interviewees that certain approaches to evaluation have negative connotations for CBO staff. This executive director articulates the possibility that youth critical action research can contribute to evaluation that is “more user-friendly” and that, rather than punishing CBOs through funding cuts, can promote a culture of accountability and constant improvement.

Interviewees explained that the transition from providing a one-off participatory project or class to making participatory evaluation a permanent fixture in the organization was difficult. Surprisingly, the interviews revealed hopefulness about the coexistence of outcomes-driven evaluation and critical participatory action research. Respondents felt that their CBOs and funders might be more open than they had thought to participatory program design and evaluation.

Evaluation Aligned with Program Goals

The New York–based multiservice organization whose evaluation staff attended the CPAR Institute saw its evaluation culture positively affected by the inclusion of youth perspectives. One benefit reported by this organization’s study participants was that program staff took a more active role in the design of evaluation strategies, rather than viewing the evaluation staff as the sole experts. As a result, the evaluation process was enriched by expertise of staff who knew the day-to-day operation of the programs and who had direct contact with youth.

A conversation among focus group participants echoed the idea that using critical participatory action research shifted the culture of evaluation in their organizations:

Participant A: It certainly provided a whole new avenue for how we can make [the evaluation] process more friendly to the participants and align ourselves more with them in ways that engage them and…bring them into a process that demonstrates to them the additional talents they have to help provide insight into why or why not the program is working and improve it.… I think [PAR is] a much improved way of trying to help the entire situation of having to do so much more evaluation these days.

Participant B: I think I am very used to the scientific method approach where you go in with a hypothesis. So doing research this way is kind of foreign to me. PAR has made it clear—it is a much more valid form. I always thought so, but until you really see it and really learn about it, it is kind of foreign.

Participant A: [The CPAR Institute] has helped me to see that [evaluation] can be a very empowering tool versus a very overpowering or dominating, exploitative tool.

This dialogue envisions a scenario in which afterschool program evaluation not only accounts for outcomes such as credits gained but also creates space for youth action research projects that influence people and programs. In this youth development approach to evaluation and research, study participants saw a tool that could both build young people’s talents and reveal insights to enable program improvement.

Our study suggests that, in order to experience these benefits, CBOs need to provide institutional support for participatory approaches to design and evaluation. Staff also need to identify the spaces in the organization and its programs where such approaches will be a good fit. Staff from both of the sites that had finished action research projects at the time of the follow-up interview (CBOs 1 and 2) said that their executive directors were open to and supported participatory evaluation. A staffer from CBO 1 described how one program in the organization was open to participatory research, while another was rigidly bound to a different approach to evaluation:

The project in the Bronx received lots of support from the highest levels here. This was included in a packet to one of our major funders this morning, and they were very happy with our organization for promoting youth voice.…On the other hand, we have a lot of pressures going on right now with our child welfare program and evidence-based models.

CBO 2, the other site that had completed a youth action research project at the time of the follow-up interview, also reported that the work was “pretty well received” in the city’s youth affairs agency. This staff member stated that the project “brought a louder voice back to [the] youth affairs [agency] about the necessity of having more youth involvement at every layer of the organization, having more youth involved in planning [the] programs.” This respondent expressed some frustration that grant applications reinforce top-down hierarchies in youth–adult relationships by, for example, not allowing applicants to identify young people simply as “co-researchers.” However, this respondent said, “The foundation we are applying to thinks differently about, and is open in their perspective on, hierarchies in youth–adult collaborations.”

The CBO program and evaluation staff in our study saw critical PAR as a useful and valid tool. In a funder climate that emphasizes evaluation, the alignment of participatory research with an assets-based approach seems to be attractive to executive directors and evaluation staff who are looking to produce useful and valid data while also developing capacities among staff members and youth. Unlike evaluation processes that are perceived as add-ons or resource drains, youth participatory action research adds value by aligning with and expanding on program goals.

Unleashing a Virtuous Cycle

The youth programs featured in this article highlight the power and potential of using research and evaluation designs that are aligned with positive youth development. These sites have found that involving youth in critical PAR can create valid data to drive programs while promoting practices that youth and adults find “user-friendly” and “empowering.” Participatory approaches offer CBOs a way to develop research about youth programs that is driven by the youth and communities most affected.

While it is not without challenges, participatory action research offers benefits, including increased youth engagement and leadership, deeper adult–youth partnerships, an increase in participatory practices across the organization, and greater validity in the research instruments and analyses used for evaluation. These benefits reinforce conditions that enable young people to thrive: partnerships with adults characterized by caring and trusting relationships, high expectations, and multiple opportunities for both generations to contribute to cycles of reflection and action. The study thus suggests that using an evaluation framework that is aligned with the principles of youth development unleashes a virtuous cycle: the evaluative process supports the very outcomes youth development programs are designed to achieve. Though our findings hint at the existence of this virtuous cycle, its process and its implications for program design, implementation, and evaluation must be revealed by further research.

To unleash this virtuous cycle more often, funders need to make an explicit commitment to a youth development approach to research and evaluation. Our interviewees said that their funders and administrators expressed interest in and support for youth involvement in research and evaluation. Though this finding is promising, funders and leaders still need to let youth program staff know that participatory approaches are not only permitted but also valued. Programs need additional funding to support the time and effort it takes to carry out participatory evaluation driven by deep youth–adult partnerships. Similarly, capacity-building support is necessary if our field is to shift the current culture of evaluation to one better aligned with youth development principles and practices.

Increasing funding and building capacity for youth participation in action research will help to institutionalize evaluation approaches aligned with youth development. Capitalizing on these approaches could prove to be a win-win scenario for funders and youth programs that are striving to maximize their impact, shrink the pervasive opportunity gap, and increase youth engagement every step of the way.

Notes

- Margo Gardner, Jodie L. Roth, and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, “Can After-School Programs Help Level the Playing Field for Disadvantaged Youth?” Equity Matters: Research Review 4 (October 2009).

- Heather Clapp Padgette, Finding Funding: A Guide to Federal Sources for Out-of-School Time and Community School Initiatives, rev. ed. (Washington, DC: The Finance Project, 2003); and Sarah Zeller-Berkman, “Critical development? Using a critical theory lens to examine the current role of evaluation in the youth development field,” New Directions for Evaluation 2010, no. 127 (Autumn 2010): 35–44.

- Zeller-Berkman, “Critical development? Using a critical theory lens to examine the current role of evaluation in the youth development field,” New Directions for Evaluation 2010, no. 127.

- Dana Fusco, Anne Lawrence, Susan Matloff-Nieves, and Esteban Ramos, “The Accordion Effect: Is Quality in Afterschool Getting the Squeeze?” Journal of Youth Development 8, no. 2 (2013): 4–14.

- Kurt Lewin, “Action Research and Minority Problems,” Journal of Social Issues 2, no. 4 (November 1946): 34–46; Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (New York: Continuum, 1970); Orlando Fals-Borda, “Investigating reality in order to transform it: The Colombian experience,” Dialectical Anthropology 4, no. 1 (March 1979): 33–55; and Mohammad Anisur Rahman and Orlando Fals-Borda, “A Self-Review of PAR,” in Action and Knowledge: Breaking the Monopoly with Participatory-Action Research, ed. Orlando Fals-Borda and Mohammad Anisur Rahman (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1991): 24–34.

- Orlando Fals-Borda, “Participatory Action Research in Colombia: Some Personal Feelings,” in Participatory Action Research: International Contexts and Consequences, ed. Robin McTaggart (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997): 107–12; María Elena Torre et al., “Critical Participatory Action Research as Public Science,” in APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Volume 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, ed. Harris Cooper et al. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2012): 171–84; and Sarah Zeller-Berkman, “Lineages: A Past, Present, and Future of Participatory Action Research,” in The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, ed. Patricia Leavy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014): 518–32.

- Lewin, “Action Research and Minority Problems.”

- Barry Checkoway and Katie Richards-Schuster, “Youth Participation in Community Evaluation Research,” American Journal for Evaluation 24, no. 1 (March 2003): 21–33; Kim Sabo, “A Vygotskian Perspective on Youth Participatory Evaluation,” New Directions in Evaluation 98 (Summer 2003): 13–24.

- Kim Sabo Flores, Youth Participatory Evaluation: Strategies for Engaging Young People (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2008).

- Linda Camino, “Pitfalls and promising practices of youth–adult partnerships: An evaluator’s reflections,” Journal of Community Psychology 33, no. 1 (January 2005): 75–85.

- Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development, Reflect and Improve: A Tool Kit for Engaging Youth and Adults as Partners in Program Evaluation (Takoma Park, MD: Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development, 2005).

- Matthew Calvert, Shepherd Zeldin, and Amy Weisenbach, “Youth Involvement for Community, Organizational and Youth Development: Directions for Research, Evaluation, and Practice” (Takoma Park, MD: Human Development and Family Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development/Tides Center, 2002); Silvia Golombek, ed., What Works in Youth Participation: Case Studies from Around the World (Baltimore: International Youth Foundation, 2002); and Sabo Flores, Youth Participatory Evaluation.

- Bonnie Benard, Fostering Resiliency in Kids: Protective Factors in the Family, School, and Community, Western Center for Drug-Free Schools and Communities, 1991.

- Jenny Nagaoka et al., with David W. Johnson et al., Foundations for Young Adult Success: A Developmental Framework (Chicago: University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, June 2015).

- Sabo, “A Vygotskian Perspective on Youth Participatory Evaluation.”

- Caitlin Cahill, “Defying gravity? Raising consciousness through collective research,” Children’s Geographies 2, no. 2 (2004): 273–86; Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion, Julio Cammarota and Michelle Fine, eds. (New York: Routledge, 2008); and Ben Kirshner, “Apprenticeship Learning in Youth Activism,” in Beyond Resistance! Youth Activism and Community Change: New Democratic Possibilities for Practice and Policy for America’s Youth, ed. Shawn Ginwright, Pedro Noguera, and Julio Cammarota (New York: Routledge, 2006): 37–57.

- María Elena Torre et al., “Critical Participatory Action Research as Public Science”; and Zeller-Berkman, “Lineages: A Past, Present, and Future of Participatory Action Research.”

- Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin, “Grounded Theory Methodology: An Overview,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, ed. Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1994): 273–85.