This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s fall 2017 edition, “The Changing Skyline of U.S. Giving.”

Giving intermediaries are nothing new, and include a range of vehicles such as workplace campaigns (like the United Way and the Combined Federal Campaign) and community foundation general funds. Of late, such giving intermediaries have found their donors less willing to give into a general fund—where others make decisions about the final destinations of their gift—and more in favor of maintaining decision-making control in a donor-directed grant or donor-advised fund (DAF) within these intermediaries, and in the commercial charitable funds at financial institutions. This article addresses several concerns that have been raised about DAFs and other philanthropic intermediaries, and explores in particular how the growth of DAFs affects the flow of money to nonprofits. Accompanying sidebars explore in short form other influences on the flow and the accuracy of how charitable money is counted.

DAFs: For Better or for Worse?

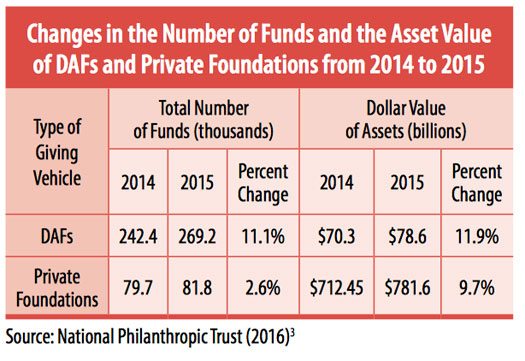

Donor-advised funds are becoming more common and an important philanthropic tool by every measure. For example, as the table below shows, between 2014 and 2015 both the number of DAFs and the dollar value of DAFs grew faster than that of private foundations.1 Moreover, the DAF asset values more than doubled between 2010 ($33.6 billion) and 2015 ($78.6 billion).2

DAFs enable donors to adjust their giving annually to match what they perceive to be the greatest philanthropic needs and those that best match their philanthropic interests. Some fundraisers oppose DAFs because they would prefer that the gifts going to DAFs be given instead directly to the charities for which they raise the funds or consult. Fundraisers have also expressed concern that DAFs allow individuals to be private about their gifts and remain anonymous if they so choose. This anonymity, fundraisers protest, makes it more difficult or even impossible in some cases for fundraisers to steward gifts and to solicit new gifts from donors, unless the fundraisers have a prior relationship with them. On the other hand, this same flexibility may be one of the reasons that DAFs have boomed. Sometimes donors don’t want to be cultivated by recipient organizations and/or by other organizations that may see one gift from an individual via a DAF (or otherwise) and determine that the same individual might also be a prospective donor to their organization. Finally, for various reasons, donors may not want their children, other relatives, or friends to know about their philanthropy.

Some fundraisers find the technological changes to the medium of fundraising frustrating. Most fundraisers would agree that donors connect with the message via the delivery medium—and, theoretically, technological change has made it possible for more donors to connect to a message than ever before—but changes to the medium of fundraising have brought about concerns reflecting a Schumpeterian orientation toward technological change, innovation, and revolutions. (Joseph Shumpeter wrote about the “creative destruction” of technological change in capitalistic economies, for example.)4 As technology evolves and enables some philanthropic transactions to transpire differently from how they have in the past, this will cause some fragmentation of traditional fundraising roles and the role of those relationships in philanthropic flows.

Are DAFs Net New Money, or a Reallocation, or Something Else?

Among the questions swirling around DAFs are those pertaining to whether or not DAFs represent net new money coming into philanthropy or whether they are simply a reallocation of giving that would have occurred anyway.

Giving as a share of GDP has increased slowly over the last forty years. It was very steady from 1976 to 1996, ranging between 1.6 and 1.8 percent.5 During the last twenty years, it has bumped up by approximately 0.3 percentage points and has been steadily in the 1.9 to 2.1 percent range.6 This does not demonstrate that the rise of DAFs has increased giving as a share of GDP, but it suggests that DAFs have not caused total giving to decline in absolute or relative terms.

Given that DAFs are strictly a part of household giving, perhaps a more relevant benchmark is total household giving as a share of disposable personal income (DPI). This picture is more ambivalent. Personal giving as a share of DPI over the last forty years has been between 1.9 and 2.1 percent nearly every year, with the exception of the decade preceding the Great Recession, when this ratio was in the neighborhood of 2.2 to 2.4 percent most years.7 Given that these two ratios (total giving as a share of total GDP and total household giving as a share of DPI) have been either steady or increasing over the last forty years, and given that DPI and GDP have both grown dramatically even in inflation-adjusted dollars over that same time period, we cannot prove (but it seems apparent) that DAFs did not cause a decrease in either total or household giving in either absolute dollar terms or as a share of the economy overall or of personal income.

That said, DAFs could have led to a reallocation of giving that might have transpired regardless. For example, the “uses” categories from Giving USA’s annual report on philanthropy (as seen in the table below) shows that on an average annual growth rate basis, giving to public society benefit (PSB) at 4.0 percent per year (on average) has grown faster than most other subsectors over the last forty years (religion, 1.8 percent; education, 3.5 percent; human services, 2.6 percent; health, 1.9 percent; arts/culture, 2.6 percent).8 However, PSB has grown more slowly (on an annualized basis for the years available) than gifts to foundations (5.2 percent), international affairs (6.9 percent), and environment/animals (5.3 percent).9 It is important to note that PSB is a combination of giving to all sorts of federated funds, including commercial DAFs, Jewish federations, United Ways, and the Combined Federal Campaign (the U.S. government’s campaign, which is similar in many ways to a United Way campaign). And, keep in mind that gifts to DAFs at a community foundation are counted by Giving USA as gifts to foundations, and gifts to DAFs at individual nonprofits are counted in the applicable category of nonprofits. For example, a gift to a DAF at the Indiana University Foundation is counted in the gifts to education category.10

Why Are DAFs So Popular?

One of the questions that is untestable is why DAFs are so popular now. There are at least three functional reasons that make DAFs increasingly popular in our current economic and philanthropic markets.

- Liquidity moments and timing. Oftentimes, a liquidity event (whether triggered, for example, by an inheritance or the sale of a business) happens quickly, with many concomitant planning aspects or details to be addressed. Therefore, making a decision to make a permanent commitment to philanthropy (whether a percentage share of an asset, proceeds, inheritance, etc., or a fixed dollar amount) is more likely and easier to make than to determine exactly how much to give to exactly which charities all at once and all quickly. This seems to be even more the case in an environment that is rapidly and/ or unexpectedly changing for the donor.

- After-tax effects and ease of donating now. With DAFs, donors can donate appreciated stocks or other assets and not pay capital gains taxes. While donors can do the same thing with many charities, not all charities are equipped to accept such gifts, and donors may not be able to easily parcel out partial elements of the appreciated assets to all of the charities to which they want to donate—even assuming that they know to which charities they wish to donate at that time. DAFs make it easy to make a philanthropic commitment now, take advantage of the tax deductions now, and then determine the “who, what, where, when, and why” of giving to specific charities later, as time permits.

- Anonymity. DAFs permit donors to be as public or as anonymous as they wish and to vary that approach from gift to gift. Donors have told me that there are times when they don’t want their children, or neighbors, or colleagues, or fundraisers to know that they are giving to a particular cause, or that they have “that much money to give away” to any cause. One can imagine that these factors coalesce for anonymous giving in many cases, yet DAFs also enable donors to be identified when they wish or when the charity convinces the donor that it is imperative that they be named in order to help raise more money from other prospective donors.

Are DAFs Enabling Donors to “Park Their Money”? Do We Need a Minimum Payout Rate for DAFs?

One argument offered in opposition to DAFs is that they allow donors to just “park their money.”11 However, there appears to be little substantive evidence to support this claim. While the assets of DAFs have more than doubled over the last five years for which data is readily available, the dollar value of grants made from DAFs has also more than doubled, from $7.2 billion in 2010 to $14.5 billion in 2015.12

For better or worse, DAFs have received lots of interest from donors, charities, fundraisers, commentators, and some politicians. Former Congressman David Camp (R-MI) introduced legislation that would have required DAFs to distribute every dollar donated to them within five years of receipt. Failure to do so would have resulted in an excise tax of 20 percent of the undistributed amount. This legislation would have imposed these requirements at the individual gift level—not for all DAFs in aggregate at any one commercial or nonprofit entity overall. Requiring this at the individual gift level would make administration and compliance much more difficult for all parties.

The payout rates of DAFs have been defined in a range of manners (see Giving USA 2017, “Special Section on DAFs” delineating four options that have been suggested by others), but research shows that they all substantially exceed those of private foundations.13 To make the closest thing to an “apples-to-apples” comparison, using the same protocol that foundations use in calculating their payout rates (grant dollars divided by charitable assets at the end of the prior year multiplied by 100 to get a percentage), the National Philanthropic Trust estimates that the payout rate for DAFs was 20.7 percent in 2015 and has been above 20 percent for several years. Moreover, the payout rates for DAFs don’t include their operating costs in their payout rates, which private foundations are allowed to include in their 5 percent minimum payout rate.14 This is often between 0.5 percent and 1.0 percent of the asset value, constituting a nontrivial portion of the foundation payout rate.

This is not to say that DAFs are better (or worse) than private foundations, and they can be similar and different in important ways—but the endless clamor for minimum payout requirements for DAFs is comparable to the political posturing that colleges ought to be bigger (more access), better (more quality), and cheaper (lower price). These are contradictory goals. Foundations are required to pay out a minimum of 5 percent of their prior year’s asset base (simplifying here, though essentially accurate, but foundations can use a rolling multiyear average); however, they are allowed to pay out much more than that. With a few notable exceptions of spend-down foundations (see sidebar, right), the vast majority of foundations’ assets are paid out at the 5 percent minimum rate (plus or minus a point). A requirement of a minimum payout rate for DAFs likely would ossify the minimum into a new maximum as well—essentially causing, in other words, a new standard of minimal compliance.

Which Is Better? Spend-Down vs. Permanent Endowments

From the perspective of getting cash directly in the hands of charities doing frontline work, it is by definition the case that spend-downs would be better than permanent endowments. However, that is not the only criterion to be evaluated in this decision-making process. In the debate around payout rates of foundations (and spend-downs are simply paying out at a much higher rate than permanent foundations), Akash Deep, Peter Frumkin, Renee Irvin, Stefan Toepler, and many others have argued that it comes down to intergenerational equity issues: Do we expect greater needs or greater resources now or in the future? Which strategy would “solve” societal problems faster: more money now or a more continuous stream of resources over time and across generations?15 While admittedly a self-selected sample, a December 2016 report from the Center for Effective Philanthropy indicates that only 16 percent of the foundation CEOs surveyed believe that spending down assets was a promising strategy.16

While most foundations intend to operate in perpetuity, research by the Bridgespan Group (2010) indicated at that time that spend-down foundations were on the rise.17 There are certainly a number of high-profile large institutions that are spend-downs (or plan to become one):

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation will exhaust all its assets within two decades of the death of the last of the three founders.

- Atlantic Philanthropies ended their active grantmaking in 2016 and plan to spend down completely within the next few years.

- The Quixote Foundation made its last grant in 2017.

- The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, the Raikes Foundation, and the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation and the Stephen Bechtel Fund have all opted to spend down their endowments.

Unfortunately, we will only know with a large lag whether it is better for the spend-downs to make a few big bets now or if they would have had more impact by spending more money (cumulatively) over more years. Even then, the historians will only be able to speculate about the potential differences in outcomes in these hypothetical but parallel universes. That said, there is a strong argument to be made that diversity in giving opportunities and giving structures is a good thing for the entire sector; there are benefits to both approaches, and more options allow people to donate more reflectively in line with their interests and values.

Spend-Down Foundation Resources

- Veronica Dagher, “The Rise of Spend-Down Philanthropy: More Philanthropists Give Away Their Foundation’s Assets in Their Lifetimes,” Wall Street Journal, April 13, 2014.

- “Literature Review on Time-Limited Philanthropy,” Duke Sanford Center for Strategic Philanthropy & Civil Society, July 13, 2015.

Payout rates for foundations could be higher than they are currently with little likelihood of the foundations closing entirely. However, based on ten thousand microsimulations for each tested payout rate over the next fifty and/ or one hundred years, foundations most likely would experience a significant decline in the size of their initial corpus if the payout rates were increased.18 With respect to DAFs and the establishment of a minimum payout rate, all I can say is to be careful what you wish for! We have a parallel and clear case with private foundations that the establishment of a minimum payout rate also created a de facto maximum payout rate—at the minimum rate.

DAFs and Double Counting

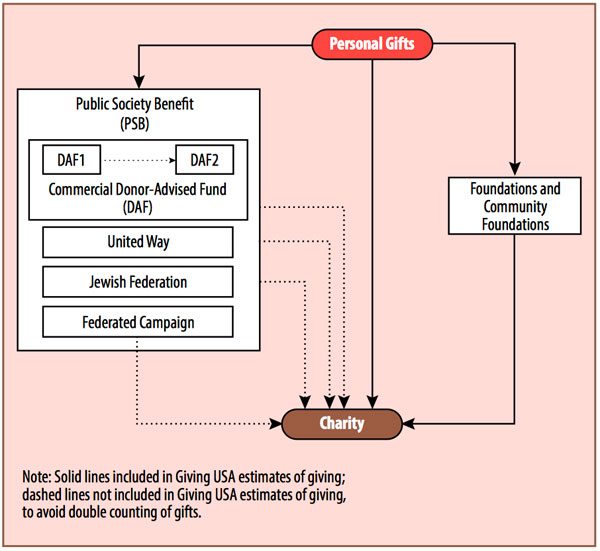

Some have raised concerns about whether DAF gifts are double counted. This stems from the fact that a donation that originally was made to a DAF could be counted once the gift was made to the DAF and again when the disbursement from the DAF was made to a charity. A recent article by Alan Cantor in the Chronicle of Philanthropy has also discussed the possibility of double counting when an individual moves a DAF fund from one commercial entity to another to take advantage of lower service fees, higher annual yields, or real or perceived differences in service levels.19 These dollars are technically a grant from one DAF to another. Cantor speculates that these behaviors exaggerate the payout rates by DAFs.

In the Giving USA report estimates that the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy prepares, we take special steps to ensure that we do not double count gifts. Donor-advised funds are only counted as sources of giving if they are housed in community foundations—otherwise, we do not count grantmaking from donor-advised funds in our sources calculations. On the sources side, giving a donor-advised fund is counted the same way that other individual giving is counted: it is in our giving by individuals estimate.

Giving to donor-advised funds is counted in the Giving USA reports’ “uses” of giving subsectors, but in different ways, depending on where the DAF is housed. It’s important to keep in mind that there are different types of donor-advised fund sponsors, and this impacts where they are counted in the “uses” subsectors. The different sponsor types are counted in the following ways:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Giving to national donor-advised funds is counted in public society benefit (PSB).

- Giving to donor-advised funds in community foundations is counted in giving to

- Giving to a donor-advised fund housed in an individual single-issue charity is counted wherever that charity is located in terms of nonprofit subsector (education, religion, etc.).

- Giving to a DAF housed in a federated campaign (such as a Jewish trust or federation) is counted in PSB because federated giving is counted in PSB.

To avoid the double-counting issue, we take the net of incoming contributions and outgoing grants when tabulating giving to organizations that house donor-advised funds. This netting out of gifts and grants would also negate any double counting if an individual shifts a DAF from one sponsoring organization to another. If DAF grants were to cross years, from an accounting perspective there might be a “double counting” of the gift in one year, but that over-/understatement of the gift would be exactly offset in another year. In a dynamic steady-state environment, these fluctuations are likely to net out even within any given year. The flowchart below shows how we count things to ensure that individual gifts are only counted once. The chart shows specifically how a gift from one DAF to another is not counted twice.

Other Philanthropic Intermediaries

Besides DAFs at community foundations (as well as at many other charities) and at commercial entities, there are several types of charities that are financial and philanthropic intermediaries; donors make gifts to these charities, and then the charities make grants to their respective communities. These communities could be geographically determined (most United Ways and community foundations), philosophically or religiously coaffiliated (for example, Jewish federations, giving circles, and Catholic charities), or other federated workplace campaigns (for example, the federal government’s workplace and charitable fundraising campaigns).

While we can argue about whether or not these entities increase or decrease philanthropic giving by any one household and/or in the aggregate, it seems likely that they would fail to exist if they did not increase the net social welfare. As with DAFs, concerns have also been posed with respect to double counting these types of gifts. For our estimates for the Giving USA reports, we apply the same principles that we use for DAFs to other pass-through organizations to avoid double counting of gifts. Individual giving to organizations such as United Way chapters or Jewish appeals/federations is counted in estimates of giving by individuals. Giving or grantmaking from these entities is not counted, in order to avoid double counting.

Conclusions and Observations

In sum: There have been questions raised about whether gifts and grants by DAFs and other philanthropic intermediaries such as United Ways and Jewish federations are double counted. While this double counting may occur transactionally on an organization-to-organization basis (as when they are recorded as gifts or grants from one charity to another), the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy’s research scrubs the data in ways that eliminates this double counting.

There have also been questions about whether foundations (and—especially—DAFs) serve as instruments for donors to “park their money” indefinitely while still realizing a tax-deductible gift today. While one might haggle over whether or not the payout rates could or should be higher for foundations—or be created for DAFs—we need to remain cognizant that these gifts all represent permanent commitments to philanthropy. While some of the gifts might have gone directly to charities without these financial intermediaries for philanthropic giving, some would never have been made as philanthropic gifts absent such giving vehicles. The factors may vary—from the timing of liquidity events to the desire to provide opportunities for subsequent generations to learn to become philanthropists or even the desire to not leave too much money for one’s heirs. Despite the differences in motivation, society is enhanced by the range of options that allow prospective donors to use these tools both for their personal benefits with respect to timing and platforms and for society’s benefits from these permanent commitments to philanthropy.

The debate on the spend-down versus perpetuity on the expected tenure of foundations (and endowed DAFs) has garnered lots of attention and debates in the popular as well as academic presses. Philanthropic giving decisions are private decisions about the best ways to address the challenges society faces now and in the future (including intergenerational equity concerns, which include environmental and social justice issues). There is not one right, cookie-cutter answer. Rather, society and philanthropy both benefit by allowing donors to decide which giving vehicles best enable them to achieve their philanthropic mission for the causes—and over the time periods—they elect to support.

Other Questions about Double Counting: Daisy Chaining, Giving to Individuals (Pharma Gifts of In-Kind Products), and the Like

Daisy Chaining. Questions about daisy chaining refer to the possibility of double counting grants or gifts from one charity to another. This term was coined with respect to aid organizations regifting in-kind gifts to one another. The concern was whether this was being captured as multiple gifts in the research totals and also in the financial tallies of individual nonprofits (this may be used by nonprofits to inflate their revenue bases, making themselves look bigger than they are and throwing off their program spending ratios). Giving USA avoids the first by not counting gifts from one charity to another.

Giving to Individuals. A new “uses” of giving category, giving to individuals, was added to Giving USA estimates in the last decade or so. The category was added to capture the amount of gifts of in-kind products made directly to individuals by pharmaceutical firms (frequently called “patient assistance programs”), which comprise the majority of this category. This money does not go through a pass-through entity but rather is a tabulation of the amount that institutions are giving directly to individual Americans. In some ways, this is an oddity for Giving USA, as these are not gifts to or from a charity. The recipients may be better off getting these gifts in-kind directly from the source—both from a health perspective and an after-tax income perspective—rather than getting the same value in cash.

What’s Left for Charitable Programs after Fundraising Costs?

This is clearly a valid concern, but this topic is more of a thesis in and of itself and cannot be treated adequately as a brief sidebar. There is a wide range in the return on investment (ROI) from various fundraising tactics and strategies. The introductory methods (special events, telemarketing, direct mail, etc.) are available to all charities and may be the only real options for newer and smaller nonprofits, but they tend to have the lowest ROI.20 Major gift fundraising and planned gift efforts may only succeed once the charity has demonstrated that it is credible and likely to succeed.

Within each tactic, there are many additional permutations and combinations for charities to decide on:

- hire own staff (but costs are up-front and certain and benefits are delayed and uncertain);

- hire outside fundraising advisors (still incur the staff costs with certainty as well as the consulting costs, and the benefits are still delayed and uncertain, but presumably better with greater expertise being applied than from in-house staff only); or

- outsource fundraising completely (but then very few of the dollars actually go to the charity—and often the third-party telemarketers keep the lists of donors, so it becomes difficult for the charity to break this chain of dependence).

We also know that when charities and their staffs feel significant pressure to report low fundraising costs to donors, funders, regulators, and the media, some charities will simply reallocate their fundraising and/or management and general costs to program costs.21 This drives down their reported fundraising cost ratios but creates even greater pressure on other charities to report low fundraising costs. While most nonprofits make great efforts to accurately track and report their true fundraising and overhead costs, those that understate them create a death spiral toward zero (only because these costs cannot be negative). Such moves create false expectations for donors and funders, and mislead the public.

Innovations in Giving Platforms: Crowdfunding, MoveOn.org, and the Like

Normally not counted as part of Giving USA measurements or other measurements of formal giving—i.e., giving to a legal charity, 501(c)(3)—crowdfunding is considered to be “informal philanthropy”—i.e., giving from one person directly to another. In some ways, crowdfunding may be a substitute for formal giving (medical relief, disaster relief, etc.). In other ways, it is a supplement to formal giving (such as helping somebody with something for which they would be unlikely to obtain help from a formal giving mechanism—such as money for me to go to Spain to write my poem, or providing a scholarship to a child who lost her parents in a tragic situation). Crowdfunding and the social media supporting it have made these types of informal giving much more visible.

It is not clear yet whether these crowdfunding gifts are supplements to or substitutes for traditional gifts to legal charities. While this may be unknowable in some ways (it is hard to prove what might have happened if these options did not exist), even just tracking the flows and the differences in the rates of flows is difficult. This is because crowdfunding and other forms of informal giving have not been tracked historically, and the few high-quality studies of formal giving do not ask about crowdfunding, making it effectively impossible to gauge whether crowdfunding is net new giving (i.e., on top of traditional giving), or if it is largely displacing giving to formal charities. Given that crowdfunding and formal giving are both growing, it seems likely that they are largely supplemental rather than substitutes—but that is based on inferences rather than concrete evidence.

Online platforms such as MoveOn.org have made fundraising associated with a cause on which the donor is also taking action easier; but these are considered to be political, and political donations are not considered philanthropic gifts, so they are not tracked or counted in studies of charitable giving. Whether political giving is “crowding out” philanthropic giving is difficult to measure and is the subject of many academic papers. The simple answer is that political giving does not appear to be crowding out philanthropic giving—at least at the macro or aggregated levels, as is demonstrated by the fact that both political giving and philanthropic giving set new records in the last presidential election cycle. Whether these new types of giving platforms are “crowding out” gifts to traditional charities is impossible to measure with any level of precision, but so far there is no evidence to support that suggestion.

Clearly, some of the issues in this article cannot be tested precisely, given the lack of data and/or the lack of comparability over time. Others cannot be tested given the lack of controls and “what ifs.” That said, measuring the payout rates of DAFs, the impact of spend-downs and permanent foundations, the costs of fundraising, and so forth will be helpful to donors, fundraisers, and nonprofit leaders. It would also be ideal to compare philanthropic giving and political giving at the household level to measure whether or not political giving “crowds out” philanthropic giving in some households—and, if so, what we can learn from those circumstances.

The views in this essay are strictly the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of Indiana University, the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, or Giving USA or any of the other research projects the school undertakes. The author thanks Ji Ma for the flowchart graphics, Jon Bergdoll and Jon Durnford for fact-checking the methodology sections, and Anna Pruitt, Adriene Davis, and Lisa Rooney for editorial suggestions.

Notes

- 2016 Donor-Advised Fund Report (Jenkintown, PA: National Philanthropic Trust, 2016), 4.

- Marc Gunther, “The Charity That Big Tech Built,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Fall 2017.

- This table was created by combining two tables from the 2016 Donor-Advised Fund Report. For the original tables, see “Comparison of Giving Vehicles,” section 5, tables 2 and 3.

- Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (New York: Harper and Row, 1942).

- Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, Giving USA 2017: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2016 (Chicago: Giving USA Foundation, 2017), 358.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 359.

- Ibid., 356–7.

- Ibid., 357.

- Ibid., 71.

- Marc Gunther, for example, uses this term repeatedly. See Gunther, “The Charity that Big Tech Built.”

- 2016 Donor-Advised Fund Report, 5.

- See Giving USA 2017, “Special Section on DAFs,” 69–88.

- 2016 Donor-Advised Fund Report, 6.

- Akash Deep and Peter Frumkin, “The Foundation Payout Puzzle,” in Taking Philanthropy Seriously: Beyond Noble Intentions to Responsible Giving, ed. William Damon and Susan Verducci (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2006): 189–204; Renee A. Irvin, “Endowments: Stable Largesse or Distortion of the Polity?” Public Administration Review 67, no. 3 (May/June 2007): 445–57; and Stefan Toepler, “Ending Payout as We Know It: A Conceptual and Comparative Perspective on the Payout Requirement for Foundations,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 33, no. 4 (2004): 729–38.

- Ellie Buteau, Naomi Orensten, and Charis Loh, The Future of Foundation Philanthropy: The CEO Perspective (Cambridge, MA: Center for Effective Philanthropy, December 2016).

- Amy Markham and Susan Wolf Ditkoff, Six Pathways to Enduring Results: Lessons from Spend-Down Foundations (Boston: The Bridgespan Group, October 2013).

- Patrick M. Rooney, Richard C. Sansing, and Jon Bergdoll, “Public Policies and Private Foundations: Payout Rates and the (Dreaded) Excise Tax,” in The Handbook of Research on Nonprofit Economics and Management, 2nd ed., ed. Dennis R. Young and Bruce A. Seaman (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, forthcoming).

- Alan Cantor, “Donor-Advised-Fund Payout Numbers Don’t Add Up,” The Chronicle of Philanthropy, July 13, 2017.

- See Patrick Rooney, Mark Hager, and Thomas H. Pollak, “Fundraising Tactics and Efficiency: Results from a National Survey,” working paper, Urban Institute and Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University, 2003.

- Kennard Wing et al., “Functional Expense Reporting for Nonprofits: The Profession’s Next Scandal?,” CPA Journal (August 2006), 3–7.

Patrick M. Rooney is executive associate dean for academic programs and professor of economics and philanthropic studies at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy.