Editors’ note: Good leadership requires moments of reflection in which we think about the dynamics at play in the systems we seek to change. This new column by Mark Light, who has penned NPQ’s “Dr. Conflict” column for years, addresses the lens shifting that we must do in those moments in order to be effective over time. This article is from NPQ’s winter 2017 edition, “Advancing Critical Conversations: How to Get There from Here.”

My wife once gave me a marvelous gift. It was a sealed glass ecosphere about ten inches high and filled with water, tiny brine shrimp, and algae. Very elegant—a real conversation piece. The ecosphere is also the perfect pet; all you have to do is watch the dozen or so shrimp swim around. You never have to feed them, because the sphere is a sealed, self-contained world: The algae produce oxygen; the shrimp consume the oxygen and the algae; bacteria clean up after the shrimp, breaking the waste down into nutrients; algae feed off the nutrients and light energy in order to replenish; and so on. Just add some low light, and you’re good to go.

About the same time that I received my ecosphere, I was serving as the president of Dayton, Ohio’s Arts Center Foundation, where we were building the $130 million Schuster Performing Arts Center. I spent a lot of time in meetings with arts leaders whose agencies would eventually perform in the new center. These folks were thrilled with the project but worried about whether the center was going to bring in big-name national and international artists who would compete with the local arts groups.

Our agency’s philosophy at the time was “do no harm.” We subsidized the rents and provided ticketing services and other benefits. To reassure the local groups about the center’s intentions, I would bring out my little glass ecosphere to make my point that we were all in it together. “Our local arts groups,” I would say, “are a delicate ecosystem that needs to be carefully nurtured.” So, we would forgo opportunities like presenting the Cleveland Orchestra.

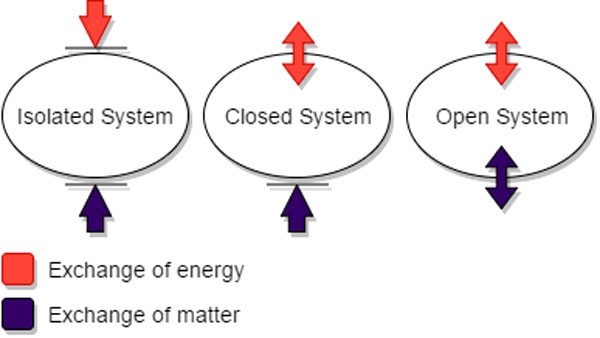

One day, a few years after opening the new center, I was shocked to notice that all the shrimp were dead. I called the manufacturer of my ecosystem and found out that this was completely natural—the inevitable result of a closed system, where there are no matter exchanges with the outside. I also discovered that these ecospheres are not so good for the social life of the shrimp, and their popularity are threatening the shrimp population in Hawaii. And, horrifyingly, the shrimp are in fact dying a slow death over the course of their two-or-so years of existence in the ecosphere, due to semi-starvation, lack of proper oxygen, and micro amounts of toxic waste. This species of shrimp, it turns out, can live up to twenty years in a more favorable environment.

Bottom line is that closed systems like my ecosphere will eventually run out of energy and die. In its quest for preservation and protection of its boundaries, the closed system exhausts all of its resources and collapses. Open systems, on the other hand, get energy from their interactions with the outside world. Closed and open systems are very much like monopolies and open markets. In monopoly environments, things can go to hell in a handbasket because there’s no incentive to make the improvements and innovations that come naturally with open systems. In open systems, competition keeps everyone on their toes; it’s a good thing, because it keeps the system fresh and excited, and always responsive.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

What had I done by encouraging a closed system?! When it comes to the arts, we should absolutely treasure our local talents. Heaven only knows what we’d do without them. But a dose of Chicago Shakespeare Theater every once in a while is hardly a threat. In fact, it may be the very lifeblood that we need to keep from becoming anemic.

Fast-forward to the present: The Schuster Center is still a centerpiece of downtown; Broadway shows continue to come to town, but generally play fewer performances; there was a merger of the Dayton Opera, Dayton Ballet, and Dayton Philharmonic back in 2012; and a couple of agencies exited the stage, including an annual folk festival. Overall, and thanks in part to a very generous bequest, the arts in Dayton and the Schuster Center are still moving along, give or take. According to IRS 990s, Culture Works—the united arts fund in Dayton—showed revenues of about $1.7 million in its 2003 filing (when the Schuster Center opened) and $852 thousand in 2016. The Dayton Art Institute had $4.9 million in 2003 and $5.8 million in 2015; and the Victoria Theatre Association reported $13.3 million in 2003 and $13.8 million in 2015.

If you were on the edge of your seat waiting for a dramatic end to the story, be prepared for disappointment. It takes years for the results of any system to fully manifest. Closed systems don’t collapse apocalyptically, and open systems don’t make it to the stars overnight. Amazon’s rise to prominence took eighteen years.

What’s a leader to do? Stay open: open to new ideas, open to learning from the best, open to open borders. Do not close yourself off from ideas better than your own. Do not be afraid to have others (clients, audiences, customers, employees, board members, etc.) join you in this journey to being the best that you can be.

In the 1996 documentary Triumph of the Nerds, Steve Jobs summed up Apple’s success with the Macintosh computer: “It comes down to trying to expose yourself to the best things that humans have done and then try to bring those things into what you’re doing.” You can’t do this in a closed system. Based upon the ecosphere, I will always bet on the open system. But don’t take my word for it: talk to the shrimp. Oh, wait—they’re dead.