July 20, 2018; Indian Country Today

Last week, the National Indian Education Association (NIEA), a national nonprofit dedicated to strengthening Native education, released a handbook entitled “Sovereignty in Education: Creating Culturally-Based Charter Schools in Native Communities.” For nonprofit organizations working within Native communities and those considering starting charter schools, the handbook provides several key insights to understanding the unique landscape within Native communities in a way that respects their cultural heritage as well as their sovereignty.

The handbook offers a Native-centric framework for charter schools, provides context and solid strategy for starting one, and highlights examples NIEA considers strong. Interested readers will also find public policy reflections, ways to approach student assessment that mirror Native educational philosophy, school governance considerations, and the importance of integrating Native language into the classroom. The latter part looks at operation components, including administration, funding, admissions, and communications. The final section explores sustaining a charter school and discusses the importance of strategic planning, infrastructure, educational advancement, and other concerns.

The background and history of Native education cannot be ignored, as the need to reexamine and change policies and practices dates back to the founding of boarding schools as early the mid-1750s. As the 2014 Native Youth Report, published by the Executive Office of the President, illustrates:

The hallmarks of colonial experiments in Indian education were religious indoctrination, cultural intolerance, and the wholesale removal of Native children from their languages, religions, cultures, families, and communities. The overlapping goals of this “education” and “civilization” operated as euphemisms and justifications for taking culturally and physically injurious actions against Native children and their peoples. As a tool of colonization, education served the dual purposes of imposing European and Euro-American cultures and justifying seizure of Indian land.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The long journey toward respect for Native nations is complicated and too long to detail in this newswire, but it is worth noting that a significant shift in Native-controlled education took place just over 50 years ago, with the Navajo Nation in Arizona opening the first Native-controlled school—the Rough Rock Demonstration School— in 1966, as well as the founding of several tribal colleges in the late 1970s spurred by the passing of the Tribally Controlled Community College Assistance Act in 1978. A few years later, a national gathering of American Indian scholars occurred at Princeton, and one of the major themes that emerged was the need to create effective tools, practices, and discussions regarding Native education. This gathering catalyzed the founding of NIEA in 1970. (For a general overview of the history of Native education in the United States, see Education Week’s timeline, “A History of American Indian Education,” by Jon Reyhner from 2013.)

While there have been gains in Native education, there are also major gaps. Nationally, over 600,000 Native students attend public and Bureau of Indian Education (BIE)–operated schools. According to a report by the Education Trust in 2013 called “The State of Education for Native Students,” there are significant achievement concerns for Native students. The report highlights substantially lower achievement rates for American Indian students in elementary and middle school, and notes that 69 percent of Native students graduate from high school, compared to 83 percent of white students.

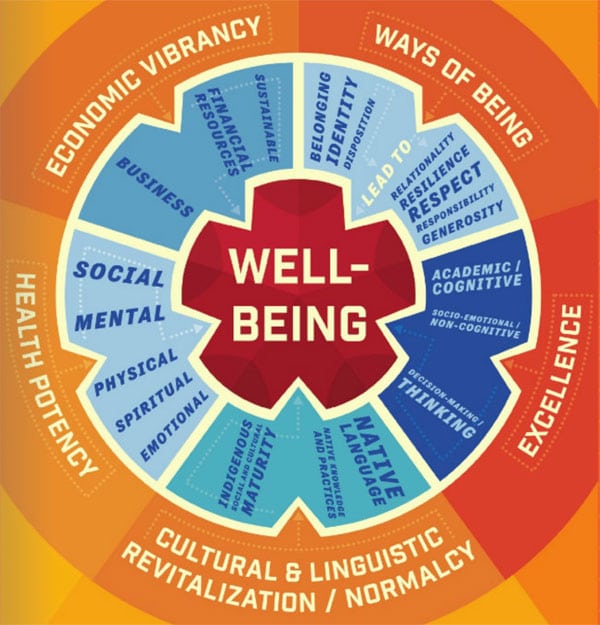

With this historical backdrop, charter schools offer an opportunity, as they can provide culturally appropriate education and have shown promising results. As the NIEA handbook states, “Fundamentally, charters that are grounded in Native ways of knowing, believing, and operating provide an education avenue that many Native people have sought for decades.” And successful Native charter schools are moving the needle. For example, the Native American Community Academy (NACA) in New Mexico, which operates six schools that reflect and incorporate Native culture, tradition, and language into their curriculum, has had a graduation rate of 90 percent.

Yet, despite the promise of charter schools for improving outcomes in American Indian populations, not everybody is embracing them. As NPQ reported in April, the Sovereign Community School in Oklahoma has been stymied in its attempts to establish a school, having been denied twice by the Oklahoma City school board. The school aims to model its program after NACA schools, and the case is now going to the state education board.

Native education advocates should explore the NIEA handbook to discern whether it’s worth trying the charter school approach in their communities. Overall, the handbook is a practical starter kit for those looking at charter schools as a path for increasing Native educational achievement and preserving culture.—Derrick Rhayn