Community economic development approaches have lost their way. Many solutions to social and economic challenges focus on how to expand access to a system from which communities have been intentionally and systematically excluded. These “solutions” may pay lip service to root causes but fail to acknowledge that for certain communities to amass wealth in a capitalist framework requires the harm and exploitation of others along class, race, and gender lines.

As practitioners, to remedy this, it is our job to find our way back, or better yet, forge a new, more powerful path that centers “repair.” Unless we recognize that racialized capitalism’s primary concern is maximizing profits at all costs, we aren’t doing much to sustain equity with, by, and for our people and planet. A growing number of practitioners and organizations, backed by a robust field of study and ancestral practice, instead believe that economic systems can produce everything our communities need and desire without destroying the cultural, social, and economic wellbeing of others.

Rondo Community Land Trust is among this growing movement. Named after the historic and predominantly African American neighborhood in Saint Paul, MN, Rondo CLT is reimagining (or reclaiming) tools and frameworks that establish the needed conditions for a more human and earth-conscious economy. Rather than simply expanding access to an extractive system, our work aims to shift the paradigm of community economic development approaches.

A Neighborhood Split by a Highway

Rather than simply expanding access to an extractive system, our work aims to shift the paradigm of community economic development approaches.

For Rondo CLT, our work and ethos are directly tied to our lived experience. The insular nature of Saint Paul’s historic Rondo neighborhood (albeit forced through racial segregation employing racial covenants and redlining) created the conditions for a deeply interdependent and cooperative economy to flourish.

However, the construction of Interstate 94 (spurred by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956) in the fifties and sixties caused severe disruptions. The immediate impacts were that long-time residents were displaced from their homes and businesses were uprooted from their storefronts.

Generational impacts are far-reaching and reverberate this day across all social determinants of health. It is now evident that Black families were grossly underpaid for the sale of their homes. According to a 2020 study commissioned by the nonprofit ReConnect Rondo and written by the Yorth Group, “The Intergenerational Wealth Gap that was caused by I-94 and poor land use and planning resulted in a loss of at least $157 million by 2018.” The report added that “over 700 homes were lost to I-94. Along the way, the ecosystem for the previously thriving local economy was destroyed with many businesses closing as a result.”

Moreover, according to the 2017 Ramsey County’s Health Equity Data Analysis report, increased air pollution from the highway has contributed to Rondo residents having “one of the lowest lifespans when compared to other areas of Saint Paul.”

Three short miles away, the West Side of Saint Paul, specifically an area referred to as “The Flats,” shares a similar history. Many residents recall and know the West Side as the “little Ellis Island of Saint Paul,” serving as the first neighborhood where many immigrants (Jewish, Mexican, Lebanese, Syrian, and many others) got established when they came to the city.

The Mississippi River frequently flooded the area, particularly in the early 1950s when residents faced a series of devastating floods. Later, these floods were used as pretext to displace families from their homes, and only afterward was a levee built to hold back the waters and allow for industrial development. Today, the West Side Community Organization is a powerful actor documenting stories and advocating for reparative action.

Both stories of historic displacement have had devastating impacts on generations of families, who nevertheless have fought to maintain their identity and culture.

Communities are challenged to be radically imaginative, take risks, and center a spirit of abundance, even as they face chronic underfunding.

And it doesn’t end there. Communities across the nation share eerily similar experiences. Detroit’s Black Bottom and Paradise Valley neighborhoods, the Greenwood District in Tulsa, OK, and Sweet Auburn Avenue in Atlanta, GA, all carry comparable scars.

With this shared history, many organizations in proximity to the communities harmed by injustice, including ourselves, have been picking up the pieces. We’re doing our best to rebuild what was lost and hold water against ongoing cycles of investment and disinvestment. This requires taking on projects at contaminated sites in severe disrepair, which are more frequently than not financially upside-down, meaning the investment needed to redevelop is higher than the building’s value at project completion. So, these projects must attract greater subsidies than competing projects in more affluent neighborhoods.

By contrast, for-profit developers have less difficult projects to fund, more dollars to invest, and powerful social capital to wield. The cycle continues. Community groups get further behind and lose ground.

In short, communities are challenged to be radically imaginative, take risks, and center a spirit of abundance, even as they face chronic underfunding and their leaders (especially people of color and women) are held to impossible standards (by system players, but, if we’re being brutally honest, also by our own peers). Often, community groups are forced to use tools that replicate the very systems they seek to change.

Despite these challenges, time and time again, communities rise to the occasion.

Envisioning a Reparative Economic Development Framework

In the spirit of solidarity, Rondo CLT offers our reparative economic development framework, which reflects our best (and constantly evolving) thinking and practice. Powered by the ingenuity and expertise of our communities, we apply this framework to our unique role as a commercial and residential land trust and real estate developer, but we believe this framework can be applied broadly.

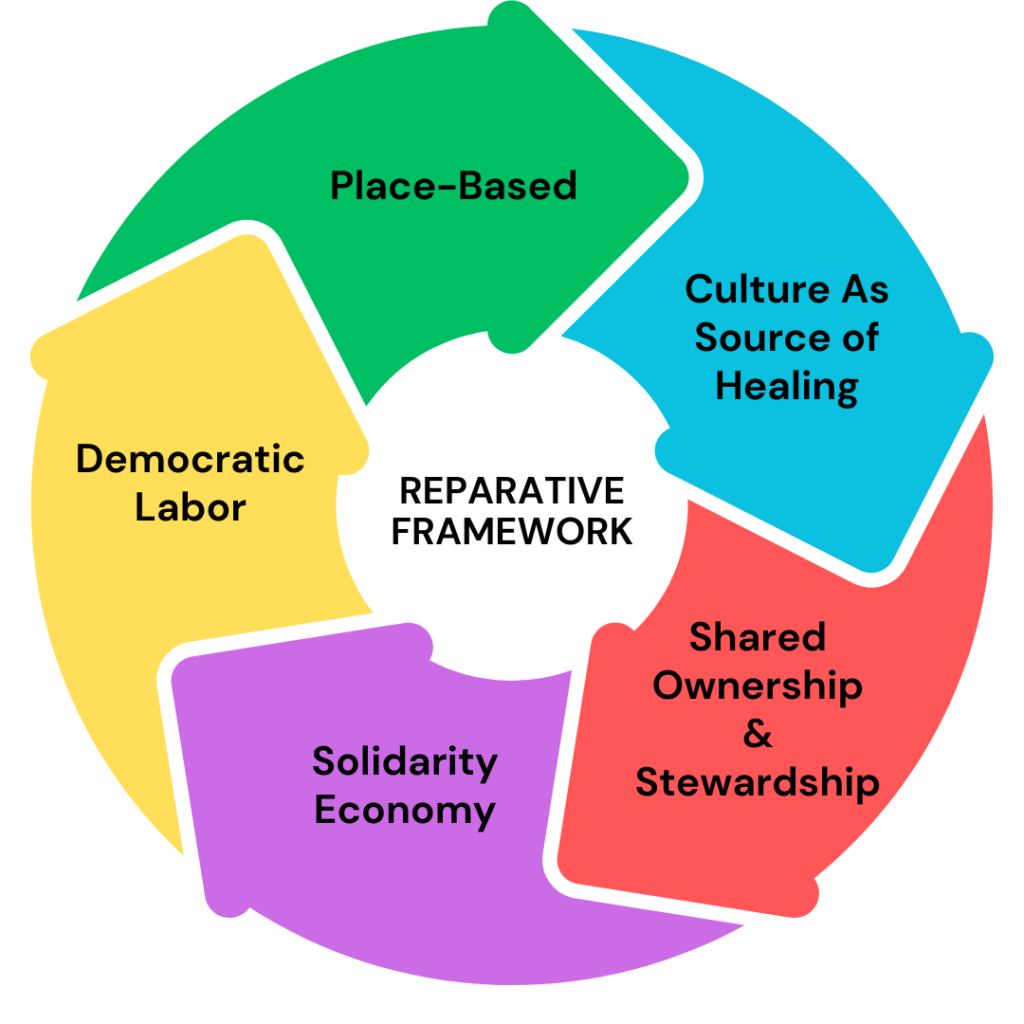

The key dimensions of our approach (and displayed in the graphic below) are as follows:

1. It is place-based: Each place carries a unique history, acting as a sanctuary of memories and a mirror of cultural identity. Reparative strategies will, therefore, be more resonant and surgical if tethered to place with data that starkly document past harms in dollars-and-cents terms.

2. It sees culture as a source of healing: Economic violence doesn’t just have financial impacts; it also tears the social and cultural fabric of communities. Reparative efforts that exclusively tend to the revitalization of wealth do not provide the depth of healing our communities are hungry for. Culture carries ancestral ways of relating to one another, offers solutions, and heals unseen wounds.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

3. It emphasizes shared ownership and stewardship: As is made evident by our lived experience, ownership in the capitalist system doesn’t protect us from wealth stripping and other forms of economic violence. Shared ownership models—land trusts and cooperatives—broaden political and economic power. It gifts us structures that spread risk, share reward, and spur mutual accountability.

4. There is a focus on building a solidarity economy: A solidarity economy centers relational and human values in the production and exchange of goods and services. When we match economy building with place-based strategies, we set the conditions for circular economies.

5. There is a commitment to democratic labor: We believe in people power and that democratic workplaces produce better results for local economies and workers.

Applying the Reparative Framework in Practice

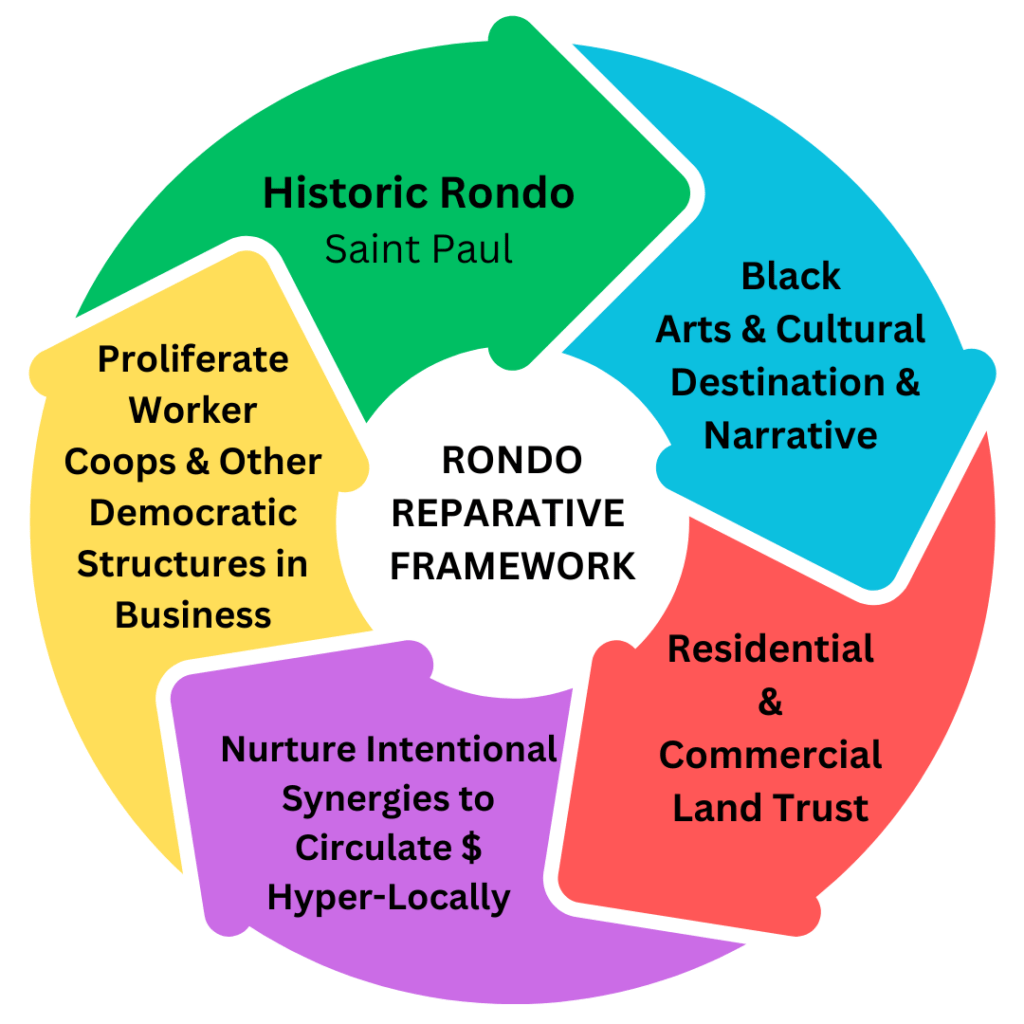

These principles all sound good, but how are they applied in practice? The Rondo reparative framework, pictured below, which seeks to combine a community land trust with promotion of worker ownership and support for Black arts and cultural initiatives, offers our attempt to make the principles outlined above real:

One aspect of this is an initiative that centered on a right to return to Rondo. Formally launched in 2019, this is an explicitly reparative effort bridging home and business ownership opportunities to individuals and descendants displaced by I-94 by offering first right of refusal to any existing or acquired properties within historic Rondo boundaries—a place-based concept.

Guided by the broad goal of bringing back the 700 homes and reseeding the 300 businesses lost, Rondo CLT is pursuing strategic acquisitions within historic Rondo for rehabilitation or new construction. For homeownership, the land trust layers on an affordability investment (up to $150,000), an additional $60,000 for rehabilitation (including energy efficiency retrofits), and “reparative” funds (up to $50,000). The goal is to achieve $224,000 in direct cash assistance per home (this number is achieved by taking $157 million in lost intergenerational wealth divided by 700 homes).

In this manner, Rondo CLT seeks to achieve multiple layers of repair, both individual and community-centered, by ensuring that the home is held in trust through shared ownership—recycling affordability for generations of families.

In the commercial sphere, Rondo CLT operates a small incubator to help advance a solidarity economy. The land trust also purchased a legacy Black business for worker-ownership conversion in accordance with our principle of democratic labor.

This effort to accelerate and deepen the applicability of the reparative framework in Rondo relies on a web of values-aligned partnerships. Specifically, the Saint Paul Shared Ownership Collaborative—in which Rondo CLT is one of four members, alongside the neighborhood-based West Side Community Organization, the regionwide Metropolitan Consortium of Community Developers, and the social service group Model Cities Saint Paul—advances shared-ownership models in both housing and business, while also building community power.

The local and national landscape is ripe for this reparative framework to take root and spread. Under Mayor Melvin Carter—a son of Rondo and the city’s first Black mayor—several recent initiatives provide tools and resources to community-based efforts. For example, the Inheritance Fund provides down-payment assistance and home rehabilitation dollars to “direct descendants of a property owner whose property was acquired by Minnesota State Department of Transportation for the Interstate 94 highway project between Lexington Avenue and Rice Street.”

We see shifts at the state level, too. In 2023, the Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED) allocated $3 million for a “Community Wealth Building” loan program specifically designed to support worker cooperatives, commercial land trusts, and other land-based cooperative strategies.

New Waves, Old Wounds

In 2006, years after the I-94 highway cut through the bustling heart of Rondo, a light rail line was proposed to connect downtown Minneapolis to downtown Saint Paul, which ultimately became the Green Line. The initial proposal left many frustrated, but people were not surprised when plans showed that the upper edge of historic Rondo and surrounding majority BIPOC communities would not receive station stops.

Using a reparative framework can help guide collective work and…center communities as owners.

To add insult to injury, those who lived in the neighborhood throughout the period of the highway’s construction and managed to literally hold their ground, now elders, were flooded with the deep-seated fear that they would not be able to survive another wave of infrastructure “improvement” and might have their homes once again seized from them.

Fortunately, local organizations—such as the Saint Paul NAACP and Aurora St. Anthony Neighborhood Development Corporation (then led by a daughter of Rondo, Nieeta Presley, who also founded the Rondo Roundtable)—mobilized. These activists and elders ultimately succeeded in getting the transit authority to agree to include stops at Western, Victoria, and Hamline Avenue in historic Rondo. Over time, these have proven to be some of the busiest stops along the line.

Will New Federal Investments Benefit or Harm Us?

In 2024, our efforts persist to repair and build anew. Arguably, one of the greatest leverage opportunities in front of us are the unprecedented infrastructure dollars flowing from the federal government.

These are becoming available at the same time as the state’s Department of Transportation is holding hearings on its “Rethinking I-94” initiative, which is “a long-term effort to engage with those who live, work, and play along the corridor between Minneapolis and St. Paul.” Expanding the highway, capping the highway with a land bridge, or replacing the highway with a multimodal boulevard concept are among the ideas emerging from community stakeholders.

Naturally, the process of “rethinking” I-94 has kicked up animated debate regarding both what our communities need for the future and what our communities deserve as restoration for the past. Moreover, as larger infrastructure projects sit on the horizon—construction is currently not slated to begin until 2028—we know residents need to be protected from displacement now.

As communities across the nation scramble to capture these funds, it behooves community developers to demand better of ourselves and the field. Using a reparative framework can help guide collective work and elevate questions about who will not only benefit as consumers from infrastructure projects but center communities as owners—a particularly critical concern for renewable energy generation and distribution.

It’s too early to tell how it will all shake out. But we know this to be true: slapping new technology on something, whether it’s to increase urban density, decarbonize, or build more climate resilient communities, won’t serve as a conduit for justice unless our communities are made whole.