Editors’ note: This article, first published in print during Jan/Feb 2014, has been republished for Nonprofit Quarterly with minor updates.

This exercise is adapted from a new book, Train Your Board (and Everyone Else) to Raise Money: A Cookbook of Easy-to-Use Fundraising Exercises, published by Emerson and Church, emersonandchurch.com. Used with permission. The 50-plus exercises in the book were contributed by the authors and nearly a dozen other trainers and consultants.

Far too often, we treat our donors like ATMs: every contact is about extracting money. If you are planning a fundraising campaign—especially a major donor effort—it is important to think strategically about keeping donors informed and involved. By focusing on assignments and time commitments, this activity helps create structure and accountability.

WHY DO THIS EXERCISE?

To create a specific task-and-time list for strengthening outreach to donors.

USE THIS EXERCISE WHEN

You want to reality-test the number of donor relationships you can actively manage.

TIME REQUIRED

30-45 minutes

AUDIENCE

Anyone involved with your fundraising campaign: some combination of board, staff, and volunteers —especially those who are preparing to meet with donors.

SETTING

Anywhere you gather to work on your campaign plan and train your participants.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

MATERIALS

Flip chart paper and markers.

FACILITATING THE EXERCISE

- Brainstorm with your colleagues specific tasks your organization might use to engage donors more deeply after they give; for example, “Invite to lunch,” “Email updates,” and “Volunteer opportunities.”

- Discuss with the group how much time each task will take and then assign an amount of time per task, per donor, per year. Depending on the number of people present, you can discuss this with the full group or break into smaller groups.

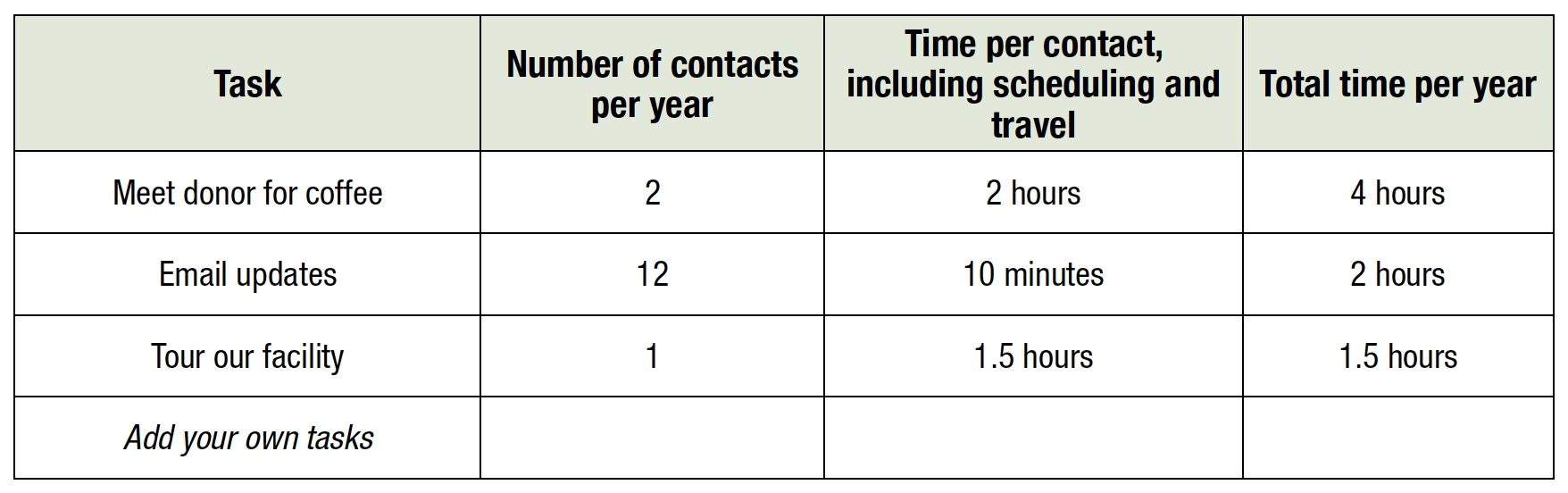

For example, your list might include the task

“Meet donor for coffee.” Assuming two meetings per year for the average major donor and two hours to schedule, travel, conduct each donor meeting and make notes afterward, the time allocated for this task would be four hours per year per donor. See the sample task list below.

- Once you have determined the amount of time for each task, write the time on the flip chart. Add up the numbers. You have a rough estimate of the number of hours per year needed to involve and engage an average donor.

Since every donor is different and requires varying levels of engagement, the total hours will be only a rough estimate—but a rough estimate beats a wild guess. The process of thinking through this question will help your volunteers figure out how many donors they can realistically engage during the year.

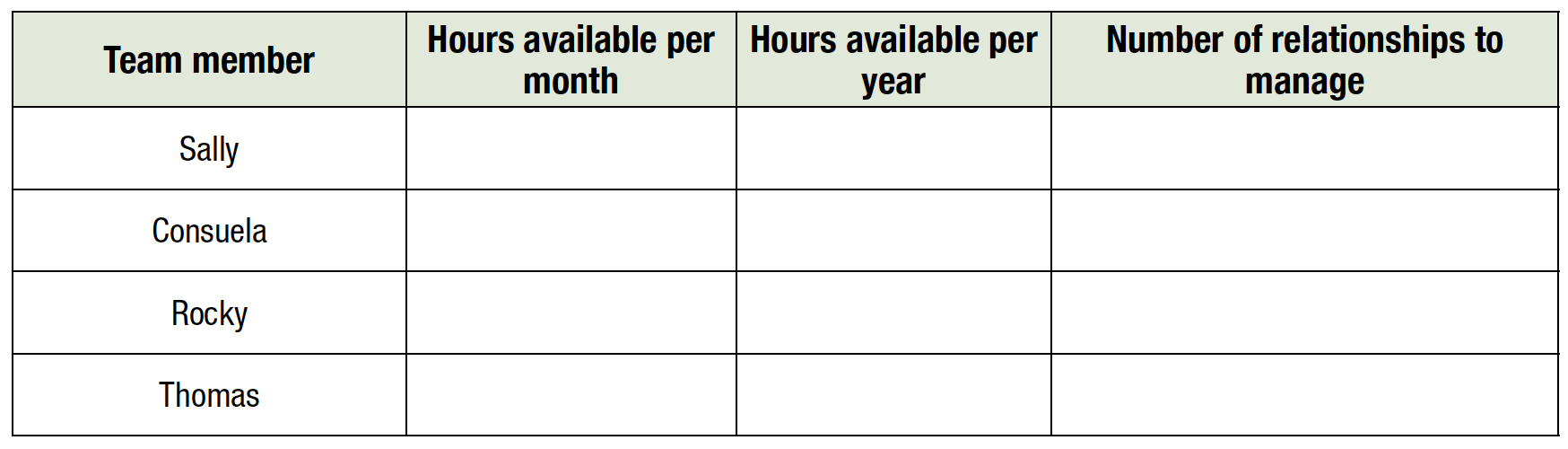

- Write the names of your fundraising team members on another flip chart page. Ask them, “How many hours per month do you have available to spend on donor relationships?”—then multiply by twelve. Write the annual number of hours after each name.

- From here, it’s an easy step to answer the question “How many relationships can you manage?” Divide the number after each team member by the total number of hours per year it takes to engage a donor. For example, if your average donor requires 12 hours annually, and Sally has 36 hours per year available, Sally should be assigned no more than three relationships.

- To debrief this exercise, ask the following questions:

- Looking at the chart, does the number of relationships assigned to you seem realistic?

- With the understanding that each donor is different, how do we customize this list? For example, we know Mildred doesn’t use email—how will we reach her instead?

- What systems do we need to have in place to hold each other accountable?

The best time to conduct this exercise is before you finalize your campaign goal and gift chart. Too many organizations solicit donations without having a plan to keep their donors involved or knowing how much time it will take. When these relationships are neglected, supporters start to feel ignored, which is a self-defeating way to run a fundraising program. This exercise gives you the tools to design better strategies.

TRAINING TIPS

- You don’t have to be an expert. Sure, it’s easier to train people to raise money if you know something about fundraising, but these exercises are designed to work with trainers (and audiences) of any skill level. When in doubt, remember the old trainer trick: if someone asks a question you can’t answer or brings up a topic you can’t address, pass it back to the group. “Martha, that’s an excellent question. Who has a good response?” If you’re a novice trainer, it’s fine to acknowledge that: “This is my first time leading this exercise, so I’ll need everyone to help me out, OK?”

- Honor your need (or not) for preparation. Some people prepare rigorously before trying something new; others jump in. We have done our best to design these exercises for people who land anywhere along the “preparation spectrum.” If you need to thoroughly prepare in advance, please do. And if you’re comfortable opening the book, reading an exercise, and facilitating it real time, go for it.

- People remember what they do, not what you say. This is the heart of adult learning theory, which is why this book is a series of activities, role plays, and games, not lectures or PowerPoint slides. As noted earlier, you don’t have to be a fundraising expert – you just have to facilitate the group.

- Pay attention to logistics. The success or failure of a training event depends, in large measure, on people’s physical comfort.

- If possible, position the chairs so people can talk to each other – around a table, for example – rather than classroom style or in a large U with people far apart. For many of these exercises, an informal circle of chairs will work well.

- Choose a room with good light, preferably natural light.

- Set the thermostat to a comfortable temperature. If you’re concerned, poll the group – “Is anyone else cold?” – and adjust accordingly.

- Create good sight lines so people can see what you’re writing on the flip chart.

- Avoid glare. Never have the audience facing large windows during the daytime. You (and your easel) will be backlit and difficult to see.

- Use big markers that don’t smell. Some markers are pretty toxic, and your colleagues may have chemical sensitivities.

- Write large letters; large enough so everyone can see clearly. Not sure how big is big enough? Write something, then sit in the farthest chair. Can you read it easily?

- Speak up. Project your voice. Make it carry. Learn to speak from the core of your body, rather than relying entirely on your throat. Ask everyone else to speak up, too. If the room is large and acoustics poor, you may need to repeat questions (loudly) so everyone can hear them.

- Keep things moving: the pace and the people. If you’re a new trainer, you may feel the desire to answer every question and pursue every tangent. We’ve designed these activities to make it easy to stay on task, but unexpected things will happen and it’s your job to address people’s concerns while keeping the group on track. You can always say, “Let’s complete the exercise and then discuss that question when we debrief it together at the end.” If you want to add energy, give people the chance to move. For example, if the exercise calls for work in pairs, encourage everyone to stand up, move around, find a partner, and spread out around the room.

- Be supportive. Reinforce your colleagues by saying things like, “What a great question,” and “That’s a really thoughtful response.” Don’t be dismissive or make people feel like they’re asking dumb questions.

- Listen to the group and trust where they want to go. In some ways, this is a contradiction (see item 4 above), but the best facilitators can sense when it’s time to follow the group away from the agenda and into the work they really need to do. On this topic, it’s best to trust your instincts. If it feels fruitful, go there; if not, stick to the agenda.

- Gimmicks are good. After years of shouting, “Can I get your attention?” Andy finally bought a bell and a train whistle—and they come in handy. Another trick is to make the exercises competitive (some are designed this way) and give out prizes: “The small group that brain-storms the most items in the next three minutes will win a fabulous prize.” This always increases the energy level in the room.

- Debrief everything. Nearly every activity, game, and contest in this book includes a debriefing: a chance to sit together when it’s over and ask, “What did we just learn? How do we apply it?” Sharing these lessons with each other is an important part of integrating knowledge and figuring out how to use it. We encourage you to trust the lessons that emerge during these debriefings, even if they are not the ones you expected at the start of the exercise.

- Share the wealth, share the power. Once you’ve facilitated a few sessions, encourage your colleagues to take turns in front of the room, too.