The common headline in the nonprofit press has been simple: Giving declined in 2022 for only the fourth time in 40 years. (For further details, see this recent NPQ article).

Will 2022’s one-year decline become a longer-term trend? The short answer is: “Unlikely.” After all, if giving has increased 36 of the past 40 years, it will probably rise again.

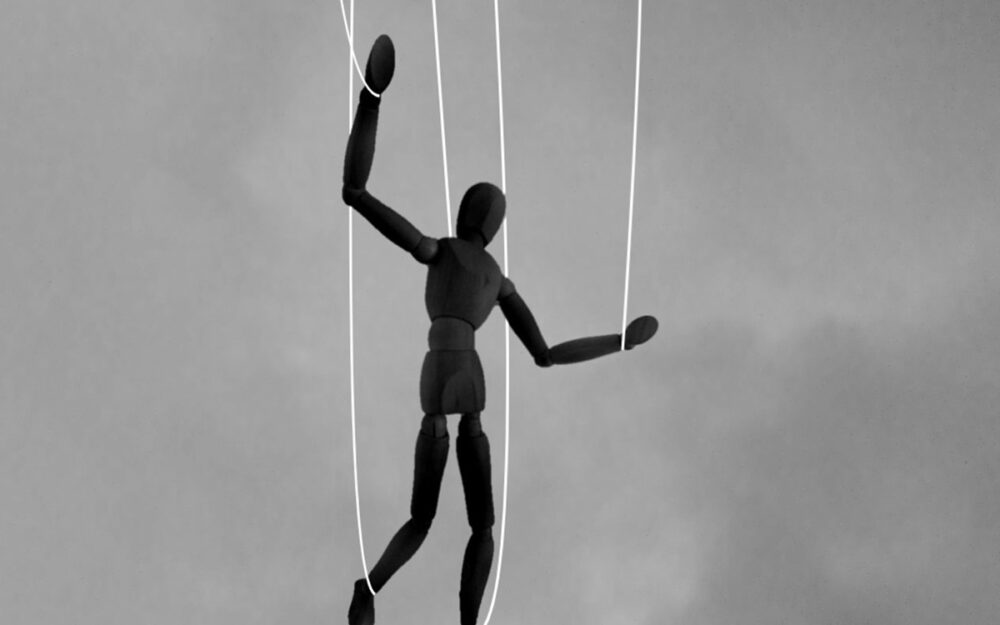

In the age of the megadonor, individual giving is not what it used to be.

But a panel at The Giving Institute’s Summer Symposium made clear that other trends are more concerning. Lauren Steiner, a member of the Giving USA board, moderated the discussion. The panel consisted of three Giving USA leaders: Josh Birkholz, chair of the Giving USA Foundation and CEO of BWF, a fundraising consulting firm; Carrie Dahlquist, co-chair of the Giving USA Advisory Council on Methodology and senior counsel at Campbell & Company; and Anna Pruitt, managing editor of Giving USA and associate director of research at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy.

One key takeaway message: the rise of the über-wealthy in US philanthropy continues. In the age of the megadonor, individual giving is not what it used to be.

Who Gives?

The panelists began by assuaging concern over the one-year decline. For her part, Pruitt noted, “It is really important to put the decline in perspective,” adding that what was really going on was, after a pandemic giving boost, a “return to pre-2020 levels.” Dahlquist concurred and added that “we are still in an upward trajectory in general.”

A bigger concern is the continuing shift in who is giving. Simply put: more and more donations are coming from fewer and fewer people. This, of course, is not a new issue. NPQ covered this now two-decades-long trend at length in 2019. But the trend shows no sign of abating, and the Giving USA panelists were very concerned. “This is what keeps me awake at night,” Birkholz said. Beyond the democratic implications—the more giving becomes concentrated among the wealthy, the more control the wealthy will exercise over where philanthropic dollars go—nonprofit reliance on wealthy donors has other, perhaps less obvious implications. One of these is not so much to expect a decline in giving but rather to expect an increase in the volatility of giving.

As Pruitt explained, “Because there are fewer people giving, it is going to be wealthy people” who are increasingly those who give. Pruitt added that, given that this is the case and given that more than half of individually owned shares are owned by the top one percent, “We might expect trends for giving to resemble more closely [the performance of] the S&P 500,” the stock market index of the nation’s 500 largest stock corporations. In other words, more and more we can expect giving to follow the volatility of the stock market—rising more in years when stock values rise, and falling more in years when stock values decline.

Nonprofit reliance on wealthy donors has other, perhaps less obvious implications. One of these is…to expect an increase in the volatility of giving.

Growing Reliance on Donor-Advised Funds

Another way that the wealthy give differently than those who are less wealthy is the growing tendency of wealthy donors to donate first to donor-advised funds (more commonly referred to as DAFs), rather than donating directly to nonprofits of their choice. The way DAFs work, technically speaking the money ceases to belong to the donor once they donate to the fund; however, practically speaking the donor can “advise” the fund on which nonprofits they should open their checkbooks for, with the donor’s “advice” being honored by the fund administrator in nearly all cases.

For the first time, this year’s Giving USA report included a chapter on DAFs. To date, the group has accumulated two years’ worth of data. Obviously, in future years they will have more data, allowing for more long-term analysis. Pruitt noted that analyzing DAF distributions is critical to getting a full picture of giving: if DAFs were counted as a category, in 2021 they would be responsible for 8.9 percent of all giving—a number, she noted, that is greater than all corporate giving combined.

There is also a lag in acquiring data on where DAF dollars go. Pruitt said that this year’s Giving USA report could only compare DAF giving for 2019 and 2020. We will not know what DAF contributions to nonprofits looked like in 2022 for a while yet.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

What the 2020 data does permit, however, is to “really isolate what happened during the [first year of the] pandemic.” In particular, in 2020 there was an extraordinary 78-percent increase in grants given through DAFs to nonprofits. This means that many donors with DAFs did draw down on funds in their accounts that year, with DAF donations thus serving as a kind of “rainy day” fund, as advocates had promised.

As large donors become more important, nonprofits…adjust their fundraising practices to attract those donors.

A related issue concerns who gets the money that is disbursed from DAFs. Historically, Pruitt noted that education and religion were the most common categories, with education receiving by far the largest share of DAF dollars. Earlier research Pruitt did with her colleague Jon Bergdoll found that from 2014 through 2018, 28 percent of DAF dollars went to education, with religion coming in second at 14 percent. In 2020, however, while education remained in first place, there was a major increase in DAF grants being directed to “public sector benefit” organizations, a category that includes civil rights, voting rights, and community development finance. In 2020, 16 percent of all DAF grants were made in this category, and voting-rights groups and others, such as the American Civil Liberties Union, benefitted from this shift.

How the Shift in Who Donates Affects Fundraising Itself

Birkholz noted that, beyond DAFs, in individual giving education traditionally has been one of the top three donor categories, but for younger donors it has dropped to fifth or even sixth position. Part of the reason for this decline in interest seems obvious—if you’re a younger person who is still making student loan payments to cover inflated tuition costs, why would you give to a university?

But Birkholz observed that there is another factor at play: namely, as large donors become more important, nonprofits, including university development departments, adjust their fundraising practices to attract those donors. As Birkholz put it, “We have built a model of focusing on the top. If you want to be a future [university development] leader, you better be able to close big gifts. For small gifts, after two to three years there is a [career] ceiling.” Absent effort to change fundraising practice, as nonprofits focus on raising money from larger donors, efforts to raise small-donor donations can atrophy, accelerating the existing trend.

The Megadonor Trend Continues

Pruitt noted, “For many years, we tried not to talk about megadonors because that is not the average experience.” But she conceded that the trend has become harder to ignore: “Five percent of individual giving coming from less than 10 people is really of note.”

From a research perspective, Pruitt observed that even when donors post who they donate to, as MacKenzie Scott has done, the form of payment can be very unclear. “We don’t know if they are coming out of a DAF, charitable LLC [limited liability company], or foundation.” With Elon Musk, Pruitt said, researchers only became aware the fact that he had a charitable foundation due to a Securities and Exchange Commission filing for one of the companies he owns. “We don’t know what that is yet,” she added.

Advice for the Field

The focus of the Giving USA crowd is on how to raise money, not on the type of issues that NPQ might focus on—such as: Who controls the money? Or perhaps: Can philanthropy be a form of reparations?

When a question was posed about legislation to regulate DAFs, the response of all three panelists was to dodge. Pruitt noted, “We haven’t taken a policy position. We have some movement on the policy side and some legislation wanted to change the way DAFs are paid out. I think that the landscape has gotten really complex.” Dahlquist, for her part, said that “the policy questions will be asked and pursued,” but that her focus was to help her clients to raise the funds that they are seeking.

But on fundraising strategy, there was a clear recommendation. Simply put: What the megadonor giveth, the megadonor may also taketh away. In other words, don’t put all of your fundraising eggs in the megadonor basket.

Birkholz noted that reliance on larger donors is reinforcing a system of nonprofit “haves and have-nots.” Optimistically, Birkholz said that “there is the possibility to diversity and broaden your constituency.” He added that “it is not just the top places” where fundraising should focus if the goal is to achieve long-term sustainability.