April 6, 2014; Reuters

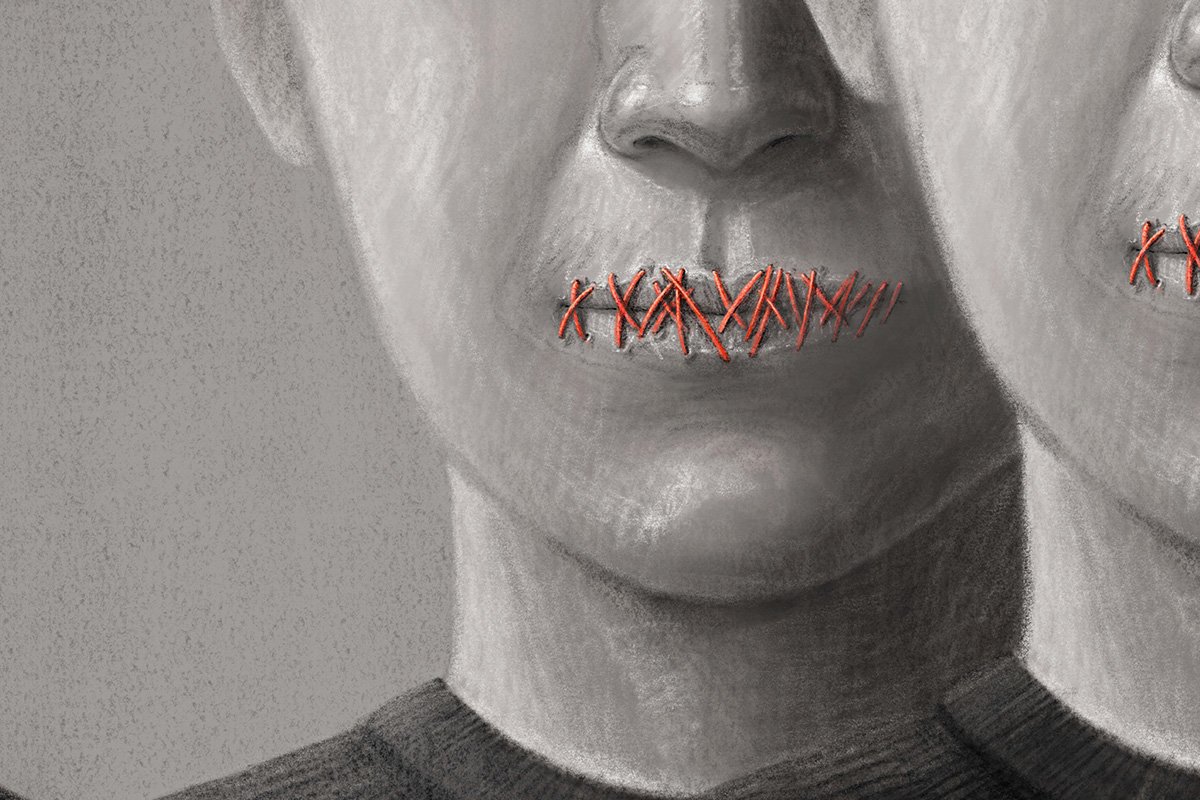

The University of Virginia is going to take action against Rolling Stone, which published a now-infamous article about an alleged sexual assault on its campus, though the frat is not alone in having suffered harm as a result of the piece. There are lessons and questions meriting public discussion in the Rolling Stone controversy, including issues for journalistic outlets large and small.

Now that the Rolling Stone article has been thoroughly discredited, the fraternity will likely claim that it was defamed by the article, that Rolling Stone editors published statements about the fraternity that were false, that Rolling Stone editors and the author of the article failed to check the facts that they published, and the fraternity suffered actionable harm as a result. A statement from the fraternity noted that Phi Kappa members were ostracized on campus after the article appeared, the fraternity house was vandalized with spray paint reading “UVA Center for RAPE Studies,” and UVA president Teresa Sullivan temporarily suspended fraternity and sorority social events in the aftermath of the original article. While UVA Phi Kappa chapter members are a discrete enough group to sue Rolling Stone for defamation, another group that has been harmed is too diffuse to do the same—the women who in the future will want to go to school authorities or local police with charges of sexual abuse but will fear, in light of “Jackie’s” repudiated assertions about the alleged Phi Kappa gang rape, that they won’t be believed.

As a result of the Columbia Journalism Review analysis, published by Rolling Stone itself on April 5th, of the now discredited rape story, there is much to be learned about journalism—and some things that aren’t quite clear but deserve public discussion.

Sabrina Erdely’s story, “A Rape on Campus: A Brutal Assault and Struggle for Justice at UVA,” published in Rolling Stone in November of 2014, became the magazine’s most viewed online story ever. Note that Erdely writes, or is supposed to write, deep investigative pieces that take a great deal of time for checking and rechecking sources and facts—she started working on the story in July of 2014, interviewing “Jackie,” a pseudonym used to protect her identity, seven times between July and October. A fact checker also had a long conversation with Jackie to verify the facts that Erdeley reported. In addition, there was apparently close oversight of the article by Rolling Stone managing editor Will Dana.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In the end, after all of this, there was nothing there but harm to everyone involved, though especially the women across the country who might be more vulnerable as a result of Jackie’s false charges and Rolling Stone’s undocumented writing. According to the CJR report on the story:

“The failure encompassed reporting, editing, editorial supervision and fact-checking. The magazine set aside or rationalized as unnecessary essential practices of reporting that, if pursued, would likely have led the magazine’s editors to reconsider publishing Jackie’s narrative so prominently, if at all. The published story glossed over the gaps in the magazine’s reporting by using pseudonyms and by failing to state where important information had come from.”

Rolling Stone claimed in its defense that it was trying not to re-traumatize the alleged rape victim by pursuing lines of inquiry that she didn’t want them to pursue, but that was only part of the issue—and doesn’t explain Rolling Stone’s journalist errors. According to the CJR article:

“The explanation that Rolling Stone failed because it deferred to a victim cannot adequately account for what went wrong. Erdely’s reporting records and interviews with participants make clear that the magazine did not pursue important reporting paths even when Jackie had made no request that they refrain. The editors made judgments about attribution, fact-checking and verification that greatly increased their risks of error but had little or nothing to do with protecting Jackie’s position.”

The actual CJR report is a very worthwhile read, and the Washington Post, which was one of the “independent” sources that first began poking holes in Erdely’s story (here and here) has an excellent summary of the report co-authored by Paul Farhi, one of the original Post critics of the Erdely article. It serves as a shorter alternative to the 12,000-word CJR piece.

In the wake of this story, there is enough to give us all pause, and suggest issues that journalistic outlets less prominent than Rolling Stone should be debating within their own ranks:

- Confirmation bias: “The problem of confirmation bias—the tendency of people to be trapped by pre-existing assumptions and to select facts that support their own views while overlooking contradictory ones—is a well-established finding of social science,” the CJR authors wrote. “It seems to have been a factor here.” We agree. The Rolling Stone author seems to have written expecting to—and wanting to—find a story about how UVA routinely mishandled reports of rape on campus facilities. All of us have to redouble the efforts to fight that tendency.

- Circulation bias: It reads to us like senior people at Rolling Stone read enough of Erdeley’s piece to know that it was going to get great readership. Rolling Stone founder and publisher Jann Wenner had read a pre-publication draft of Erdely’s story, calling it “powerful” and “provocative.” Targeting UVA at a time when just before a female student at UVA went missing was propitious timing. 2.7 million views for a Rolling Stone article is fabulous when the objective is online circulation, clicks, opens, pages read. It is journalism’s substitute metric for TV’s Neilsen ratings. Wenner told CJR that on reading the draft, he “thought we had something really good there,” but the journalistic red flags were waving all over it. An article likely to get robust readership needs double and triple the internal scrutiny if the counterweight is higher-ups salivating over likely “views.”

- Anonymity bias: Erdely gave her sources anonymity. Not just Jackie, who requested it as the purported victim, but others who she was under no obligation to keep secret, like the name of the alleged ringleader of the alleged gang rape. There are solid humanitarian reasons for keeping the names of rape victims out of the press, as is the policy in a number of outlets. However, there are many reporters who think that journalism has gone overboard with its guarantee of anonymity to alleged victims of rape, resulting in less than full reporting of cases and, like the Rolling Stone case, expanding the boundaries of what should be anonymous (like the name of Jackie’s alleged gang rape ringleader). Among the well-known writers who have questioned this practice is Geneva Overholser, who resigned her position as a Poynter columnist over Poynter’s unwillingness to name the alleged victim in one of her stories. It may be time for a debate over this controversial journalist practice, with persuasive arguments on both sides.

- And then there’s fact checking. Even though Rolling Stone has shrunk since its heyday, it still has resources for fact checking that the rest of us in journalism can’t imagine. It’s not simply a matter of solid proofing. It’s fact checking by people who can read a story and know what to look for that might need substantiation. As foundations nickel and dime nonprofit news outlets on the theory that somehow nonprofit journalism is less expensive to produce than mainstream journalism, journalism needs bodies—reporters to do the investigations and interviews and fact-checkers to double and triple check what might be wrong. The result for Rolling Stone isn’t that Edrely and Dana could have lost their jobs over a terribly flawed article. They didn’t and may not. But for Phi Kappa, it means a litigation process that may well cost the frat money in order to restore its reputation. And for women who are real victims of sexual assaults, it means a potentially greater load of suspicion that they may not be telling the truth.—Rick Cohen