July 1, 2015; Detroit News

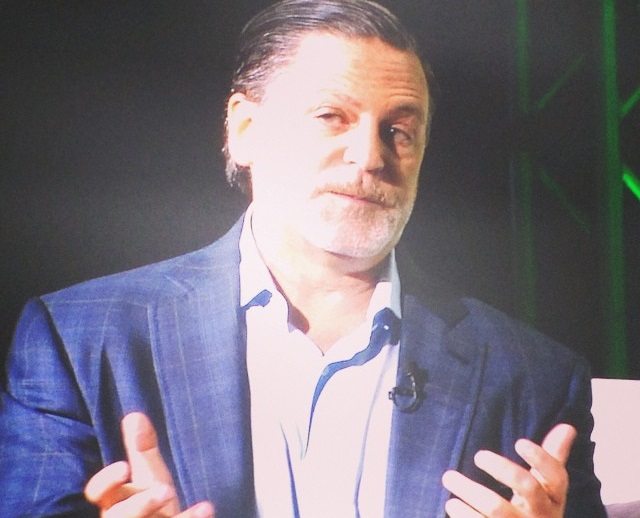

Dan Gilbert, the owner of Quicken Loans, has been lauded far and wide for investing in downtown Detroit and leading a revitalization undoing the city’s devastating blight. According to the Detroit News, Gilbert’s mortgage lending company may have been a significant contributor to blight by ranking fifth among all residential mortgage lenders in terms of the number of mortgages in Detroit that resulted in foreclosures during the past decade.

Detroit’s foreclosure problem is visible and massive. The article in the Detroit News says that that one of three homes in Detroit have been foreclosed in the city over ten years, equivalent to the entire housing stock of Buffalo, and costing the city $500 million, a figure The News came up with as a combination of the cost of demolition ($195 million) and lost tax payments ($300 million).

Detroit News reporters Christine MacDonald and Joel Kurth note that half of Detroit’s foreclosed properties ended up as blighted. Gilbert ended up co-chairing a task force of the Obama Administration that recommended 40,000 structures needed to be demolished. The implication is that the lending and foreclosure practices of Gilbert’s Quicken Loans were a major contributor to the City’s blight, without Gilbert’s acknowledgement that his company was a contributor to the problem.

They cite neighborhood leaders and the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan that Quicken was a significant contributor to Detroit’s blight. Brooke Tucker, an ACLU of Michigan attorney, said there is “no question” Quicken’s large number of foreclosures over the past decade contributed to Detroit blight though other financial institutions were worse, and added “I wish banks would spend more funds like Dan Gilbert to try to fix the mess, but they do have a responsibility for the mess. This is a bank-driven, mortgage-driven problem.” The News reported that just short of one-fourth of Quicken mortgages in Detroit could be considered “subprime.” Gilbert challenges the News characterization of Quicken loans as subprime as erroneous. Guy D. Cecala, CEO and publisher of Inside Mortgage Finance, told The News that “Quicken would argue their track record was better than anyone in the industry, but of course the bar isn’t that high in the mortgage industry.”

Bernard Parker, an east side activist and former Wayne County commissioner, said that Quicken was more aggressive than other companies in selling mortgages before the national economic meltdown. “Quicken, along with other banks that gave these loans, have some responsibility to rebuild neighborhoods,” said Parker, who now runs the Timbuktu Academy of Science and Technology charter school. “No one thinks Dan Gilbert is a friend or champion of the neighborhoods” around his east side neighborhood, he added.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

MacDonald and Kurth name four other firms with more foreclosures in Detroit than Quicken. Argent Mortgage/Ameriquest Mortgage, Washington Mutual, New Century Mortgage, and Countrywide all beat Quicken in foreclosures, but all four went out of business during the mortgage meltdown, while Quicken survived and seems to have thrived.

Gilbert, you might say, is unhappy with the Detroit News report, contending that his company’s lending policies cannot be authoritatively linked to the city’s widespread blight: “It’s very hard to make any causation between these loans and the fact that (homeowners) walked away or could not afford the payments and some eventually became blighted,” Gilbert told The News. Gilbert doesn’t seem to take criticisms or investigation with equanimity. Earlier this spring, the federal government sued Quicken alleging that the company had approved lots of mortgages between 2007 and 2011, though with no specific mention of Detroit, that didn’t meet federal standards, but Gilbert responded that the feds were on a “witch hunt” and filed a pre-emptive suit against the U.S. Department of Justice.

Distinctively, Gilbert said that it wasn’t his company’s mortgage loans or perhaps even other mortgage foreclosures that were responsible for the blight. “I’m sure some lenders contributed to part of it,” Gilbert said. “But No. 1, I’d have to say, is property taxes. … That was like throwing gas on a fire.”

On a conservative radio talk show, Gilbert called MacDonald and Kurth “irresponsible” and “unprofessional” . Although MacDonald is an adult, Gilbert said that she had seemed to be a “pretty smart girl”. It’s not as bad as having called LeBron James “narcissistic,” “callous”, “cowardly,” “heartless,” and worse when James left Gilbert’s Cleveland Cavaliers in 2010, but it is, by now, quite clear that Gilbert doesn’t appreciate being crossed in the press or in sports. The investigative press has gotten on his last nerve. Gilbert clearly took aim at journalism in his radio show comments, saying “Someone needs to hold these muckracker [sic] people accountable.”

Gilbert and Quicken have their supporters in this dynamic. Steve Bancroft, the former Dean of the Cathedral Church of St. Paul in Detroit who served as executive director of the Detroit Office of Foreclosure Prevention and Response from 2008 until 2011, told The News, “Quicken is probably more responsible than most.” However, like the other banks, Quicken, according to Bancroft, said, “We’re sorry this happened to the city, but we didn’t do any bad loans.”

Does the Quicken foreclosure controversy have any meaning for nonprofits and foundations concerned about the revitalization of Detroit? A few obvious implications could be these:

- Gilbert has been hailed as something of a savior of downtown Detroit, buying up enough downtown office properties that some call it now “Gilberttown.” It shouldn’t be surprising that the philanthropic (and non-philanthropic) saviors of troubled communities may not have totally clean hands regarding community problems. Quicken may not have been the worst of the mortgage lenders, but it was part of the mix in Detroit. Gilbert’s idea that high property taxes rather than mortgage foreclosures led to blight in the late 2000s runs counter to the nation’s experience of the mortgage meltdown. Detroit—and everyplace similar—should be careful when they turn over some of the thinking about aspects of their problems, such as Gilbert’s role in leading the blight task force, to players who might have had a role in creating or sustaining the problems.

- Cities such as Baltimore and Memphis sued banks over the decrepit conditions of their foreclose properties, but that didn’t happen in Detroit. Efforts to hold banks and mortgage companies accountable for the conditions of properties really didn’t happen. According to Steve Tobocman, the former co-director of the Michigan Foreclosure Task Force and former member of the Michigan House of Representatives, “There’s an ironclad correlation between subprime lending and abandoned, blighted and in-need-of-demolition houses in Detroit…We had an opportunity to move forward on some of those homes and abuses, and we didn’t take that opportunity.” Although Detroit unlike almost all other cities had a foundation-funded foreclosure prevention office, the city didn’t or couldn’t generate the muster to go after the banks in court to mitigate some of the blight that their foreclosures, regardless of Gilbert’s contentions about property taxes, may have contributed to. Activists long pressured the city to go after the banks on foreclosures, and there was word that the city’s former corporation counsel and a deputy mayor drafted a plan to sue predatory lenders, but former mayor Dave Bing said that he was never presented with a proposal, though Bing also noted that his focus was on making payroll and paying city expenses rather than pursuing risky court litigation. However, Bancroft, at the foundation-funded foreclosure office, which reported to the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation, said that the city didn’t want to risk alienating potential investors. “If you act precipitously and go at them hard, you’ll never see another mortgage in the city,” Bancroft said. It would appear that the kid glove treatment of the mortgage foreclosing lenders didn’t quite work.

- The mortgage foreclosure problem was worse in Detroit than in much of the rest of the country. More than two-thirds of mortgages in Detroit, according to The News, were subprime, compared to a little over one-fourth statewide and a little less than one-fourth nationwide. A 2008 report written by this author for the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University documented the “persistent, disparate racial impacts of the subprime lending crisis.” The subprime lending and subsequent foreclosures that swamped Detroit are hard to ignore for their racial implications. The revitalization of Detroit isn’t just a matter of bailing out public pensions and “saving” the Detroit Institute of Arts as the foundation community has done through the “Grand Bargain” or regionalizing the management of Detroit’s water and sewer authority, but recognizing and dealing with the racial roots of the city’s problems and the reparations of sorts that the institutional perpetrators, through their omissions or co-missions, should be making.

In the words of MacDonald and Kurth, “(F)oreclosure is a bomb with multiple detonations. The first comes when homes are abandoned. Then they are neglected, stripped of metals, left open for squatters and drug dealers. When nothing is left, they often burn.” In Detroit, once attractive neighborhoods are full of abandoned, devastated homes, awaiting the bulldozer as recommended by Gilbert’s blight task force, rather than rehabbers who might have saved the properties hadn’t it been for the city’s—and the nation’s—mortgage foreclosure crisis. It is easy to see that compared with the likes of Countrywide, Gilbert’s Quicken Loans would have been hard-pressed to be at the top of the worst lenders in Detroit. Nonetheless, despite his slurs against the two “muckrakers” at The News, Gilbert might benefit from some greater sense of contrition and Detroit might benefit from being a little more wary of corporate saviors.—Rick Cohen