This is the third installment of a five-part series, Reclaiming Control: The History and Future of Choice in Our Health, examining how healthcare in the US has been built on the principle of imposing control over body, mind, and expression. However, that legacy stands alongside another: that of organizers, healers, and care workers reclaiming control over health at both the individual and systems levels. Published in five monthly installments from July to November 2022, this series aims to spark imagination amongst NPQ‘s readers and practitioners by speaking to both histories, combining research with examples of health liberation efforts.

Imagine with me, for a moment, that when you feel physically, emotionally, or spiritually unwell, your first stop is a nourishing, natural space. It envelops you in warmth and the familiar scents of the herbs, that possibly your grandmother grew. The healers that greet you deeply understand your social history because the structure of their work allows ample time for listening. They, alongside you and members of your community, have built deep relationships through participatory workshops that have enabled all to have a direct say in the services and traditions that are offered. The guidance offered in this space reflects collective understanding of the costs to health imposed by oppressive systems, and harnesses expertise in the practices and rituals your ancestors relied on to survive. Bodies and identities of all kinds are accepted, nourished, and encouraged to play—rather than restricted or controlled.

Across the country, our current healthcare system addresses sickness with sterile clinic rooms, excruciating wait times, rushed visits, overworked staff, and discriminatory systems.

This is a dream, unfortunately, and far from reality. Across the country, our current healthcare system addresses sickness with sterile clinic rooms, excruciating wait times, rushed visits, overworked staff, and discriminatory systems. In the first two articles of this series—Reclaiming Control: The History and Future of Choice in Our Health—we delved into how the legacies of white supremacy, profit maximization, and patriarchy have shaped our existing healthcare system. We examined how many organizers and movements are wading into what appears like the nightmare of transforming a system that is massive and technically complicated. This installment in the series turns to—another set of actors: those seeking to actualize dreams by building alternative models centered in collective visions for healing.

These organizations, often led by women and nonbinary people of color, offer pathways to health based on a dramatically different set of values and approaches than the traditional medical care complex. Some of them are embedded in the healing justice movement, which was named in 2007 by the Kindred Southern Healing Justice to honor a history of BIPOC, queer, trans, and disabled communities looking to ancestral healing practices in order to address generational trauma from systemic violence. Drawing upon ancestral wisdoms, as well as present-day insights, they choose to center liberation, rest, communal support, autonomy, and more—rather than the medicalization-first approach that dominates in the US.

These models explore systems disruption at multiple levels: individual, institutional, and systemic levels. At the individual level, these entities radically design care around the person, rather than forcing individuals to conform to a predetermined course of care. Founders of and participants in these models also prioritize epistemological diversity, pulling from ways of knowing that exist outside of western, white-dominant spaces. In doing so, they are testing how remedies passed down within cultures for centuries may be particularly effective for addressing conditions related to trauma and stress. They are also acknowledging that, since our mainstream healthcare system emerged from conditions that frequently exploited and denied the rights of oppressed communities, it is useful to understand how those communities practiced healing and well-being.

At the institutional level, these organizations are challenging existing governance and organizational structures for health: many of them, for example, follow cooperative or collective models in which healers and members exercise ownership over the strategy, operations, and revenue generated. In this way, these organizations are not only providing a different approach to healing, they are also creating new organizational structures within which that healing can take place. If one of the major challenges of the existing way that control manifests in the healthcare system is removing choice, then these structures demonstrate what it looks like for people to be actively involved in decision-making about the services, investments, and management that comprise health.

And while these organizations may be most frequently focused at the place-based level, where they can engage communities directly, many of them are also linked at the systems level to movement spaces that are fighting for a number of shifts, from corporate accountability to worker conditions to Black maternal health. These connections can happen on two levels. First, by recognizing that political and social forces directly impact wellness, these organizations often bring this power analysis to their work. And, second, many are also focused on actualizing a healing justice framework—informed by economic, gender, racial, reproductive, and disability justice movements—to ensure the role of healing inside of movement environments.

Alternative Approaches Centering History and Autonomy

Founded in 2014, Harriet’s Apothecary is a collective of healers, health professionals, activists, and others that “self-organizes to center healing, wellness and resilience without relying on the medical industrial complex, while also taking health institutions to task about how they create safer and thriving spaces for BIPOC people.” The group centers a Black, queer, feminist analysis that acknowledges the root causes of marginalization and violence, and prioritizes affordability, accessibility, and honoring all bodies and genders.

The programming and services offered through the organization speak to this specific analysis, spanning a wide variety of formats and objectives. Their healing villages, for example, supports the BIPOC community’s healing from stress and trauma, by offering a broad set of healing offerings ranging from plant-based medicine making to somatics bodywork, thai yoga massage, herbalism, and more. These villages are intended to cater to people who may find other healthcare settings harmful or unsafe.

In addition to these direct services, Harriet’s Apothecary provides political education and leadership training focused on enabling participants to examine the challenges of the traditional medical care system, and to develop storytelling and tools related to indigenous methods of wellness and care. Via community workshops and skillshares, the organization focuses both on movement-building and equipping participants with rituals and practices they can bring back to their own communities, schools, and families.

In Baltimore, the Village of Love and Resistance (VOLAR) was co-created as a self-sustained, cooperative community space for health and wellness. Founded in East Baltimore—where residents and communities have long grappled with historical harms driven by healthcare systems—VOLAR seeks to reclaim land, foster healing, and build a base of community power.

The organization has raised funds to purchase buildings that will be transformed into healing spaces and facilities, including a community wellness center, a small business incubator for Black and Brown-led healing enterprises, and a community organizing academy. To enable reclamation of land in a place where Black and low-income community residents have often faced barriers to property ownership, the organization is using a community investment trust fund model that will provide low-dollar investment opportunities to existing residents, and ensure that they can take part in the redevelopment of their own neighborhood rather than experiencing gentrification.

In addition to co-creating and sustaining community-led spaces for healing, some organizations are also bringing their unique healing systems and frameworks, as a point of discussion, to other places where people of color are grappling with questions related to health. Black Womxn Flourish is a design-for-wellbeing collective that utilizes collaborative, community-led spaces, visioning, and healing-centric experiences to shape the future of Black womxn’s health. In a year-long collaboration with Living Cities, the organization developed and facilitated co-design sessions for the Closing the Gaps network, a gathering of anti-racist organizers convened in collaboration with Living Cities.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The sessions were designed to center the wellbeing of Black women leaders who are asked to hold racial equity work for their organizations. They were rooted in a pro-Black vision for the future and sought to answer:

- How might we cultivate life-giving environments where the full promotion of Blackness can flourish?

- How might we integrate healing justice practices into racial equity work that fortifies the minds, bodies, and spirits of Black women?

- How might we protect Black women’s personal and creative agency as they lead transformative work within their communities?

Specifically, the organization used P. Ife Williams’ “creative healing praxis,” which delves into how Black joy and creativity is related to healing relationships. By centering compassion, imagination, and holistic perspectives, the sessions generated both recommendations and creative manifestations of wellbeing.

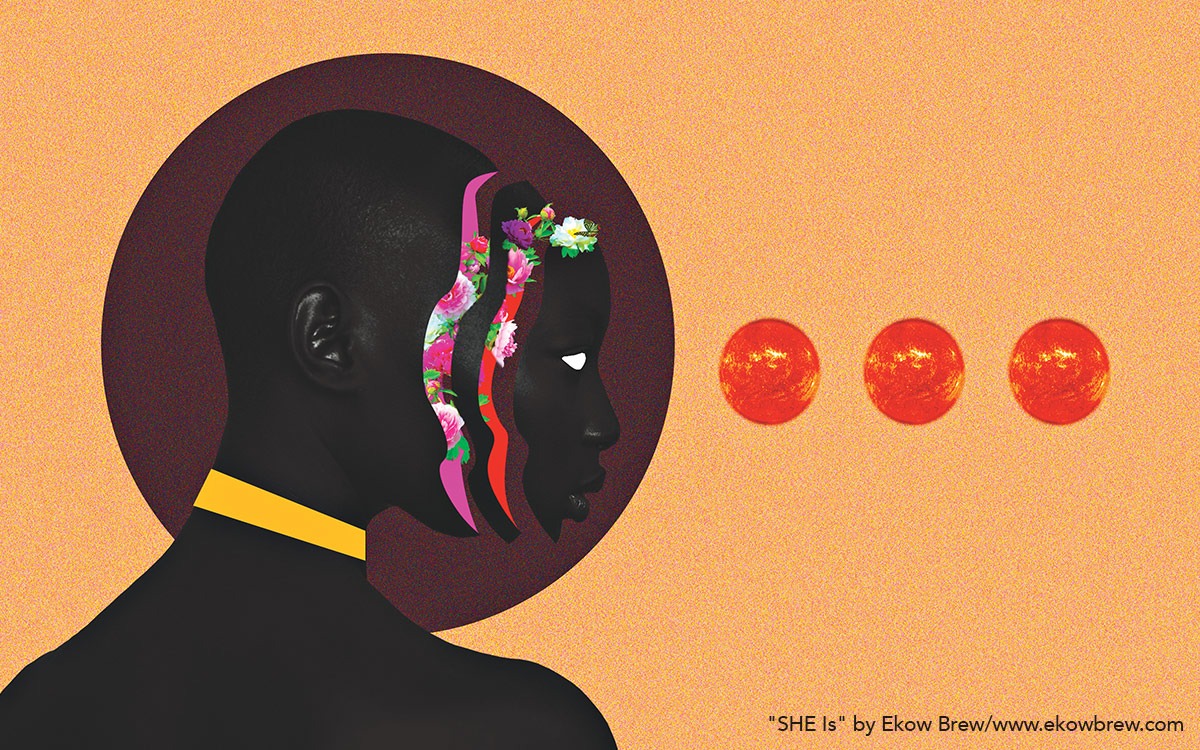

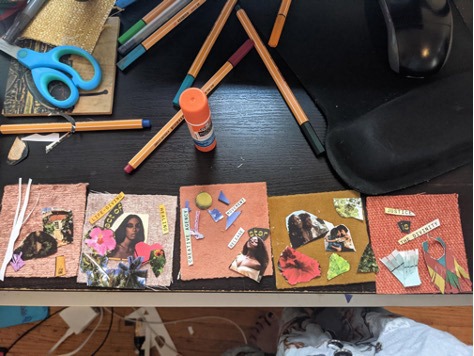

Figure 1: Artwork from Closing the Gaps sessions

Dream spaces are particularly crucial to organizations that are working to re-envision and create multiple paradigm shifts at once.

Denise Shanté Brown, founder of Black Womxn Flourish, describes the role of imagination in their organization’s work, including the development of Dreaming Flourishing Futures: A Black Womxn’s Manifesto for Designing the Worlds We Must Have to Be Well, to be released this fall: “In 2020, when we felt an ever-present call for audacious leaps of imagination to propel us towards a future in which we are all free, we extended invitations to our community to gather virtually… participants moved through a generative journey of somatic exploration and guided visualizations rooted in Black Imagination, collective collaging, affirmation writing, and the creation of artifacts from a Black womxn’s flourishing future from the chosen years of 2025 to 9262.”

Dream spaces are particularly crucial to organizations that are working to re-envision and create multiple paradigm shifts at once. New Seneca Village is a recently launched initiative that seeks to bring together BIPOC cis, trans and nonbinary leaders and healers via pilot residencies that provide space for healing and reflecting. Ultimately, the effort seeks to secure a large piece of land as well as a $110 million endowment that will enable the transfer of that land to a community-governed, mission-driven land trust. New Seneca Village is intended to center connection to a natural, nurturing environment that enables both social justice leaders and healers to gain some respite from their leadership roles and engage in collective visioning, skills exchange, and as described in the organization’s year one update: “a line in the sand against the ongoing, burnout-inducing nonprofit system, and a bulwark against the potential loss (actual or psychic) of these strong leaders from organizations and movements that survive because of their expertise and dedication”.

The first year of the effort convened leaders and healers from across the country, but rather than focusing on professional purpose and planning for the community, participants instead spent time simply relationship building and “being.” Going forward, an advisory circle as well as those who have been part of the New Seneca Village community to date will also engage in collective visioning to shape the village ecosystem and future direction.

The noise—and size—of the wellness industry can often obscure the importance of models that truly are rooted in community responsiveness and the efforts of practitioners whose work is that of systems change rather than sales.

Ain Bailey, founder of New Seneca Village, shares how healing and imagination are intertwined: “So many women—and I’ve had my own organizational trauma—have this same story…in a nonprofit calling, we’re looking and saying, we could do better; lives could be changed. But then the [traditional] spaces organized around that are so resistance to change and transformation, rather than trying new things in a way that is abundantly resourced and all-in. That then pulls us deeper into work that is not always grounded in our own vision and sovereignty. Instead, let’s adopt an abundance framework and live into that as much as possible, because that is the baseline state of this planet. How do we practice that?”

Visioning Into the Future

One challenge that exists alongside these alternative models—that are deeply rooted in ancestral practices which enable BIPOC communities to thrive—is the proliferation of a commoditized wellness industry that often appropriates those practices and packages them for white, upper-class audiences. The noise—and size—of the wellness industry can often obscure the importance of models that truly are rooted in community responsiveness and the efforts of practitioners whose work is that of systems change rather than sales.

Another challenge is that models that prioritize community responsiveness require an enormous amount of investment and effort from their founders and communities. Because they are designed to present alternatives to a massive set of systems, those who are engaged in them carry the burden of identifying how the work is supported, funded, and grown. As they do so, they frequently face significant skepticism and resistance to the viability of their visions. Furthermore, many of those who can seek care within these alternative spaces may still have to interface with the traditional medical care system, whether for their own wellness or in the role of a caregiver. In these cases, the distinctions between a healing space and a medical industry space can be jarring.

Yet, despite the challenges, these organizations continue to dream—connecting the ancient to the present, co-designing rather than paternalizing, and soothing trauma rather than exacerbating it. Their stories light the way forward to imagine what could be.