February 4, 2019; Columbia Journalism Review and the New York Times

The mayor of Dearborn, Michigan, seems to have learned none of the lessons from the many leaders of states, cities, and public institutions who have had to confront the difficult parts of history—in particular, how they remember and memorialize incidents of bigotry and hatred, like the legacy of the Confederacy. When recently confronted with Henry Ford’s legacy of virulent antisemitism, John B. O’Reilly chose to stonewall and stick his head in the sand rather than recognize the importance of coming to grips with even the disturbing parts of our historical record.

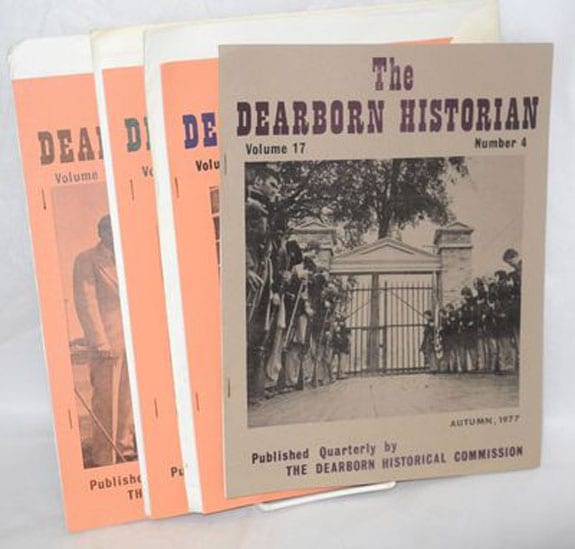

A hundred years ago, Henry Ford used a paper he owned, the Dearborn Independent, to publish what the Columbia Journalism Review described as an “anti-Semitic 91-part series called The International Jew.” The civic-owned, nonprofit Dearborn Historian decided to publish an edition exploring this upsetting topic. In return, the publication was squelched.

Part-time editor Bill McGraw thought it appropriate to use the quarterly publication of the city’s historic commission, with a circulation of less than 300, to explore this part of Ford’s legacy. One of McGraw’s motivations for composing the 11-page article was how seminal the long-running screed remains for today’s white-supremacists and anti-Semites. Ford is mentioned “hundreds of thousands of times” in online white supremacist forums, and new recruits to the movement see Ford’s fame as lending credence to his beliefs: “Hey, look at this incredible American, this global celebrity: he thinks like us.”

The city and its historical commission would be doing an important, educational service by not letting this part of Ford’s legacy remain in the shadows. But Dearborn’s mayor saw the magazine only from the narrow perspective of a potential PR problem. Upon receiving a pre-publication copy, Mayor Jack O’Reilly had all printed copies of the magazine recalled and locked away. The city’s public information officer released a statement that explained the reasoning behind this action.

We want Dearborn to be understood as it is today—a community that works hard at fostering positive relationships within our city and beyond. We expect city-funded publications like The Historian to support these efforts. It was thought that by presenting information from 100 years ago that included hateful messages—without a compelling reason directly linked to events in Dearborn today—this edition of The Historian could become a distraction from our continuing messages of inclusion and respect. For this reason, the Mayor asked that the distribution of the hard copies of the current edition of The Historian be halted.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

McGraw, who was working under contract and not an employee, was summarily removed from his position.

Rather than keep the unpleasant side of Ford’s legacy under wraps, however, the mayor’s act taught a familiar lesson: the futility of trying to keep secrets in a hyper-connected world. The quashed article was published online in Deadline Detroit and several other publications, and the New York Times covered the story of its suppression in its Sunday edition.

Jonathon Stanton, the historical commission’s chairman, told the Times, “It is just really important to emphasize that history is looking at the whole picture. If we’re only talking about the parts that make us proud, then what we’re doing isn’t really history. Now, instead of Dearborn confronting its past, people are talking about how the city is reluctant to discuss history.” In the end, the mayor, who has been seen as a strong advocate for the diversity of Dearborn’s population, has left his supporters confused.

A young resident of Dearborn, Kareem Ali, when interviewed by the Times, expressed the lesson that Mayor O’Reilly and every other leader faced with similar challenges can learn from this controversy: “It does nobody any good to censor this kind of thing. I’m against hate towards anyone, and it’s important to remember history because it reminds us that just because you’re rich and famous doesn’t mean you’re a perfect person. Everyone has flaws.” And retired teacher Edward Markey asked, “What does it accomplish to pretend that this isn’t a part of Henry Ford’s story? He should be respected for what he did and condemned for his shortcomings. Many geniuses were also terrible human beings. That’s kind of a good lesson about people, isn’t it?”

Given a chance to pull the skeletons from Ford’s closet and highlight that Dearborn has grown well beyond those times, the city’s actions have left it with a self-inflicted injury. It now becomes a lesson for others to benefit from. History cannot be expunged or papered over; it’s there to be embraced, both good and bad.—Martin Levine