It is hard to believe that November 3rd is just over a month away. This election season has been distinguished by the degree to which other issues have competed for the public’s focus. Therein lies a problem in the form of a relatively low rate of voter registration—understandable in the context of the pandemic but shocking in terms of what is at stake.

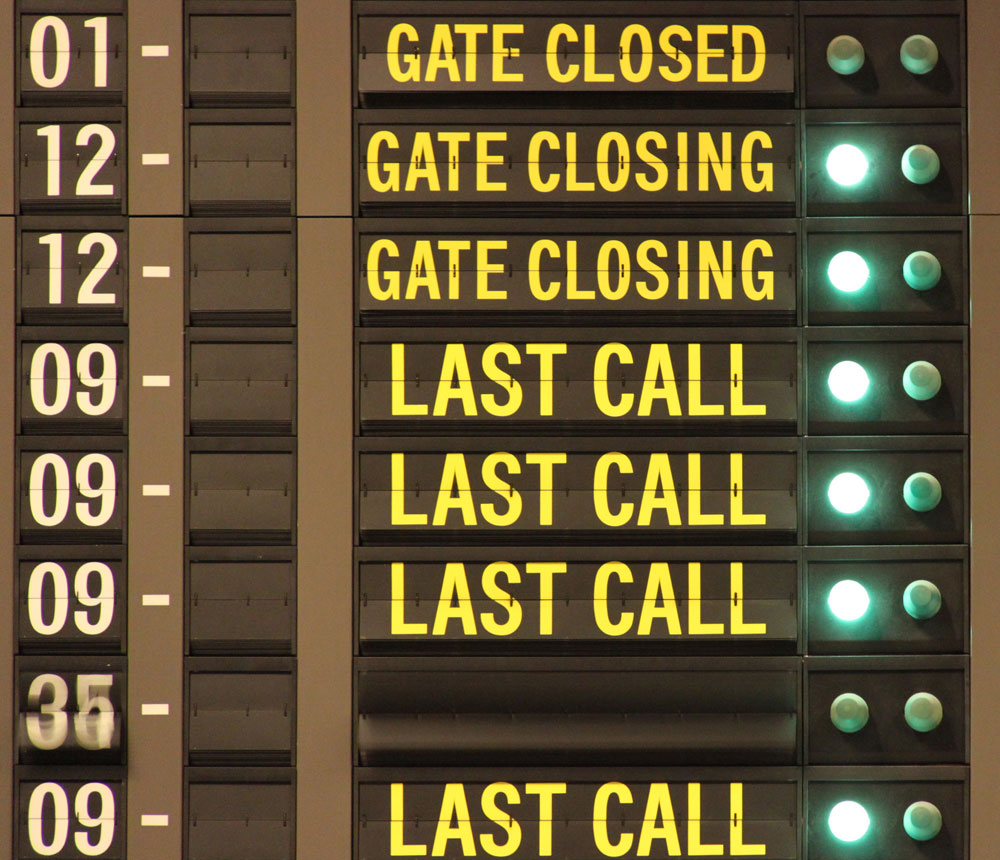

So, we write this editorial as a last call to nonprofits. Remind all of your stakeholders to register this week, because the window is, in many cases, closing fast.

In the midst of everything else this year, you could be forgiven if you have not been following voter registration numbers. Last week, we published an article that observed a surge in voter registration in the wake of the recent death of US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the unseemly politicking around her replacement.

This surge is encouraging, but it also called our attention at NPQ to something else: namely, the recent surge is hiding what has been a decline in voter registration numbers. Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic has interrupted many voter registration efforts, even if many states have tried to accommodate by, for instance, making registration possible online.

This is important. As we detail in a chart at the end of this article, many states have voter registration deadlines that start showing up on October 4th—that’s this Sunday. In short, for some states, this is the last week you have to register voters. Others have more accommodating deadlines. It is all very complicated; when we looked at state registration laws, we realized that if you look at all of the deadlines, the 50 states have election deadlines of some type on 20 different days in the month of October.

The voter registration challenge facing us is made clear in a brief published by the nonprofit Brennan Center for Justice last week. To come up with their numbers, Brennan Center researchers compared the pace of registration in 2020 with 2016 in 21 states. The analysis concerned only those states that “make monthly counts of registered voters available on the website of the relevant chief elections officials.”

There were some bright spots. Registration was up in four of the 21 states analyzed: Alaska, Idaho, Michigan, and Utah. But only one of these—Michigan—could reasonably be considered a battleground state. The other 17 show lower registration rates. In Wisconsin, a key battleground state, registration is off by only a modest two percent. But other potential presidential swing states have seen more significant declines.

What counts as a swing state, of course, can be disputed, but consider the following seven states—six of which were carried by a presidential candidate in 2016 who won less than 50 percent of the popular vote and one of which (Iowa) was carried by Barack Obama in 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016.

Degree of decline in voter registration pace (2020 versus 2016)

| Arizona | -65 percent |

| Colorado | -20 percent |

| Florida | -26 percent |

| Iowa | -39 percent |

| Nevada | -32 percent |

| North Carolina | -14 percent |

| Virginia | -24 percent |

Voter registration matters—a lot. In 2016, according to the Pew Research Center, 86.8 percent of US registered voters cast a ballot in the presidential election.

Let that number sink in for a second. The United States is legendary for its low-turnout elections. But as a percentage of registered voters, US turnout is actually among the highest in the world. According to Pew, if you only look at registered voters, the US in its most recent general election had the fourth highest turnout of 35 countries, exceeded only by Luxembourg, Australia, and Belgium. But in terms of overall eligible voters, the US falls far lower. In 2016, only 58.7 percent of eligible voters cast ballots.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

As we observed at NPQ earlier this year, while political analysts and campaigns focus on winning over the “moderate” or “independent voters, turnout matters far more.

Consider how many analysts debate whether Jill Stein cost Hilary Clinton the election, which, a Politico article published a few months ago claims, still “haunts” her campaign team. Yet her team is oddly not haunted by the far larger number of voters who did not cast a ballot at all. The number of voters who cast ballots for Barack Obama in 2012, but sat out 2016, was 4.4 million. Jill Stein only got 1.457 million votes—that’s one-third as much.

A study by the Knight Foundation on 100 million nonvoters published early this year, pointedly noted that if you included “did not vote” in the popular vote count, the 2016 presidential election would have looked as follows:

| Did Not Vote | 41.3 percent |

| Hillary Clinton | 28.5 percent |

| Donald Trump | 27.3 percent |

| Other | 2.9 percent |

If 86.8 percent of those who registered to vote did so, yet only 58.7 percent of eligible voters cast ballots—that tells you something. Most directly, it tells you that three in ten eligible voters (32.4 percent, to be precise) had not registered to vote. Put differently, of 100 million nonvoters in the US, at least 70 million were not on the voting rolls.

And, if you read the Knight study carefully, you’ll find many chose not to register and not to vote well in advance of Election Day. There are, of course, deep problems with US politics that have developed over decades. If we are honest with ourselves—and that Knight study documents this—there is deep disillusionment among many nonvoters. For many nonvoters, it is a conscious decision not to register and not to vote. If nonprofits and community-based groups wish to persuade these people to engage, it will require deep relationship-building and organizing.

Of course, conscious choice is hardly the only reason why people do not register to vote. Too often, voter registration rules are part and parcel of a system that seeks to suppress votes—especially those of Black Americans, indigenous communities, and people of color, as NPQ has covered.

The bottom line: While get-out-the-vote efforts are important, making sure people have registered to vote is a critical first step. Even in those states where same-day registration is permitted, as the data show, the very act of registering to vote often doubles as the setting of the intention to show up and vote—whether by mail, early voting, or on election day.

In any case, please don’t wait until Election Day! That, of course, is especially true this year, when some have voted already, and many are likely to vote early or by mail.

Even if your nonprofit does not engage in election outreach per se, there are simple steps you can take—from emailing your membership with links to your state’s voter registration site to putting voter registration information and links on your website, to old-fashioned customized outreach, such as calling key stakeholders.

Below, based in large measure on charts published by Bloomberg, we provide a simple picture of what different states’ rules are. But please also check websites like vote.org, which includes links to voter registration in each state.

Time is short. Act now!

Summary of State Voter Registration Rules

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| * Mail deadline in Vermont is recommended to ensure receipt by election day. |