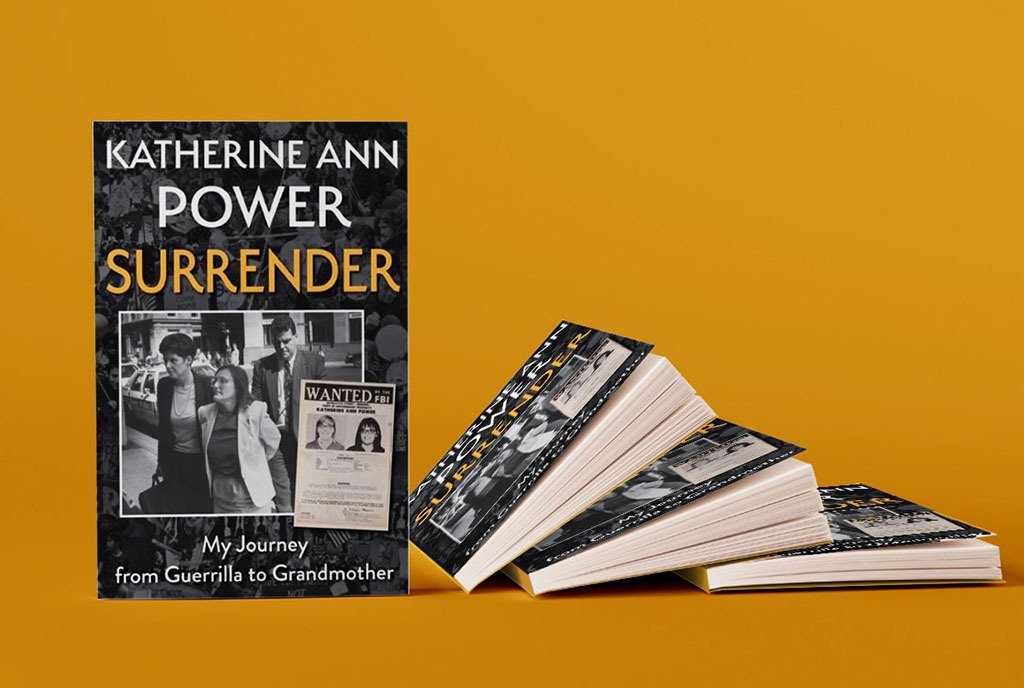

As a student at Brandeis University, Katherine Ann Power became a leading organizer in what became known as the National Student Strike Information Center. This excerpt is from her memoirs, Surrender: My Journey from Guerrilla to Grandmother (Practical Peace Publishing, 2023). The book details her movement trajectory, including her subsequent involvement in the Weather Underground and an armed robbery that led to the killing of a police officer; her 23 years as a fugitive; her negotiated surrender; and her post-prison reflections on resistance, nonviolence, and social change.

This section, taken from the book’s second chapter, recounts part of her transition from being an idealist and nonviolent activist in the US movement against the Vietnam War to becoming an urban guerrilla.

Reprinted here with author and press permission.

One day I heard, as we sat around a table in the classroom, “All the Vietnamese want is to farm their lands and fuck their wives.” Wait. What about Vietnamese women? I thought. What do they want? Do they count? I might have been the only female in the classroom, but I had always seen myself as a peer of the male students. I took that equality so for granted that I had never expected to have to argue that women counted as people too.

All the wars since Vietnam have been sanitized to keep us from seeing [military violence] this clearly again.Months earlier, when one of the women invited me to join the women’s liberation group that was starting on the campus, I told her no. I said I was a strong woman and didn’t need a group. Now I began to doubt that all the personal strength I might ever muster would penetrate that wall of the men’s non-seeing of women.

I remember sitting at the same table in that same class about Vietnam, learning the names of the US weapons and what they did: flechette, a bomb that exploded a thousand razors out into flesh in every direction. Napalm, jellied gasoline that stuck to the skin, a burning from which there was no escape. Phosphorus that burned white hot, so hot that it seared to the bone in the instant of contact. Free fire zone, where every moving human was considered an enemy, fair game for snipers overflying in small planes. Agent Orange, the poison that killed jungle cover and food crops (and which would persist and sicken Americans and Vietnamese for generations). Carpet bombing, no need for explanation. Land mines, phantom weapons that lie in a farmer’s field, to explode decades later.

How could I not commit my whole self to making it stop? Even now, I occasionally doubt myself. I wonder if my reaction was extreme. Was the war really not that bad? I have only to open Nick Turse’s Kill Everything that Moves to any page at all to be reminded that murder, torture, rape, home burnings, and forced displacement were everyday acts of the US military during the Vietnam War and that these acts came from policies dictated at the highest levels. All the wars since Vietnam have been sanitized to keep us from seeing it this clearly again.

On April 30, 1970, [President Richard] Nixon announced that he had expanded the war, sending gigantic B-52s to drop 25-ton payloads on Cambodian villages and towns and planning to send in ground troops.

That news was the no-going-back moment from the politics of rage for me and tens of thousands. We had never believed Nixon’s campaign promise to end the war. But such was our naïve faith in democracy that we had not imagined that he would plot secretly to defy democratic processes and expand it. In a mighty explosion, students all over the country gathered spontaneously, demonstrating and closing down campuses. Our goal was to stop business as usual, to stop the war by making it impossible to carry it on.

The strike exploded further when, on May 4, National Guardsmen fired into a crowd of protestors at Kent State University in Ohio. They killed four students and seriously wounded twelve more. The Newsweek cover image of a screaming woman kneeling next to the dead body of Jeffrey Miller was captioned “Nixon’s Home Front.” Days later, city police and highway patrolmen in Mississippi fired hundreds of rounds of live ammunition into a crowd of demonstrating students at Jackson State, a historically Black college. They killed two students and wounded dozens more.

Many of the students who went out on strike had never identified as militants, but the killing of students by uniformed soldiers shooting live ammunition from M-1 rifles changed that. There was a widespread sense that the government had escalated its repression into a shooting war. Being at war, then, became, for some—myself included—our model of change.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Seven hundred schools shut down, waiving final exams or making them optional, and then closing for the summer.

The strike was a grassroots upwelling of dissent that had been building for years, but the strength of the strike itself was sustained through a powerful, informal communication network. This network arose in part because 15,000 people were gathered in New Haven on the weekend of the bombing announcement to protest the jailing of Black Panther Bobby Seale on murder charges (charges that never resulted in conviction but that kept Seale incarcerated for two years). All weekend long, we held meetings to plan our next actions around what became the three issues of the student strike—the government’s repression of dissent, the Vietnam War, and university complicity with the military.

There was little appetite for central organization of the emerging protests, but we knew a communication network was necessary. We could not depend on the media to tell us how big the strike was growing, and we wanted to be able to share the best tactics as they emerged. The Brandeis contingent, confident that we would be allowed to use resources on campus, offered to act as a clearing house to help this happen. We gathered contact information, and as people scattered back to campuses where strikes had already begun, they started to report in. The National Student Strike Information Center was born.

Back at Brandeis, we set up operations. With no internet, cell phones, Twitter, or Facebook; the taking in, aggregating, and reporting back of news and information to hundreds of sites was quite a process. We communicated over Ham radio, broadcasting our phone number and asking people to call in and report. We set up phone lines and used the university’s WATS line (precursor to unlimited long-distance and 1-800 numbers) to place calls. Dozens of volunteers answered calls and took handwritten notes on half sheets of paper, printed with purple ditto machine ink. Was your school on strike? Were they signed on to all three issues? What percent of students participated? Were faculty striking too? Did the administration support or obstruct the strike effort?

We…spread the information through phone trees, the 1970 version of re-tweets.

Reports poured in of hundreds of colleges and dozens of high schools striking, of the bombing of a military recruitment center or an ROTC building every single day. Over two million students went out on strike. Seven hundred schools shut down, waiving final exams or making them optional, and then closing for the summer.

We hand-tabulated the notes and reported the number of colleges and high schools on strike in a daily phone call to five contacts around the country who spread the information through phone trees, the 1970 version of re-tweets. We published a weekly newsletter on what was then the state of the art in self-printing, a Gestetner mimeograph machine. It grew rapidly to sixteen tabloid-size pages, and we had to send it out to be printed.

I threw myself into the activity, answering phones, organizing workflow, and running the mimeograph. Because I was fierce and articulate, I often spoke to the press. We prided ourselves on developing a system of leaders who did not act like stars, reminding reporters of this when they did interviews. But when La Prensa, the Cuban national newspaper, called and asked for me, I did feel like a star.

Sandy, a good friend from that time who later visited me in prison, reminded me of what it was like then. She asked me if I remembered that she had forcibly led me out of the Strike Center and insisted that I get some sleep. I did not, nor did I remember most of what happened in those frantic weeks of writing, cutting, pasting (literally), and mailing the Strike Center Newsletter. Many of the students involved report having little memory of those weeks as they worked frantically, organizing strikes and demonstrations nationwide. I am sure some of that was sheer exhaustion. But I wonder too how much resulted from the fury with which we entered into the work, the totality that ending the war had become in our minds.

Even when schools closed for the summer, there was plenty for the Strike Center to report on. We continued to publish the newsletter, adding news of lobbying campaigns in Washington, GIs sabotaging the war, and Black Panther Party free medical clinics. Brandeis was one of a dozen schools that kept campuses open for “Resistance Summer.” About a hundred students engaged in all kinds of political activity in addition to the Strike Center lived in one dorm. Its communal kitchen was vegetarian and kosher.

For me, it was a summer of great camaraderie and purpose. I had now realized, like so many other students of the time, that continuing in school in pursuit of a career was no answer to a world on fire.