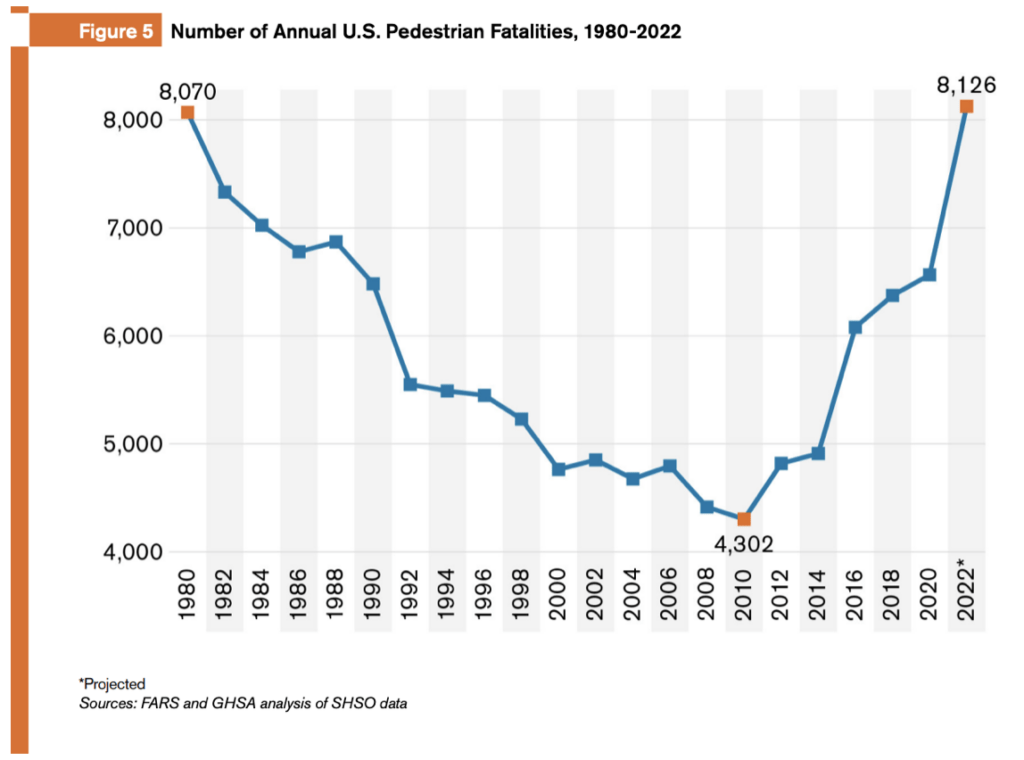

Pedestrian deaths in the United States have surged, reaching numbers unseen not just in the past few years, but in decades.

Pedestrian deaths rose by about 54 percent between 2010 and 2020.

The number of pedestrians struck and killed by vehicles reached—and then surpassed—a 40-year high in 2021, according to the latest national data released by the Governors Highways Safety Association, a nonprofit representation of US state and territorial highway safety offices. The organization closely tracks traffic and pedestrian fatality data. And digging deeper into the numbers yields more alarming statistics.

Overall, pedestrian deaths rose by about 54 percent between 2010 and 2020, from about 4,300 to over 7,600. As a portion of all traffic deaths, pedestrian fatalities have gone over the past decade from about 13 percent to 18 percent. Since 2018, the percentage of pedestrian fatalities among children younger than 15 in which speeding was a factor has doubled.

Those national numbers belie even more deadly trends in some individual states. Between 2021 and 2022 alone, pedestrian deaths increased by 77 percent in New Hampshire; by 60 percent in Nebraska; by close to 50 percent in Wisconsin and Oregon; and by about one-third in Virginia, Massachusetts, and Kentucky.

These fatality rates represent an almost-uniquely American trend, at least among other wealthy and developed nations. Overall, Australia, Japan, Israel, Korea, Chile, Columbia, and all of Europe have reported significant downward trends in pedestrian fatalities over roughly the same period that the United States has seen them rise (along with, to a lesser extent, the United Kingdom).

“There is a pedestrian safety crisis on our roads, and it’s only gotten worse since the start of the pandemic,” said GHSA Chief Executive Officer Jonathan Adkins in a press release.

What’s more, behind the raw number of pedestrian deaths are some of the racial and economic disparities that underlie so much of US society: lower-income people and people of color are significantly more likely to be victims of fatal pedestrian crashes.

These fatality rates represent an almost-uniquely American trend.

A Preventable Crisis

The dramatic difference between rising pedestrian fatalities in the United States and declining numbers across most of the rest of the Global North points to a somewhat obvious conclusion: that many, perhaps even most, of these deaths are preventable.

And the solutions, say advocates, are clear and actionable.

“Oftentimes people want to somehow or another blame the behavior of drivers or pedestrians,” says Mike McGinn, executive director of America Walks, a nonprofit dedicated to making the United States safer for pedestrians. “But that ignores the real underlying cause, which is the dangerous design of our roadways, and that vehicles are getting larger and more dangerous as well.”

Put simply, says McGinn, road design and car design are both the problem and the solution to one of the most preventable public health crises in the United States.

“I think traffic deaths, in general, are just sort of taken for granted and not looked at as a social problem or a public health problem that’s really solvable,” says Angie Schmitt, transportation writer, consultant, and author of Right of Way: Race, Class and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America, which argues that pedestrian deaths represent a racist, classist, and profoundly preventable public health disaster.

“We do have a lot of levers we can employ that we have strong confidence will save a decent number of lives that we routinely just choose not to employ,” Schmitt notes.

Those solutions are often relatively straightforward and common-sense, including better roadway markings and signage, more crosswalks, better traffic signaling, traffic-calming measures like speed humps and stop signs, and more aggressive measures like “road diets,” in which traffic lanes are reduced to create more space and safety for other roadway users, including pedestrians.

According to experts, the problem is not a paucity of solutions; it’s a lack of will to implement them—to change the status quo as it has existed now for decades. The design standards always centered on how many cars you move and how fast you can move them, with safety standards taking a backseat, as it were.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“What we’ve done in this country is we’ve taken local streets and we’ve brought highway design principles to them: wider lanes, more lanes, few crossings,” says McGinn. “And you know, what that leads to is places that are very hostile to people outside the vehicle, to pedestrians…. And that’s where the deaths occur.”

A Question of Political Will

If solutions abound to the pedestrian fatality problem, why aren’t they being implemented in communities across the country?

One clear answer is what might be called American car culture, which is the cultural and political resistance to any changes that negatively impact cars and their drivers.

“You see often a segment of the population getting very upset if they perceive that any roadway space is taken away from driving for things like traffic calming or bus lanes or bike lanes,” says McGinn. “And unfortunately, too many people, too many politicians respond to that, believing that those loud voices represent the majority. They do not.”

McGinn believes that most residents of a given community do want safer streets, but that their voices are drowned out by louder, and often more powerful ones—usually belonging to wealthier, often Whiter constituencies.

“Let’s be really clear, those who drive a lot are usually better-off people who have more power,” says McGinn. “Commuters coming from more expensive homes and who can afford downtown parking oftentimes have more political weight than the Black and Brown or immigrant and refugee communities that are being driven through.”

“It comes down to people with power making intentional decisions.”

Meanwhile, McGinn says, “People who live in those communities have far higher rates of pedestrian deaths than White communities because the roads are less safe and more people have to walk.”

Another major factor in the rise of pedestrian fatalities, as well as an obstacle to reducing them going forward, is the state of the American car industry. As Schmitt notes, “Cars are getting bigger, with more aggressive front ends.”

For decades now, the American auto industry has been producing and aggressively marketing larger vehicles, with the share of drivers in SUVs and pickup trucks rising drastically.

While the auto industry has denied it, and federal regulators have been largely mute on the question, a growing abundance of evidence points to a direct link between the trend of larger vehicles and rising pedestrian deaths. A 2020 study by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee found that since 1980 the percentage of pedestrian deaths associated with larger vehicles like trucks and SUVs doubled.

“It comes down to people with power making intentional decisions,” says Schmitt. “I think the auto companies really deserve a lot of blame, but our regulators have not been willing to…rein them in the way they should.”

Despite headwinds, advocates like Schmitt and McGinn see paths forward.

Many US cities, Schmitt notes, have adopted so-called Vision Zero policies which state goals of eliminating traffic fatalities, and some have even put funding and expertise behind them to implement traffic calming measures, many of which prove relatively easy—in terms of engineering as well as politics—to put in place.

“In a lot of cases, some of the things we need to do wouldn’t be that controversial,” says Schmitt. “There just hasn’t been any focus on doing it.”

McGinn, meanwhile, is convinced that in most communities, residents who want safer streets outnumber those who don’t—and that there is power in those numbers. “In my mind, there’s no question that the movement for safer, more walkable, more accessible places is growing,” says McGinn. “But there’s a hell of a lot of status quo inertia to overcome.”