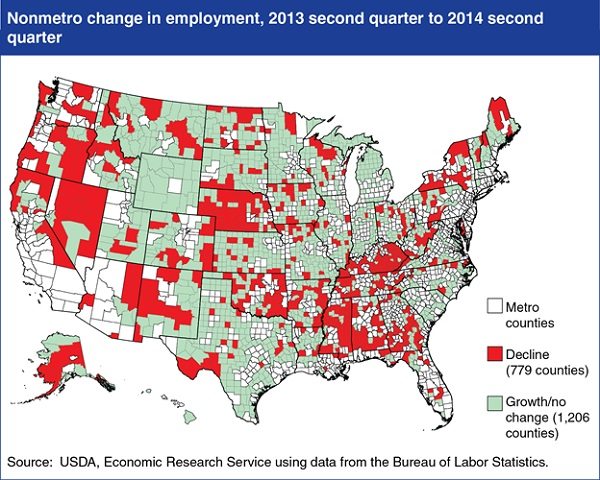

In the USDA’s Rural America at a Glance, a compilation of social and economic indicators about conditions in rural America that was issued just last month, there’s a map on job growth that’s telling: It shows that rural areas are far behind metro counties in their recovery from the depths of the recession and the gap continues to grow.

Source: USDA http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1704714/nonmetro-change-in-employment.png

Rural employment growth would have lagged further if it weren’t for the job growth in the 114 rural counties where oil and gas extraction more than doubled between 2000 and 2011.

The report includes a number of other social and economic indicators, but one big one is missing: the inflows and outflows of charitable dollars in rural America. There have been many efforts over the years since the fruitless challenge of then-senator Max Baucus (D-MT) to get the foundations that make grants to rural America to double their grantmaking in five years. As with many other efforts to nudge charity and philanthropy toward greater focus on social goals, Baucus’s initiative, without the use of his power on the Senate Finance Committee, accomplished nothing other than a couple of rural philanthropy conferences and a glossy book distributed by the Council on Foundations.

What has happened to rural philanthropy? With scant resources and weak data, we have been doing our best to examine slices of philanthropic support for rural America, beyond what might be grantmaking to entities in nonmetropolitan areas that don’t actually use the funding for anything particularly rural—other than themselves.

In 2004, in a report called Beyond City Limits, we documented what looked like a philanthropic spending level of less than one percent dedicated to rural community and economic development. Some years later, that report was followed by another on Rural Philanthropy, drawing on focus groups in rural areas of California, New Mexico, Florida, Kentucky, Montana, Mississippi, and Texas, revealing how nonprofits in these areas were struggling with a lack of both local and national philanthropic support. In 2011, we at NPQ documented a decrease of 3.45 percent in rural development granting, despite a huge 43.4 percent increase in overall foundation grants between 2004 and 2008. In 2013, we looked at foundation grantmaking to the top 67 rural CDCs as reflected in their prominent as grantees of Rural LISC or identities as Rural NeighborWorks groups, and found that when PRIs and other non-grant assistance was removed from the calculations, these top-notch groups had seen sizable decreases in their foundation support in 2010 and 2011. For 93 Rural LISC and NeighborWorks groups, their non-governmental support between 2009 and 2011 dropped 12.6 percent.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

//

Summarizing other reporting we have done on rural philanthropy comes out roughly the same, a picture showing that the philanthropic resources devoted to rural America have not kept up with the moneys flowing to metropolitan and suburban locales. No one should think that philanthropy is doing a bang-up job in urban areas either when it comes to issues of community development, poverty, and affordable housing, but the data, even if limited, make it clear that, just like in job creation, rural is falling behind in its access to philanthropic grants.

With these statistics, one might think that there might be a national crisis concerning institutional philanthropy’s bypassing of the social, economic, and housing needs of rural America. At a rural philanthropy conference sponsored by the Council on Foundations in 2011, the USDA signed a memorandum of understanding with the Council, whose purpose Agriculture described as, “to provide new sources of capital, new job opportunities, workforce investment strategies, and identification of additional resources that can be used to spur economic growth in rural America.” It isn’t clear exactly what ensued between the USDA and the foundations’ trade association to implement the MOU they signed, perhaps because the results might not have shown much of an increase in philanthropic giving to rural, but Secretary Vilsack this past July created a “foundation” within the department, the Foundation for Food and Agricultural Research, a 501(c)(3) public charity to seek and accept private donations, both individual and foundation, to fund research of national significance. It does not appear that either the USDA or the Council on Foundations has conducted any sort of assessment of the cooperative venture to determine if philanthropy did generate new sources of capital for rural economic development.

In the meantime, the National Rural Funders Collaborative has shut down. An assessment report about the NRFC experience published in 2012 was a dispiriting read, with its conclusions that conveyed a hope for regional and issue-based collaborations to succeed the national program, the likelihood that future rural funders will fund more narrowly than their predecessors, and that funders might put particular emphasis on the development of community philanthropy in rural areas. In both the NRFC analysis and in other reports, including a report by the Points of Light Foundation and the Volunteer Center National Network, an emerging emphasis played to rural self-reliance and called for increased attention to volunteerism in addition to—or subtly in place of—turning to philanthropic support, even though the case studies highlighted by Points of Light were clearly connected to foundations: a healthcare access project in Abingdon, Virginia, that benefitted from support from the Virginia Healthcare Foundation, and Cass Lake’s effort for comprehensive community revitalization getting support from one of the Minnesota Initiative Foundations through the foundation’s Healthy Communities Program. The notion that volunteerism replaces philanthropy in modern life is a pleasant and seductive trope used by both government and foundations in their mythification of rural America’s self-help, mutual aid tradition, but it’s a non-starter about real life. Rural communities and rural nonprofits need resources and cannot be expected to compete based on assumptions that rural people simply volunteer for each other, work for significantly less pay when they are employed to do community work, and carry out multiple jobs when comparable organizations in metropolitan areas are permitted, encouraged, and funded to recruit people to do one job at a time.

In 2011, the Appalachian Regional Commission allocated $1 million to support community philanthropy in Eastern Kentucky which it then followed with a March 2012 “consultation” on what might be done to vault community philanthropy. After repeating the much-cited research about the impending intergenerational transfer of wealth that could be captured for rural philanthropy, the consultation called for the collection and dissemination of examples of effective partnerships between development organizations and community foundations, the identification of models for collaborative funding, building the capacity of community foundations, building relationships between community foundations and local development districts, and developing metrics to measure community foundations’ impact. Raising new money for regional funds attached to community foundations is another positive concept, indicative of the bootstrapping image of many rural communities, but remarkably slow and hardly likely to provide capital comparable to the kind of grantmaking from a foundation like Z. Smith Reynolds, which created and funded the MAY Coalition to promote business development and provide loans for entrepreneurs in Mitchell, Avery, and Yancey counties in North Carolina, to cite one example. The Coalition is a certified Community Development Financial Institution and provides loans as high as $250,000, hardly likely for a community foundation trying to endow a new regional fund.

Neither the ARC nor the USDA have taken aim at the nearly $1 trillion in foundation endowments to ask, much less influence, why more of that isn’t flowing into rural communities and rural nonprofits. It is an unavoidable issue; if the question is philanthropic assets devoted to rural development, indigenous assets captured through a rural piece of the intergenerational transfer of wealth are important to go after, but their accumulation will be slow and tedious, and if devoted to endowments, generating only a five percent actual expenditure toward rural causes. Rural philanthropy needs the big foundations to weigh in and put concentrated resources into domestic rural programs. However, despite all the discussion of rural philanthropy during the past decade, as documented above, the philanthropic trend seems to be going against rural.

- The big leadership foundations are not stressing rural: Some still maintain significant rural grantmaking portfolios, but the grantmaking for domestic rural issues is sometimes quite limited and the staff that were not only dedicated to rural, but seen as leaders in rural philanthropy are no longer there. At the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s website, a search for rural brings up 50 hits covering grants and news stories stretching back to 2012, but a significant if not dominant proportion of the grants that are specifically rural are international and not domestic. Kellogg maintains some historically important rural grantmaking, notably its continuing support for the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium’s Dental Health Aid Therapists program and for the Center for Rural Strategies’ rural advocacy. At the Ford Foundation, while there are staff tasked to the issue of climate change strengthening rural communities, there doesn’t appear to be a specific domestic rural portfolio, as there once was. While there are good people in many foundations, including Kellogg and Ford, who care deeply about rural America, the profile of rural in U.S. institutional philanthropy is receding. One top foundation executive has been widely reported to have said that the best thing that can done for rural people is to give them bus tickets to cities. That certainly doesn’t at all reflect the grantmakers who lead rural stalwarts such as the Northwest Area Foundation, the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, the F.B. Heron Foundation, the California Endowment, the McKnight Foundation, the Charles Blandin Foundation, the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation, and the Otto Bremer Foundation, but when it comes to philanthropy writ large, the commitment to rural development appears to be fading.

- There is no big rural philanthropy advocate: When Max Baucus issued his challenge to philanthropy, Kellogg had a vice president for rural development, Rick Foster, who was seen as a national leader in the field. A counterpart program director at Ford is also no longer there. We think that there are some foundation leaders who can and should be speaking out broadly and forcefully to their peers about the need for rural philanthropy, but it takes a personality and commitment including a willingness to call out other foundations. Just after Kirke Wilson left the Rosenberg Foundation in 2010, he wrote directly about what foundations knew and didn’t know about rural communities and how their knowledge hampered rural philanthropy. He cited the perception that somehow rural groups are too government-dependent and thus threaten foundations’ desires to remain independent of government and other challenges, but laid the responsibility at the foundations’ door: “Most foundations remain as unreceptive to rural organizations and rural issues as they were a decade ago. While it is essential that rural advocacy continue within the field of philanthropy, the next phase of work will require the leadership of rural organizations to address, indirectly and incrementally, the obstacles to foundation support of rural organizations. This will entail deliberate and long-term commitments to building networks among rural organizations and the intermediary organizations that serve them while challenging misperceptions, stereotypes and other obstacles to rural philanthropy.” We know of others who were once major and visible rural philanthropy advocates but have become quieter in recent years. With foundations moving in reverse on rural, it will take a rural champion willing to pull few or no punches in telling foundation peers exactly how they are falling short.

- There is a lack of government accountability: When the Appalachian Regional Commission and the USDA announce philanthropy programs, they have to be called to account to report on what their initiatives achieved—and if they didn’t achieve what they should have, what needs to be done next. This isn’t happening, as too many philanthropy advocates give wide berth to governmental intervention in the field. But that has to happen, just as it should have happened (and didn’t) with former Senator Baucus, to demand that he report on what he and his staff did to push foundations to double their rural grantmaking. Philanthropic advocates tend to be fearful, to put it mildly, of unleashing Congress to act on philanthropy, concerned that their interest might find root in the tax-writing committees that could restructure tax treatment and IRS oversight of philanthropy, a sleeping dog that many nonprofits would rather let lie. Foundations talk about public-private partnerships, new and stronger linkages with federal and state agencies, and even incentives for philanthropy such as tax credits and capacity building for community foundations, but it is one-way—what foundations want from government, not what government or the public need from philanthropy. Even if there isn’t going to be legislation, and there honestly probably won’t be, rural advocates need to pick up on the theme that Rep. Xavier Becerra (D-CA) has consistently raised, that foundations ought to be examined for what they are delivering to address critical social problems of poverty. If foundations cannot be encouraged to see rural as a specific need, then members of Congress like Becerra could be encouraged to ask what foundations are delivering and should deliver to areas of poverty. It is well known that nonmetropolitan poverty exceeds metropolitan poverty in every region of the nation and that 85 percent of the 353 persistently poor counties in the U.S. are rural. Foundations need to be called to account on who benefits more and who benefits less from philanthropic distributions.

- Economic development is failing to count philanthropic resource flows: The USDA’s Rural America at a Glance report reveals an important shortcoming. In its collection of social and economic indicators, the USDA report doesn’t mention philanthropy, even though many accounts of economic progress in rural communities have foundations at their roots. Our social and economic intelligence is missing—in urban as well as rural areas—information about the use and distribution of foundation resources. The need is for more than a meta-review of the proportion of all philanthropy that reaches rural development. It needs to be taken down to regional and even local levels. So much of U.S. philanthropy is rooted in rural assets and resources, but there is never an accounting that examines how much of this capital flows out of rural and how little flows into specific regions. This could and should be a government function, perhaps even a function of a state’s charities bureau or a state economic development department. Why would governments be reluctant to do this? It isn’t justifiable. This is a resource, and government ought to know how it is reaching—or not reaching—critical needs in the state’s communities.

Ultimately, the need is for philanthropic advocacy, but nonprofits tend to be next to petrified about the notion of organizing about philanthropy and about linking that organization with public policy. Even the nation’s strongest philanthropic advocates have receded in their willingness to pursue advocacy in the public arena concerning philanthropy. Somehow, for every aspect of society, nonprofits are willing to challenge, organize, and advocate, but when it comes to foundations, the presumption of foundations’ being on the side of the angels gives them a shield no other sector gets. Unless and until rural communities are going to be satisfied with demonstration grants, foundation conferences, and glossy books, rural philanthropy doesn’t have good prospects of increasing in the future.