August 31, 2017; Washington Post

Most know the last week in September best as bringing the start of autumn. However, for book lovers and First Amendment aficionados, it’s also the time for the national weeklong celebration of books that have been banned. In Washington, D.C., home to the world’s largest library, the Library of Congress, the District’s public library system is planning an eye-opening treat for interested residents.

The Public Library Foundation, the library’s fundraising arm, hid 600 copies of six books—The Giver, Fahrenheit 451, The Handmaid’s Tale, Parable of the Sower, We, and Who Fears Death—around greater D.C. and challenged residents to locate them. As part of this year’s theme, “Texts Against Tyranny,” these titles feature settings or societies where books are restricted or banned, and some themselves have come up for restriction or censure. Lucky residents who find a copy will get a special edition to add to their collections. However, book sleuths who locate a copy of all six titles will find that the covers combine to form a special hidden image. The covers are devoid of anything except quotes, disguising their true nature to onlookers as a reminder of the ways readers of the past would disguise banned literature behind false covers so they would not be caught.

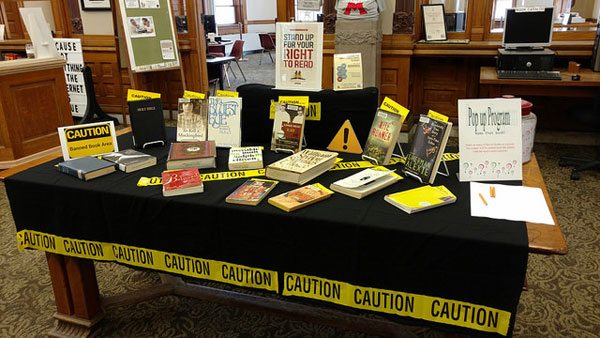

Banned Books Week is an opportunity for the book-loving community—readers, writers, publishers, librarians, and teachers—to acknowledge their victories in the fight to preserve the right to read. It is also an annual call to action and fundraising opportunity to support the effort of groups and libraries facing book challenges. In some communities, the restriction of books remains an issue, though it’s less a problem in the United States than in other countries.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Some question whether Banned Book Week serves a purpose at all. Critics contend that book banning in the U.S. is a nonexistent problem since the Constitution prohibits the official “banning” of books. Instead, these “challenges” are meant to stop a particular school from teaching a book, or a specific library from carrying one. As a result, they believe the week unnecessarily calls attention to the dead practice and calls into question the First Amendment rights of those acting in opposition to certain texts out of a sense that parents have the right to determine what is age-appropriate for their children and what they should be allowed to read.

Another view, as espoused by Ruth Graham in her 2015 Slate article, “Banned Books Week Is a Crock,” is that the national sponsors of the annual week are “fearmongering.” According to her research,

The ALA maintains an interactive project, “Mapping Censorship,” that displays cases of book bans and challenges across the United States (and a few stray cases overseas) between 2007 and 2012. I clicked through all 290 examples and found 27 cases that likely concerned public libraries as opposed to school libraries or school curricula. (The descriptions aren’t always clear, but when in doubt I erred on the side of assuming a library was public.) Of the 27 cases in which a book was challenged at a public library, the ALA documents a whopping four cases that definitively ended with a book being completely removed from circulation. There are likely more, of course, but suffice it to say there is no tidal wave of censorship inundating our nation’s libraries.

That is good news, and we’d venture that no one in the community appreciates this data more than the American Library Association, the major sponsor of Banned Books Week. But, as some elements of 2017’s society attempt to police thought, speech, race, dress, gender, and religion, perhaps it’s not so bad to remember the threat. Maybe one of the quotes from the special edition banned books, hidden in the very appropriate location of Washington, D.C., is the famous one about knowing history so it won’t be repeated.—Mary Frances Mitchner