May 30, 2014; Newsweek

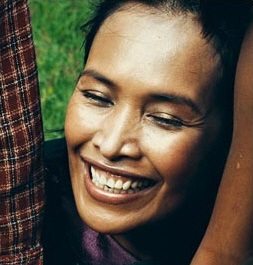

This week at the Council on Foundations, a session is scheduled to feature the Somaly Mam Foundation. Somaly Mam, in case you do not yet know, is a Cambodian woman who has been traveling the world to raise money to prevent sex trafficking. Her own story of being an orphan sold into slavery herself is excruciating—and it also appears to be, at least in part, untrue.

Perhaps this story by now is beginning to sound all too familiar, with shades of Greg Mortensen and Lance Armstrong, both similarly lifted up as heroes around which charitable foundations have been built. Similarly to those two examples, Somaly Mam has now resigned the foundation that bears her name.

The Somaly Mam foundation boasts some heavy celebrity ballast on its board—Susan Sarandon, Angelina Jolie, Hillary Clinton, and Meg Ryan, as examples—and as supporters. Mam was on Time’s list of its 100 most influential people in 2009 and she has 400,000 followers on Twitter. She has spoken at the White House and addressed the UN.

Left behind is a cover story by Simon Marks in Newsweek with a headline that reads “Sex, Slavery & a Slippery Truth.” It alleges that Mam not only falsified part of her own story but that she put other young women up to telling false stories of forced prostitution and that she vastly overstated the parameters of the problem in Cambodia.

As the reporter for this story put increasing pressure on Mam to answer questions, the foundation hired a law firm to conduct an independent investigation not only into Mam’s story, but also into the stories girls associated with her organization had told publicly. In its statement, it not only announced Mam’s resignation but the severance of ties with one of those girls. The statement read:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“In March, the Foundation retained the law firm Goodwin Procter LLP to conduct an independent, third party investigation into allegations concerning the personal history of Somaly Mam and Somana (Long Pross). The Foundation provided Goodwin Procter unfettered access to our information, documents, and staff, and, for the past two months, a team of Goodwin Procter legal professionals based out of Boston, San Francisco, and Hong Kong conducted an extensive investigation.

“As a result of Goodwin Procter’s efforts, we have accepted Somaly’s resignation effective immediately. In addition, we are permanently removing Ms. Pross from any affiliation with the organization or our grant partner, but will help her to transition into the next phase of her life. While we are extremely saddened by this news, we remain grateful to Somaly’s work over the past two decades and for helping to build a foundation that has served thousands of women and girls, and has raised critical awareness of the nearly 21 million individuals who are currently enslaved today.”

Pross told Oprah Winfrey and Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times that she was kidnapped and sold into slavery, was beaten and had her eye gouged out before Mam rescued her. The Newsweek article reported that Pross had actually come to the center to participate in a vocational training program, and she had surgery on her eye to deal with a nonmalignant tumor.

There is no doubt that sexual slavery is a serious problem and that, ironically, Mam’s work has helped to lift the issue up, but there have been indications that her story had problems long before this. Marks writes in Newsweek that:

“Experts in sex trafficking say that while it is a serious problem, the scale and dynamics of the situation are often misunderstood, in part because of lurid, sensationalistic stories such as those told by Mam and her ‘girls.’ In 2009, 14 organizations and academics, including George Soros’s Open Society Foundations, wrote a letter to Salty Features, an independent film production company based in New York, to thank it for its interest in making a film about Mam’s work in Cambodia.

“But they advised against having the documentary focus on Mam due to AFESIP’s lack of understanding of the sex industry. In an interview for Euronews in 2012, Mam said girls as young as 3 are being held in Cambodian brothels. Experts in the field say that is almost unheard-of. Patrick Stayton, who formerly ran the Christian, faith-based International Justice Mission (IJM) in Cambodia, says, ‘They may have had a supply of younger girls between the age of 14 and 17,’ but adds, ‘We’ve never seen prepubescent girls, or very, very rarely.’”

How much damage might this do to this movement? We hope not much, but we also hope that it does damage the deification of human beings as personal embodiments of a movement. While it sometimes works, in many cases, it does not, instead creating wariness and skepticism in the public sensibility.—Rick Cohen