Last December, in Upper Darby, an 85,000-person suburban community outside of Philadelphia, many residents, when they entered “hospital” into their map app and rushed to their local hospital to seek urgent medical care, found that the emergency room—and indeed the entire Delaware County Memorial facility—had closed.

Far from unique, this story is horrifyingly familiar. Why? Private equity—that is, investor groups that operate outside of the stock market, thus being largely shielded from public investor scrutiny—plays a leading role. Understanding the role private equity is playing in health care is critical; only then can we begin to design solutions to the healthcare system that center public and community ownership.

A Growing Menace

In the US, a staggering $4.3 trillion is spent on healthcare (18.3 percent of the entire US economy and growing), a per capita level of expenditure that is far higher than any other developed nation, yet health outcomes are poorer. Where does all this money go?

There are many villains (think, for example, “Big Pharma” and insurance companies), but a growing driver of these high costs are private equity firms and the rapacious financialization they pursue. In recent years, private investors have been buying hospitals, nursing home chains, and other key healthcare institutions, squeezing out their profits, saddling the institutions with debt, then dumping these now distressed “assets” back into the community.

By way of comparison, in 2000, annual investments by private equity firms in healthcare averaged around $5 billion. In 2021, that number was $206 billion, as reported by Kaiser Health News—enough to purchase 1,400 hospitals and other healthcare firms. Over the past decade, total private equity investments in healthcare have approached $1 trillion, accounting for nearly 8,000 healthcare facility acquisitions.

These purchases can have devastating impacts on the quality of healthcare. Many healthcare facilities are held by private equity firms for three to five years after acquisition, during which time the firms extract as much money as possible from the businesses before selling them. After such profit optimizing, many formerly private equity-owned hospitals and clinics close or go bankrupt.

The hospitals are left with unpayable debt, while private equity investors make off like bandits.

Indeed, it is now all too common to open up the newspaper and read horror stories about private equity forays into the nursing home industry, emergency room care, dentistry, or specialty care, like gastroenterology and anesthesiology. These tales tell of healthcare “investments” that decimate local health systems—increasing mortality and morbidity rates—saddle patients with ever larger bills, and deprive the healthcare workforce of stable, fair working conditions. Private equity is responsible for the invention of “surprise billing” and for “obstetric emergency departments” that bill standard births as if they were unexpected, complicated emergencies. It continues to “innovate” new ways of draining the healthcare sector of essential resources.

Take Delaware County Memorial, which was acquired by Prospect Medical, a private equity-owned group of hospitals that has to date closed five of the 20 facilities it purchased, including in Upper Darby, where the closure means that city residents now lack a local hospital. According to CBS News, Prospect Medical’s system for extracting profit is not complicated, but it is certainly exploitative. The Los Angeles-based investor group saw that it could purchase Philadelphia suburban hospitals, take out a $1.12 billion loan against those businesses, pay themselves $457 million in dividends (including a $90 million bonus for the CEO), then sell the land and buildings that the hospitals owned to a third party for $1.386 billion, saddling the hospitals with $35 million in annual rent on the land they now must lease. In short, the hospitals are left with unpayable debt, while private equity investors make off like bandits.

Due to these actions, Prospect Medical is currently facing litigation—perhaps these efforts will succeed in reopening the hospital in Upper Darby. Many communities are not so lucky.

Why Private Equity Is Parasitic to Health

Private equity ownership of nursing homes both upped their Medicare billings and increased patient mortality by 10 percent—translating to over 20,000 lives lost across [a] 12-year period.

Through these extractive practices, private equity ends up being parasitic—whisking dollars away from healing and caring and into the finance, investment, and real estate sector (or FIRE) to make money for shareholders.

The hospital in Upper Darby illustrates this, as it faced a new annual cost of $35 million a year for rent—up from a baseline of zero before the private equity firm literally sold the land out from under it. At a national level, with nearly 8,000 healthcare institutions owned by private equity, these costs add up. Indeed, any gains toward reining in spiraling healthcare costs through the Affordable Care Act provisions and reforms to Medicare and Medicaid have been dwarfed by this constant extraction.

The losses to hospitals and communities are not only financial. A 2021 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that private equity ownership of nursing homes both upped their Medicare billings and increased patient mortality by 10 percent—translating to over 20,000 lives lost across the 12-year period they studied. Similarly, private equity-owned dental care organizations have routinely been accused of pushing unnecessary, painful, and sometimes dangerous procedures in order to secure their investors’ profit margins.

In short, this sort of “healthcare leakage” doesn’t just increase costs. It also reduces the quality of healthcare services.

What is more, it increases economic inequality and contributes to macroeconomic instability. As research shows, inequality is bad for health. The higher the economic inequality in a country, the higher the rates of health problems, from infant mortality to mental illness and obesity. Moreover, where income inequality is most pronounced, total population morbidity and mortality rates are highest. The actions of private equity firms in the healthcare sector deepen these inequalities, moving us further from our health equity goals.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The Peril of Financialization

What is happening in the US healthcare sector is illustrative of broader economic trends. More and more resources are being used to feed wealthy asset owners, to the extent that investments in actual production and services are being whittled away, leaving many of our basic institutions and services gutted.

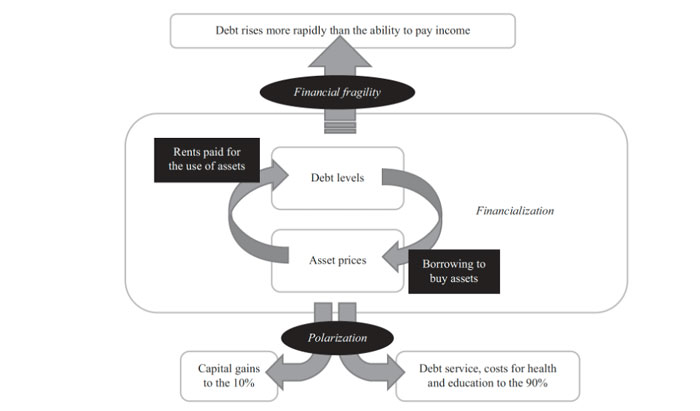

The larger trend of financialization that drives this extraction can be understood as the diversion of capital away from production, consumption, and value-added services, and toward capital gains (that is, making money from money). Such diversion helps explain why, while the media and politicians tell us that “the economy” is doing great, many Americans—and many hospitals—are struggling to stay afloat. Though US residents are putting ever more money into the US healthcare system through ever increasing Medicare and Medicaid expenditures, as well as increasing individual and private insurance payments—more money is “leaking” out, depriving healthcare of needed resources to pay good wages, invest in infrastructure, and assure quality patient care. Figure 1 provides an illustration of how this dynamic works in healthcare and across the economy.

Figure 1: Financialization in the United States: Debt and Consequences

If private equity is allowed to continue feasting on the healthcare sector unchecked, its diversion of funds from the real economy to the FIRE sector will continue to siphon off an increasing share of the already enormous resources we funnel into healthcare, making it nearly impossible to stabilize healthcare institutions and allow them to deliver high-quality care. As any doctor knows, to save the patient, sometimes you have to staunch the bleeding first.

Staunching the Bleeding

A first step to reining in private equity’s extraction from healthcare would be passing the Stop Wall Street Looting Act. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Representative Mark Pocan (D-WI) introduced this bill in the last session of Congress and are expected to reintroduce it later this year. The law would impose several new responsibilities on private equity executives, making them liable both for the debt they incur in the name of the companies they acquire and any violations of labor or environmental regulations committed as part of their management. The proposed law would also restrict dividend payments for two years after acquisition of an asset and give employee compensation higher priority in bankruptcies, thus changing incentives in an industry that takes out debt it is not obligated to repay.

Additionally, federal premerger review could be expanded to include all private equity-backed mergers in the healthcare sector. This would require reporting to and approval by the US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, increasing transparency around private equity activity in the healthcare sector and giving both federal agencies a chance to intervene before private equity companies further siphon off healthcare resources.

The Road to Healing

Equally important as curtailing private equity investments in the healthcare sector is directing new investments into healthcare, including public and community-owned healthcare institutions. Such institutions have higher rates of unionization and employment of women and people of color. As a result, their workers enjoy better working conditions and wages, while also having more say at work. The community also benefits as public and community institutions keep earnings in their local economies rather than passing profits to investors. Moreover, investing in public and community-owned institutions also helps address social determinants of health—the social factors that drive health outcomes, including economic wellbeing, access to healthy food, parks, and education, and so on—by creating good, locally rooted jobs.

Expanding access to and investing further in existing successful public institutions, like community health centers and the Veterans Health Administration, could also play an important role in supporting a healthcare system that centers healing. Broad-based ownership of these healthcare institutions is important, not only because it stems resource extraction, but also because it ensures that dollars spent on healthcare generate better health outcomes. Because they are public, institutions like community health centers and the VHA are free from the constraints of profit maximization, allowing them to deliver high-quality healthcare services and make equitable health outcomes their primary goal.

Ultimately, the goal should be to create a culture of health based on a model of health service provision that prioritizes public and community ownership.

Community health centers could be tasked to serve all Americans, bolstering the critical primary-care sector. This would increase equitable access to care and improve health outcomes and could contribute to reduced total healthcare spending. Alternatively, we could leverage existing state-run integrated primary care clinics, which offer quality care to public-sector employees in places like Montana to provide healthcare to larger populations. This could be especially important in rural areas, where for-profit healthcare clinics have been averse to making investments.

The VHA could be expanded to serve all veterans and, potentially, to reach additional populations. The VHA’s nationwide infrastructure and experience in pharmaceutical distribution, its field leadership in the use of electronic health records, and its expertise in delivering integrated, patient-centered care could be leveraged to provide quality healthcare nationwide—all without having a dollar “leak” out to shareholders.

Fostering a culture of health—and the healthcare institutions that accompany it—is not easy. One critical step, however, is to tame the private equity beast. Ultimately, the goal should be to create a model of health service provision that prioritizes public and community ownership of healthcare services in order to serve us all.

Last fall, Rebecca Givan of Rutgers University and I wrote about such a community-anchored healthcare system and outlined our vision for a regenerative economy of healthcare. In such an economy, all healthcare workers are treated with respect and enjoy broad workplace protections, regardless of their place in the traditional healthcare hierarchy, while patients and communities receive the health services they need. Instead of Wall Street, communities reap the benefits of healthcare institutions that invest in the local economy.

We believe that, by anchoring healthcare in a system of public and community ownership, it can be recalibrated to pursue its proper mission in society—namely, to provide the care and support that all people need.

Notes

- M. Hudson, “Rent-seeking and asset-price inflation: A total-returns profile of economic polarization in America,” Review of Keynesian Economics 9, no. 4 (October 2021), https://doi.org/10.4337/roke.2021.04.01.