For the past three years, NPQ has been exploring the question: Why have conditions for people of color not improved in the past 30 years, despite various DEI and racial justice efforts? 1

Our conversations with leaders of color in the field about what they need to create real social change has converged around a call to action for designing and building civic infrastructure that supports leaders of color. This expands the concept of infrastructure beyond support for nonprofit organizations, to support for leaders and the communities they serve.

The work has quickly evolved into Edge Leadership, a social change R&D platform designed primarily by and for people of color—in movements, philanthropy, nonprofits, politics, and culture—to meet, experiment, and create new forms that advance social change.

This summer, we hosted our first roundtable on this topic and found that leaders of color want to move infrastructure beyond tinkering with what is, toward a vision of how we want to be together as humans. Below are the top four themes that emerged.

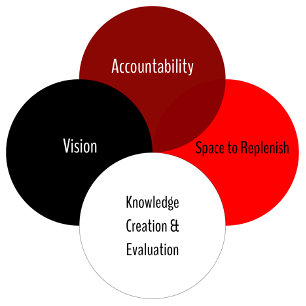

Vision

Perhaps not surprisingly, what leaders of color want most is vision.

Kristell Caballero Saucedo, Program Officer at Borealis Philanthropy says, “I think that it is important to have an image or a vision where everyone can understand what their role is and how they can thrive in this vision.”

Saucedo wants us to move away from “doing the opposite of what exists.” She explains that “the vision of what we want to live, is larger than just like the specific thing that we’re living at this moment.”

For example, this spring and summer we saw philanthropy move to fund criminal justice reform in response to months of daily massive protests across the country and beyond against anti-Black police brutality. But the problem is larger than this.

Saucedo says, “It’s larger than just things that you can give your money to one time.” Rather, “there is something that is not attached to the existing reality, but is something that we could create, or that is lifted up from the existing realities that live within our own communities, or the cultures that are being suppressed, and the stories that are being suppressed, and the value system that is being suppressed.

Author and consultant Dax-Devlon Ross agrees. “I’m concerned that the framing of a lot of the discourse right now from people in positions of authority is that this is a criminal justice issue, solely and strictly. And, so, I see a lot of our resources pouring towards justice-oriented organizations like NAACP. So, someone has defined this challenge. Who did you all talk to, to get a real sense of what is needed?”

Dr. Akilah Watkins-Butler, President and CEO of Community Progress, says, “I don’t want to pit organizations against each other, or strategies of how black folks, especially Black indigenous and Latino folks, get ahead. I’m not trying to be in conflict around that. I do think we need to have a strategy conversation around how resources get distributed.”

Kenneth Bailey is co-founder of Design Studio for Social Intervention (DS4SI), one of those rare organizations that is “on the money” in terms of what these leaders are asking for but not “on the radar” of funders. He says,

We’re trying to really use both the large social movement going on around abolition and defunding police and this COVID moment to ask larger questions about “is life working for us?”

Bailey points out that in order to build vision at this scale, we need new forms that can hold difference and complexity. He reminds us of the work of political theorists Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari when he says,

We don’t need to have one line of flight toward liberation. I feel like as we move towards the 21st century, we’re going to need to design new forms that allow people to be in them in multiple ways without being on top of each other. We have to be thinking hemispherically and globally…Where I am, is we literally just have to start to construct our world, and then try to invite people into it. That’s the best I have right now.

Marcus Walton, President and CEO of Grantmakers for Effective Organizations (GEO), says, “I often wonder how much the lack of a shared vision impacts our scattered approach to making things happen. I’m from an old school, family-run church, and for years I heard, ‘without a vision people perish, without a vision people perish, without a vision people will perish.’”

For Walton, this visioning overlaps with the cultural expression “bringing our whole selves to this work.” It “must be intentional about inviting people in to express their traditional, cultural beliefs and values through their work.” He asks, “How do we mine the wisdom from cultural practices and create something new that reflects the best of those traditions?”

Walton shares that, in his first year in his role at GEO, he’s been wanting “to ground ourselves in what’s happening right now, take a beat before we jump into action.” But he’s received pushback form people who say, “that’s not enough, we need to do more.” He understands, “We are socialized to just jump into action and do all these call-outs. The people who are new to the game don’t appreciate that visioning is the right first step.”

The work of creating liberatory visions includes an understanding of how social change occurs, its cycles and phases. This helps us not only understand the openings for transformation, but to plan ahead for the next cycle.

Anastasia Reesa Tomkin, writer and Direct Service Coordinator at Common Justice, says, “While it’s encouraging seeing these protests, I’m worried about what happens after this moment passes. People like us will pick up where the masses left off. What happens when the police unions change their game plan?”

Bailey adds, “We can start to move toward having people who are ready to encounter power in the second wave that weren’t the people who did the protest. How do we start to capture another set of people who might be able to deal with organized power in new ways?”

The work is also creative, not just strategic. It must speak to hearts and minds.

Artist Jenie Gao stresses the importance of visuals. She says, “Seventy percent of the information we receive in the world is through our eyes, so visuals are incredibly important in shaping who we believe and what we value.”

But, Gao notes, “90 percent of artists in society are white,” making the art world “one of the most unequal industries that exists.”

So, in order for visioning to include people of color as creators of visual culture, we need to, as she says, “dismantle the things keeping people out, both in terms of who has access to the art world and the stigmas attached to it.”

Darshan Khalsa, Vice President at Rivera Consulting Inc, shares that when her team recently read and discussed Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, she had a moment of realization, “Oh sh*t, this book starts in 2024. What was the future is now.”

The Parable series’ exploration of the crumbling of oppressive structures and the anarchy that ensues is resonating with many social change practitioners today.

“But,” Khalsa asks, “what do we build in its place? What are the new forms that allow us to imagine new things?”

Finally, our visioning must take into account the high risk of social change.

Khalsa says, “Knowing when to take risks is important, because our lives are at stake. When we rebuild, how do we protect ourselves? Thinking about Tulsa, what does it mean to build a thing and have white supremacy come burn it down?”

To summarize, visioning that supports leaders of color:

- Creates vision that takes into account not only who frames the challenge, but asks larger questions about how we want to live and allows us to imagine new things

- Frames the challenge in ways that equitably distributes resources

- Holds difference and complexity

- Mines the wisdom of its various cultural practices to create something new

- Understands the phases of social change

- Is not just strategic; it’s creative and highlights the arts

- Mitigates against the inherent risks involved in leading transformative social change

Accountability—Philanthropy and Government

Second on the list—unsurprisingly, given the asymmetrical power relations that undergird most social challenges—is the need for accountability from both funders and government.

Watkins-Butler gets to both the intersection between these and the point when she says: “I think that we need to push wealthy people to pay their share in taxes so we don’t have to go begging philanthropy for basic things we should have as part of being citizens.”

Cathy Garcia, Founder of Philanthropy Con Café, a platform to elevate the leadership and vision of grant makers of color, says, “The culture of philanthropy in itself has been really insidious for a long time, totally driven by proximity to whiteness and white supremacy. So, how do we hold ourselves accountable as institutions?”

She adds that over the past few months she has observed foundations set up special funds and make big public statements about the need to address injustices while Black staff inside those organizations feel the effort does not extend to them.

Garcia says,

There is an immediate pull to react and throw money, but it still doesn’t solve for internal processes that are harmful to the communities we are trying to serve and for the work that we’re trying to do.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Because as a field, philanthropy seeks to be “objective,” we forget that for many of us the communities we are serving are also our communities, and the inadequate responses of our institutions are disheartening, as an individual and as a grant maker.

This resonated with artist and consultant Wesley Days.

I worked on a two-year project around SNAP online delivery for Farragut Food that allowed for voucher housing residents in Brooklyn to be able to receive online delivery directly through SNAP benefits, the same resources that the rest of the city has through Instacart and other paid services. The Department of Agriculture piloted that project in New York first and now it’s about to expand to 22 cities, and the foundation paid for that pilot to happen.

But then when you were talking about it—the extraction process—I literally witnessed it. I watched millions of dollars be extracted through fundraisers as our work was projected online and the rich people over at Pier 60 were just given the money. And, then, I watched the process that the funder utilized in giving the money, what it required. And, so, I just felt very much like a witness to the process you just described in a very granular level.

For Days, part of the answer is reinventing civil society around decentralization of data, which is being tested via a new practice of using cryptocurrency platforms to track data.

He explains,

When I talk about decentralization, I’m not talking necessarily about ideology; I’m talking about, if resources go out, the moment they go out everybody in the ecosystem knows they’ve gone out. There’s a cryptographic hatch. It documents it the moment it goes out.

That has to become part of a new transparency that will create a continuity in knowing where the value has gone because you can go back and say, okay, you got this money, what were the results? You can hold people accountable that way.

In our system you can’t hold funders accountable because of laws that make their financial books private. But transparency forces people to think differently.

Of course, this assumes we have a value theory—a sense of where value is created, agreement that it should be amplified, and ideas as to how.

Elaine Martyn, Vice President and Managing Director of the Private Donor Group at Fidelity Charitable, says, “When we were trying to guide our donors, one of my colleagues said, ‘Isn’t there like a Feeding America version for racial injustice?’ That’s been something we’ve been thinking about. There’s a lot of confusion around, ‘how do we do this and what tools are needed to help reimagine?’”

Thus, accountability that supports leaders of color:

- Has as an ultimate goal the shifting of public dollars from philanthropy back to government, or the commons

- Extends beyond social challenges, to the destructive practices that contribute to them

- Decentralizes data so that we understand where value is created and how it is amplified

- Needs spaces, ways of thinking, and tools that help us reimagine what is possible

Knowledge Creation and Evaluation

Leaders of color also see knowledge creation and evaluation as key features of civic infrastructure.

Ross offers a timely example with how he’s come to imagine the concept of spatial justice. He describes a May 14, 2020 New York Times story based on the geotracking of people who left the city during coronavirus. It found that about five percent of the city’s population had departed as a result of the epidemic. It also looked at the parts of the city from which they left and where they went. He says, “It was this incredible, incredible indictment of the way we built cities for people who don’t need them.”

Through the relationships that are forming at Edge Leadership, Ross learned that other people are using the concept of spatial justice. He shares,

Through talking to Kenny [Bailey] I’ve discovered that there are people in North Carolina who are thinking about “spatial justice” as a way to really move social justice conversations more forward by giving them some kind of a larger umbrella to sit under that covers a lot of the different ground that we’re all trying to get at. Whether it’s health disparities or education disparities, all of them are happening in place-based settings and there is some consistency in that concept.

Ross also notes that in his conversations with people who are doing spatial justice work he’s discovered, to his surprise, “that in the last 20 or 30 years there have been dozens upon dozens of majority minority municipalities that incorporated around the country.” He wonders: How did this happen and what is being learned about how to do it?

He thinks philanthropy has a role to play in advancing spatial justice.

It’s not just in the funding of more organizational work, which is incredibly important, but what are the new ideas around this concept of how we are going to live? How are we going to push back and build a new constituency to think about, not just public investment in urban design, but how we reimagine who is involved and what the goals of urban design and development are?

Blocking access to knowledge creation is referred to as epistemological violence—the silencing of the voices of marginalized groups. Indian post-colonial theorist Gayatri Spivak introduces the concept in her classic essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” where she extends French philosopher Michel Foucault’s triad of knowledge/power/social control to explore the flip side—how marginalized groups are denied this.

Being excluded from the creation of social meaning makes it difficult for people to understand significant portions of their social experience. It is central to both the processes of normalizing white experiences as universal and othering. Epistemic violence feeds material violence because it determines what is valued and what is not, and where resources are directed.

And, so, having a sense of what we value and then designing systems that amplify that, with feedback loops that are transparent, is core to a viable civic infrastructure that supports leaders of color.

This is what Jara Dean-Coffey, Founder and Director of the Equitable Evaluation Initiative, wants to contribute to though her evaluation work. She says,

What I’m really thinking about are the ways in which our understanding of knowledge and evidence, which are grounded in patriarchy, capitalism, and white supremacy, contribute to the collective ignorance that we hold as the United States of America. So, what we believe to be true reinforces a belief system of what is value and who is valued. I desperately want to change that, and I realize in doing that a lot of Black and brown folks do not engage in knowledge generation in a way which shifts the paradigm.

A big part of the challenge is that philanthropy is the main customer for evaluation. She adds,

Philanthropy has a tremendous amount of influence on what we believe to be true, and evaluation pretends that it’s neutral. So, we just share what we see, but I see what I see because of who I am, and I give you what you want because of who paid me. So, I’m trying to make clear those paradigms and those norms so that people can own it and hopefully change and challenge it.

Dean-Coffey observes that there are not many people of color in the evaluation field. She thinks much of this is due to the history of data being used against people of color. But, she warns, “as long as we don’t touch it, it means someone else is controlling it. So I’m also trying to figure out how to break that mindset so that we’re all in the knowledge generation game and we’re not deferring to someone else who is going to continue to tell a story about us that just isn’t true.”

Clare Nolan, Co-founder of Engage R+D, adds, “I work in the space of evaluation, learning, and strategy, and one of the things we’ve been talking about is how to transform the practice of evaluation and learning so it is not a tool for reinforcing white supremacy but for equity, justice, liberation, and healing. In order to do that, we need to take care of ourselves as whole people and be in connection and alignment with grassroots organizations and people doing progressive work. We are in practice around that, we’re not living that, but it is our aspiration.”

So, access to knowledge creation and evaluation is key to supporting leaders of color. This includes:

- Strategies organized by powerful, higher-level concepts—which allow for coherence—and resourced

- Access to knowledge creation that disrupts othering and its concomitant material deprivations

- Evaluation that seeks to define, identify, and amplify value

- Philanthropy that displaces itself as the main customer by supporting evaluation that serves communities

- People of color taking a lead in evaluation, and being supported in that

Space to Replenish

Finally, leaders of color seek a place to be human and replenish, as our work is particularly challenging.

Watkins-Butler shares that she joined this roundtable because she was “needing just really good space to just be human.” The last few months have been challenging for her as she finds herself “grieving where we are as a country.”

Before she can make alliances and do multicultural work, Watkins-Butler needs space to “imagine what it means to be a Black person living in a society where there’s love and justice.”

This resonates with Saucedo, who points out that white supremacy shapes relationships between people of color. “There is no trust. There’s nothing that can help us build a relationship if we are not really having conversations that are needed to be had about why there’s no trust.”

For Darnell Adams, Co-founder of Firebrand Cooperative, infrastructure that supports leaders of color is not just an intellectual exercise; it’s a “constant coming together of head, heart, spirit.”

Reflecting on the whole conversation, consultant and policy professor Dr. Nicholas Harvey says, “What I’m hearing leaders of color saying is that they need the freedom to risk.” This makes sense, as one of the key features of edge leadership is that it is risky work.

Thus, ultimately, supporting leaders of color means supporting their ability to take risks. This includes:

- Time away from the work to imagine what is possible

- Spaces to build trust with each other

- Engagement of the head, heart, and spirit

- Help mitigating risk

In closing, infrastructure is not just physical space or things, but the ability and capacity to be part of what we’re building. It is the ability to make power accountable, including ours. It is real access to resource distribution. It is interest and skill in talking across paradigms. It is multi-vocal efforts. It is alignment. It is cultural production. It is the capacity to imagine, and create, something better—and in an exponential fashion, because time is running out.

Edge Leadership began earlier this year with a series of in-person and online convenings. This article and multi-media story series features the thinking of Edge Leaders. Follow these talented, sector-crossing, forward thinking social change agents at @EdgeLeadership2020 on Instagram, via NPQ’s channels, and by joining our closed 500-seat platform experiment.

Note

- This analysis is based on the following: BoardSource’s report on leadership trends in the sector, finding that leadership of color is low and declining, in spite of this being identified as the main challenge for decades. Feedback from readers of color to NPQ. My personal experience over my 30 years in the sector. The experience of most of my friends, many of whom are leaders in the sector.