June 27, 2014; Los Angeles Times

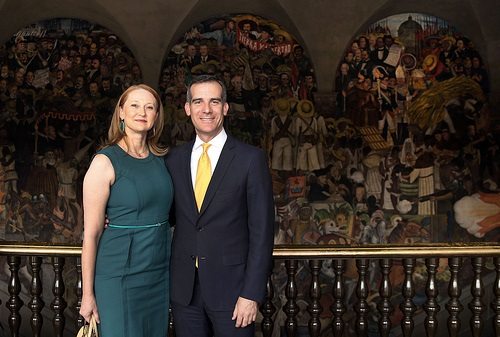

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced the creation of the Mayor’s Fund for Los Angeles to raise money for city hall efforts such as cultural tourism, summer jobs for teens, and the revitalization of the Los Angeles River. A political consultant for Eric Garcetti’s opponent in the last mayoral election, Wendy Gruel, however, called it a “slush fund” and a version of “pay-to-play.”

Garcetti’s model is similar to the Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City, which supported tree plantings, youth nutrition programs, and free Wi-Fi in 95 blocks of Harlem. Mayor Garcetti pledged “to be very careful about making sure we do everything we can to…avoid any conflicts,” but it isn’t hard to imagine, as the L.A. Times article noted, that the fund “could also provide a new venue for businesses, labor unions and special interests to curry favor” with the mayor.

Although donations to the nonprofit are in theory unlimited, Robert Stern, the former president of the Center for Governmental Studies, said that contributions of $5,000 or more must be reported to the city’s Ethics Commission.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Mayors raising money for city projects—or for nonprofit initiatives—is an increasingly common practice. Garcetti’s predecessor, Antonio Villaraigosa, did so regularly, but according to the Times, “activities also prompted complaints from neighborhood activists who asserted that donors were seeking special treatment.” That is an entirely legitimate concern, borne out in the experience of many nonprofits established by politicians. Buying face time with powerful politicians is often an invaluable investment for special interests, especially if conducted under the cover of donations to a charitable organization.

Reportedly, Garcetti’s nonprofit has already raised $2.3 million in its little more than a month of existence, including “major donations” from the Walt Disney Company, the Annenberg Foundation, and the California Endowment. Given the short time frame between the creation of the nonprofit and the appearance of the grants, it appears that the nonprofit wasn’t a surprise to some major grantmakers that were lined up quickly for their contributions.

One big issue for such politically connected funds is their need for greater transparency than typical nonprofits because of the potential dynamics between their political backers and potential special interest donors. The New York City fund’s most recent 990, posted on the fund’s city government website, does not list grantees and grant amounts, though the version on GuideStar does. Neither posted 990 discloses the donors. The most recent annual report on the fund’s webpage does not list donors, either; if the donors are listed someplace else on the fund’s website, it’s not immediately evident.

Some donors to the New York City Mayor’s fund can be uncovered through disclosures on their own 990s, including the JPMorgan Chase Foundation, the Bank of America Charitable Foundation, Deutsche Bank Americas Foundation, and the Citi Foundation, though by far the most frequent contributor to the Mayor’s fund has been the New York Community Trust, the nation’s largest community foundation.

For funds like the New York and Los Angeles entities, full disclosure of donors is really important for their impact on the democratic process. But some critics might also suggest that such funds compete for scarce donations with nonprofits themselves, which don’t have the emissaries of Michael Bloomberg or Eric Garcetti soliciting big money from foundations and individual donors.—Rick Cohen