March 31, 2019; New York Review of Books

In its latest issue, the New York Review of Books features a defense of the public library by Sue Halpern. As NPQ has regularly noted, the demise of the library has been regularly predicted, and yet its importance has instead increased. Those expecting to see decline focused on the rise of electronic alternatives to books. Of course, libraries have become repositories of electronic materials as well. But that is not the only reason why libraries remain critical. Rather, the reason for the public library’s continuing importance is both simple and profound: It is an essential public space in a world where the existence of public space is increasingly rare.

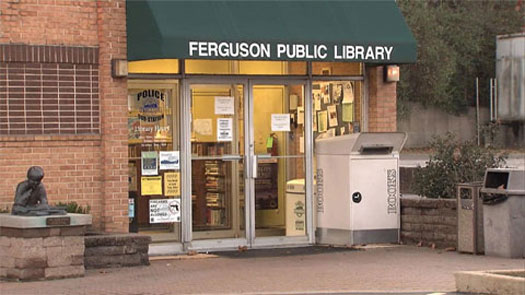

Take, for instance, Ferguson, Missouri. In the wake of the police shooting of Michael Brown, NPQ noted that it was the “library that, during the 100-plus consecutive days of community protests that followed the shooting, stayed open.” As Constance Rush, director of advocacy at the Deaconess Foundation, would note years later, it was the library that received “the community when schools and businesses and governmental agencies closed their doors.” It was the library that served as an “anchor for democracy during that time.” It was the library, Rush added, where “many school teachers came to teach up to 200 children who were at the library” when schools had been shut down.

A year later, following the death of Freddie Gray while in police custody in Baltimore, once again, “Despite Maryland being in a state of emergency, the city’s public schools being closed, and the cancellation of several recent Orioles games, all branches of Baltimore’s public libraries [maintained] regular hours and [remained] fully staffed.”

This role of providing public space in times of crisis has become an increasingly prominent part of what libraries do. A film directed by Emilio Estevez called The Public will be released next week and centers on the story of the role of Cincinnati’s library serving as a shelter for homeless patrons during a cold front; the library featured in the film is hosting a panel about youth homeless the week the film is scheduled to come out.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Libraries have served as community hubs in many ways. Earlier this year, NPQ noted that at least 30 libraries nationally have hired social workers to better serve their communities. Libraries have partnered to promote affordable housing. In Philadelphia, some librarians have even taken on the responsibility of administering Narcan, helping patrons survive the opioid epidemic.

For her part, Halpern cites Susan Orlean’s The Library Book, published last fall, which tells the history of public libraries in Los Angeles. In that book, Orlean observes that, “The publicness of the public library is an increasingly rare commodity. It becomes harder all the time to think of places that welcome everyone and don’t charge any money for that warm embrace.”

Sociologist Eric Klinenberg, another author profiled by Halpern, who wrote Palaces for the People, advances a similar argument. Klinenberg, Halpern explains, “is interested in the ways that common spaces can repair our fractious and polarized civic life.” According to Klinenberg, “Libraries are the kinds of places where ordinary people with different backgrounds, passions, and interests can take part in a living democratic culture.”

Another work on this theme is Ex Libris, a 2017 film by documentarian Frederick Wiseman, which portrays the New York Public Library. As Halpern summarizes, Wiseman’s film shows “librarians helping students with math homework, hosting job fairs, running literacy and citizenship classes, teaching braille, and sponsoring lectures. We see people using computers, Wi-Fi hotspots, and, of course, books. They are white, black, brown, Asian, young, homeless, not-so-young, deaf, hearing, blind; they are everyone, which is the point… public libraries dismantle the walls between us.”

Back in 1982, the board of the Public Library Association in 1982 issued a statement called The Public Library: Democracy’s Resource. In that statement, the group foresaw that the “forms in which ideas and information are stored change and will continue to change.” The board noted, however, that “the challenge of making the widest possible range of information accessible to all remains constant… Public libraries continue to be of enduring importance to the maintenance of our free democratic society. There is no comparable institution in American life.”

Libraries, of course, require taxpayer funding, but the cost is low. For example, Halpern reports that the per capita “library tax” for the Los Angeles County library system is a modest $32.77 per capita.—Steve Dubb