February 22, 2015; WBNC-TV (New York, NY)

As any reader of NPQ knows, social progress is often advanced by a combination of a variety of tactics, including the bringing of suits that seek to alter policy and/or punish a system for its abrogation of duty. In part, it is the exposure of facts to the public that spurs action by legislators or other elected officials, and sometimes that is augmented by a direct order by the court. Such suits can progress extremely slowly, however, and be enormously costly for all involved. What will happen if this process is bypassed?

New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer is aggressively looking to settle some high-profile civil rights cases where the city is the defendant, even before suits are filed. Most agree that this can save enormous amounts of money and time and spare people the anguish that comes with extended litigation, but will it be at all effective in sparking changes in policy?

Back in January, three half-brothers who were wrongfully convicted of murder and spent a combined 60 years in prison before being released received a $17 million settlement. A settlement of $2.25 million was made to the family of Jerome Murdough, a former marine with mental illness who died in an overheated cell in Rikers Island jail cell.

While the comptroller gets 30,000 claims a year, any of which he can evaluate and settle before a suit is filed, it is only recently that the process has been used on high-profile civil rights cases, starting with a $6.4 million award in February 2014 to David Ranta, who had been wrongfully convicted in the killing of a rabbi and was in prison for 23 years before being exonerated.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

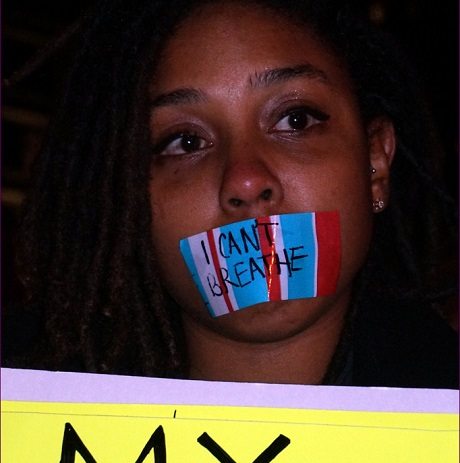

This report indicated that this may be the wave of the future under Stringer—possibly to include the case of Eric Garner, whose death at the hands of police was the source of the “I Can’t Breathe” chant of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Stringer has been quoted as saying that the city’s spending on settlements and suites increased last fiscal year ending in June by $208 million to total $732 million.

Some legal experts worry that though the practice will ease the burden on the family or individuals who have been hurt, it may also result in the details of the cases not being revealed publically. Nor do such settled cases require an admission of wrongdoing by the city or a change in policy. But James Cohen, a Fordham University law professor, says most cases do not result in a change of law.

Stringer says he wants to reduce the portion of the NYC budget devoted to settlements and that handling things this way will save money for other social needs. In contrast to the scenarios above is the story of the five teenagers wrongly convicted in the 1989 rape of a jogger in Central Park, a case that took a decade and untold amounts of money to bring and fight before it was finally settled for $41 million.

“If you settle it, you move it all behind you, and so can the victims, the families of those harmed by the underlying misdeed,” said Jill Gross, a Pace University law professor and expert in mediation and arbitration.

Jonathan Moore, attorney for the Garner family, said they have been meeting with the comptroller’s office, but Garner’s relatives have said they want to push for a change in police policy in any strategy they take—and such a thing, purportedly, would not be included in this kind of settlement.—Ruth McCambridge