Bourj el-Barajneh refugee camp, Image Credit: Al Jazeera English

At the Global Philanthropy Forum (#GPF2015) that is being covered by NPQ’s Cohen Report this week, the United Nations’ High Commissioner for Refugees, former Portuguese Prime Minister António Guterres, reminded the audience of a fact of which many NPQ readers are presumably aware: There are now 50 million refugees in the world today who have been displaced by war and conflict, the largest number of refugees since the end of World War II.

The actual number, as reported in June of 2014, was 51.2 million people at the end of 2013 who had been forcibly removed from their homes and communities, an increase of more than six million over the 2012 number. The components of the 51.2 million include 16.7 cross-border refugees (including 5 million Palestinian refugees), 33.3 million internally displaced persons, and 1.2 million asylum-seekers.

Guterres said that the number of people becoming refugees in 2015 was around 70,000 a day, if we heard him correctly. Sadly, it seems to be possible, as the agency reported that 32,200 people on average had been forced to leave their homes due to conflict and persecution every day in 2013, up from 23,400 in 2012 and 14,200 in 2011.

Perhaps Guterres said 70,000 for its shock effect, but the rate of increase in the previous years makes it sound entirely plausible, and if the mathematical progression by year is difficult to accept, the past year’s crises in Iraq and Syria with the advances of ISIS and now with the collapse of any kind of social order in Yemen provide supplementary evidence of Guterres’s figure.

The number 70,000 has additional meaning in the world of refugees. Seventy thousand is the total number of refugees that President Obama authorized this nation to accept in Fiscal Year 2015, with the following regional breakdown: 33,000 from the Near East and South Asia (who uses the term “Near East” anymore?), 13,000 from East Asia, 4,000 from Latin America and the Caribbean, 1,000 from Europe and Central Asia, and 17,000 from Africa—plus 2,000 as an “unallocated reserve.”

By Guterres’s numbers, that’s one day’s worth of newly minted refugees, although the regional allocation in the president’s executive order may not necessarily reflect where an average day’s worth of refugees are coming from—despite right-wing hysteria that the president had authorized all 70,000 refugee slots for refugees from Muslim countries.

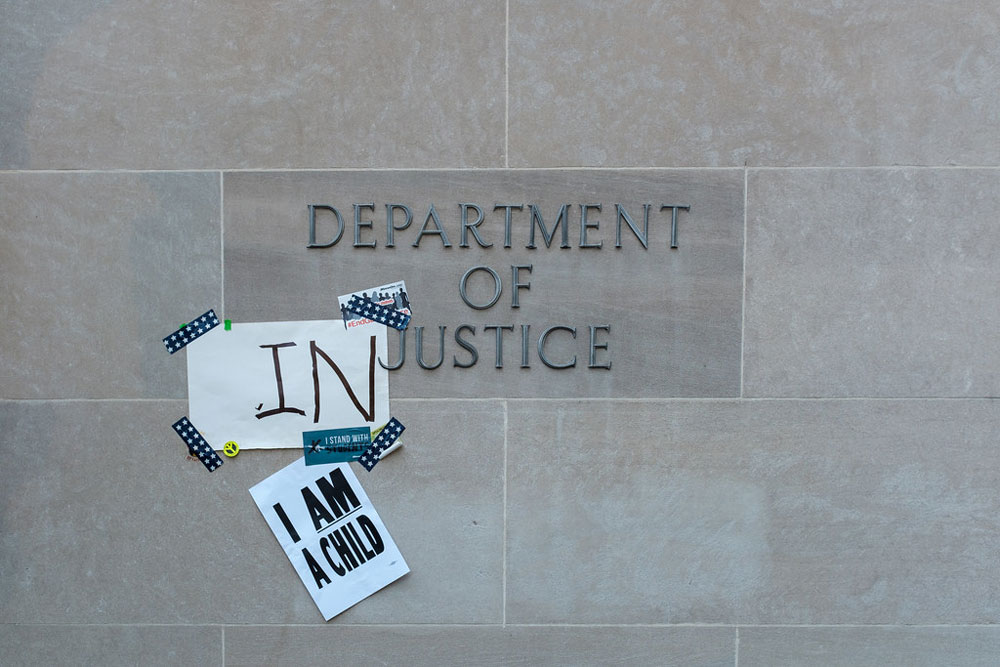

Last year, 70,000 had yet another meaning in refugee terms. It was the estimated number of unaccompanied minors expected to be apprehended by the U.S. Border Patrol after those children had made their death-defying treks to the U.S. in order to avoid violence in their home countries of Honduras, Guatemala, and elsewhere. Today, the horrors getting press attention for the moment are faced by the refugees from Africa traveling in dangerous, overcrowded boats, escaping from chaos in Libya, the Central African Republic, Nigeria, Somalia, Eritrea, and who knows how many other countries in an attempt to reach Europe.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

{loadmodule mod_banners,Ads for Advertisers 3}

The human toll of these trips across the Mediterranean is shocking. Just this past weekend, some 900 refugees died off the Libyan coast. The death toll for the year has reached 1,750, with 11,000 migrants rescued in the Mediterranean during the first 17 days of April, according to Jim Yardley writing for the New York Times. Europe’s response, now being sharply rebuked by political leaders and humanitarian aid organizations, has until this point been characterized by apathy. “How many more people will have to drown until we finally act in Europe?” Martin Schulz, the president of the European Parliament, said in a written statement. “How many times more do we want to express our dismay, only to then move on to our daily routine?”

There are humanitarian aid NGOs responding to the crisis of the Mediterranean boat people, but this is an example of what Olara Otunnu of the Uganda People’s Congress said at the #GPF2015 panel with Guterres—that an “architecture of collaboration” among NGOs and state actors is needed for effective responses to these ever-deepening problems. Like the response to refugees along the Texas-Mexico border, humanitarian assistance is needed, but the long-term solution should be one of how to accommodate and resettle the streams of refugees. Apathy is an answer that only leads to children being killed on their way to the U.S. on the Mexican Death Train, the freight trains children ride to the U.S., or the boats like the one that capsized between Libya and the Italian island of Lampedusa on April 18th.

NGOs have to focus on the politics of the issue as well as the response to the humanitarian needs involved. One way is the course recommended by Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who advised his European counterparts to simply turn the boats away. “The only way you can stop the deaths is to stop the people smuggling trade. The only way you can stop the deaths is, in fact, to stop the boats,” Abbott said, reflecting on Australia’s own experience with refugees on boats heading to Australia from Southeast Asia. “That’s why it is so urgent that the countries of Europe adopt very strong policies that will end the people-smuggling trade across the Mediterranean.”

But desperate people are going to flee and take their chances. The UN special rapporteur for the rights of migrants, François Crépeau, says that Europe’s inaction, not just in response to the people on the boats, but to the conditions that motivating people to risk their lives on the Mediterranean, has to be overcome. Crépeau, a law professor at Montreal’s McGill University, told the Guardian that Europe’s failure to act on Syria had created a “market for smugglers,” who are behind the boat incidents. He called for the West to plan to resettle one million Syrians over the next five years, which would be around 14,000 Syrian refugees a year for the U.K., less than 9,000 a year for Canada, and less than 5,000 a year for Australia—contradicting PM Abbott’s position on the issue. While Syria may be the major engine of refugees at the moment, there is no question that other conflict areas will generate more in the coming months and years, notably Yemen.

For all of the developed countries willingness to provide aid, they have been less open to welcoming refugees to their shores. According to the Guardian, the Cameron government has approved the resettlement of only 143 Syrian refugees, and even that tiny number was denounced by the UK Independence Party (UKIP), Britain’s counterpart to the right wing of the Republicans here.

In the alternative, by closing off legal opportunities for refugees to emigrate and resettle, the West is inadvertently sustaining a market for smugglers to take the refugees’ money and allow them to risk death at sea only to be turned back frequently by the national authorities in Italy, Greece, and other countries bordering the Mediterranean. “Peace is seriously in deficit,” Guterres said last year on World Refugee Day. Unfortunately, refugees are in abundance, and the challenge for NGOs, governments, and international bodies gets worse by the day.—Rick Cohen