If there’s one thing that’s thick on the ground this week in Flint, Michigan, it’s apologies. First, Governor Rick Snyder apologized as part of his State of the State speech on Tuesday for the catastrophic contaminated water situation that President Obama declared a state of emergency on January 16th. “I’m sorry, and I will fix it,” Snyder said. “Government failed you—federal, state, and local leaders—by breaking the trust you placed in us.” Then, CNN’s Jake Tapper, as something of a stand-in for the media as a whole, apologized to Flint’s mayor of two months, Karen Weaver, for not giving this story the coverage it deserved over the nearly two years since the City of Flint’s water supply was first diverted from the Lake Huron water filtered by Detroit’s water and sewerage department to the highly corrosive Flint River, which has been tainted by decades of factory runoff and subjected to a disinfectant known to cause cancer. And just yesterday, the Environmental Protection Agency administrator who oversees Michigan, Susan Hedman, delivered an apology of sorts by tendering her resignation effective February 1st. Agency head Gina McCarthy accepted her resignation, and furthermore said the EPA would begin an independent investigation, as the Michigan efforts showed “inadequate transparency and accountability.” Regrets, they’ve had a few.

As Mayor Weaver observed in her interview with Tapper, it’s hard to put a monetary value on the damage done to the infrastructure, health, and future of Flint, although she was certain that the $28 million pledged by Governor Snyder wasn’t enough to cover it. Meanwhile, there is a GoFundMe page up for the team of scientists and students operating out of Virginia Tech who, seeing that the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) was acting in a manner they characterized as “full of mistakes and deception,” pulled together a group to conduct the long-distance, independent sampling of Flint’s water that broke this story in a major way and forced the government, the media, and the world to pay attention.

According to its website, the group going by the name FlintWaterStudy was formed on August 4, 2015, in response to alleged statements from members of MDEQ that the report from an EPA agent assigned to the Michigan region on corrosion control in Flint would never see the light of day. Subsequently, 25 volunteers—4 undergrads, 11 graduate students, 7 post-docs and three faculty members—united “to help resolve scientific uncertainties associated with drinking water issues being reported in the City of Flint, Michigan.” They defined their mission as follows:

- To support citizen scientists concerned about public health, by empowering Flint residents and stakeholders with independent information about their tap water;

- To study impacts of water age and current water quality on Flint’s water distribution systems as well as issues of elevated lead and opportunistic pathogens in premise plumbing (OPPPs),

- To summarize findings from aand b to inform decision making and policy considerations, if necessary, on the part of both citizens and government agencies in the city,

- To develop a comprehensive online repository(this website) as data and information become available.

While local groups like WaterYouFightingFor and the Michigan ACLU (among others) helped Flint citizens collect water samples, FlintWaterStudy volunteered their time, resources, and expertise to analyze the samples, subjecting them to the techniques mandated under the EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule (LCR), which meant analyzing samples on an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectroscopy (ICP-MS) and reporting the 90th percentile value of lead concentrations. In the end, out of 300 sample kits sent to Flint, 254 came back—an 84.5 percent response rate—and the data confirmed what residents of the city had been saying for more than a year by that time: Flint’s water had a very serious lead problem.

There’s no level of lead in water that’s considered “safe,” but the EPA considers 5 parts per billion (ppb) of lead the level where there’s cause for concern. Forty percent of the Flint samples were at that level or higher on first draw. At 15 ppb, you start getting advised to make changes, like updating pipes and reducing corrosive elements. In Flint, the 90th percentile showed 25 ppb of lead. (The 90th percentile means that 10 percent showed a lead level above that ratio; some samples tested in the hundreds or even thousands of parts per billon.)

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

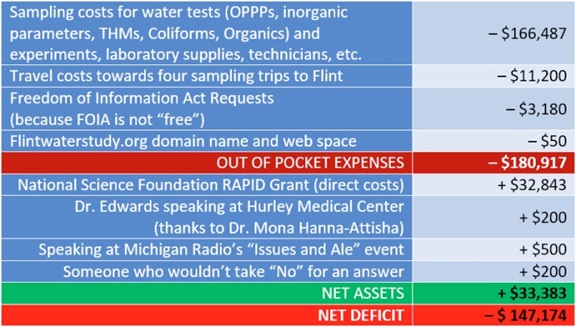

To avoid the appearance of a conflict of interest, and to remain “apolitical and fair,” FlintWaterStudy avoided most gestures of financial aid, relying on the discretionary research and personal funds of Prof. Marc Edwards, one of the group’s members. However, now that most of their work in Flint is complete, and “Flint’s kids are finally on their way to being protected and decisive actions are underway to ameliorate the harm that was done,” the team that put crowdsourced water sampling to work is now seeking to recover some of its expenses through a crowdfunded campaign at GoFundMe. Here’s their rough estimate of what their “three person-years of labor” have cost:

However, even without recouping any money, FlintWaterStudy counts its work as “priceless.” As author and team member Siddhartha Roy writes on the site’s fundraiser page, “As environmental engineers…we defended the truth and Flint residents with sound science.”

As a demonstration of the power of volunteer effort, the effect of crowdsourced action combined with nonprofit organizations coordinating locally, and the ability for science to triumph over groups lacking in transparency and accountability, the FlintWaterStudy group carries the standard for the values we prize here at NPQ. The group continues to provide updates on its website and via a Facebook group. You can see a student-made documentary on the group’s effort here, and the fundraising campaign (currently just over $6000 after eleven days) at is detailed in greater depth at flintwaterstudy.org.