This article is from the Spring 2015 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Inequality’s Tipping Point & the Pivotal Role of Nonprofits.”

Inequality may be the idea du jour, but culture is the reality that confounds. Whether we are able to make progress on inequality will depend to a great extent on the degree to which policy leaders recognize the duality of social issues. Like the two sides of a coin, the ability of social analysis to affect the world is always constrained by the perceptions that people bring to that reality. If we are to win ground toward a more equitable society, policy leaders must come up with solutions to both sides of the problem: science-based policy solutions that reduce and prevent inequity, and science-based communications solutions that address the deeply held, foundational but implicit patterns of reasoning—what anthropologists call “cultural models”—that people use to think about economic mobility. As funders and think tanks gear up to prioritize inequality as a key issue for our time, it will be imperative that we come up not only with policy solutions but with narrative solutions as well.

What Is Culture, and Why Does It Matter?

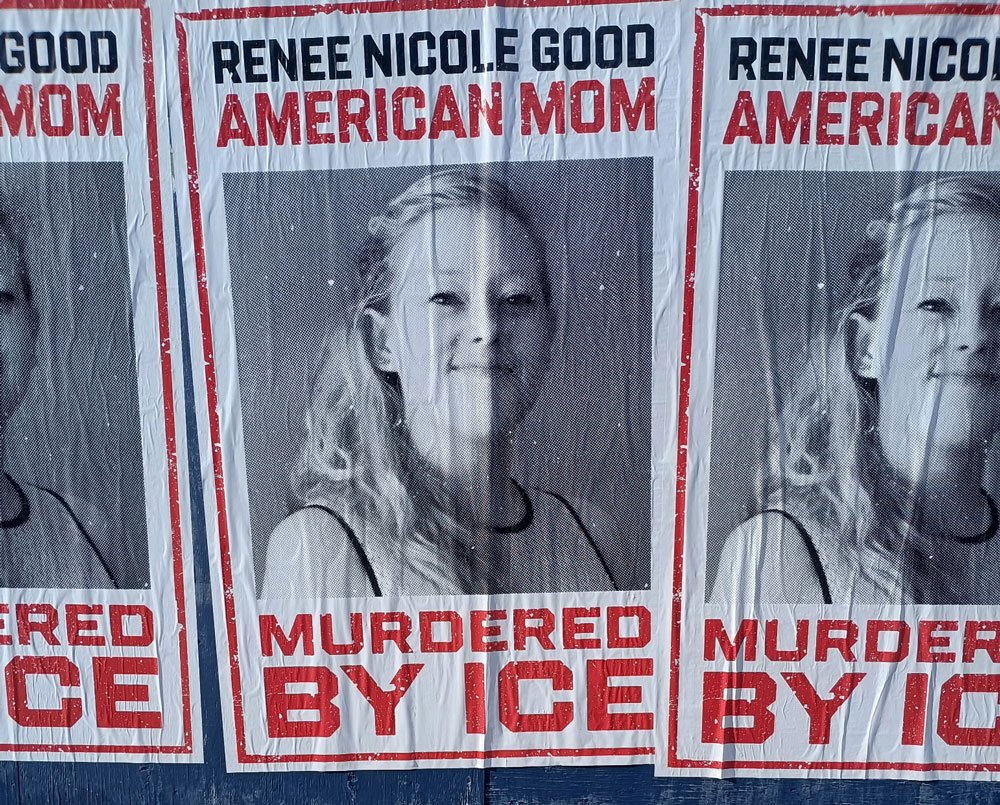

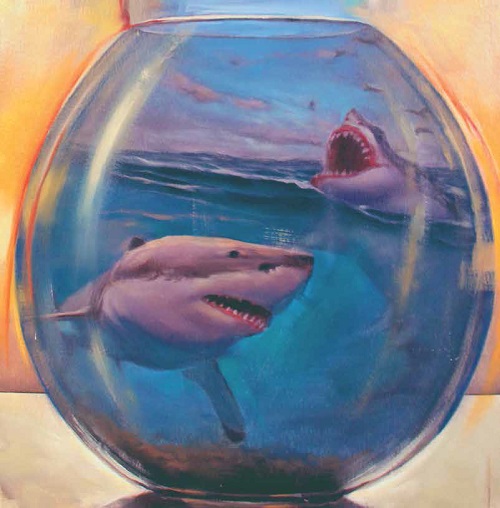

In 2014, Merriam-Webster, Inc., announced that “culture” was the word of the year, based on the number of searches. More than anything, this may represent a testimonial to Americans’ confusion over culture. What exactly is it? How does it affect us? An iconic New Yorker cartoon depicts this dilemma in two related frames: in the first, a goldfish swims in a bowl with a thought bubble overhead that says, “What water?” In the second, a man dressed in a business suit steps off a sidewalk corner in Manhattan surrounded by signs and marquee texts; his thought bubble reads, “What culture?” That’s the challenge with culture: we must try hard to see it even as we are in it and it in us. We are steeped in culture like tea bags in hot water—infused with it to such a degree that it is virtually invisible.

But culture is not an arcane concept; rather, it is a pervasive reality. This is because culture is our default setting, the locus of explanations we reach for first to make sense of our world. Our opinions of everything, from the good society to the evil empire, are shaped by our culture’s norms and stories. Scholars define cultural models as “presupposed, taken-for-granted models of the world that are widely shared (although not necessarily to the exclusion of other, alternative models) by the members of a society and that play an enormous role in their understanding of that world and their behavior in it.”1 Studying cultural models allows us to understand the context in which information is evaluated—the stories and ideas that will stick to our communications and serve to interpret it. Membership in a given cultural group is defined and facilitated by possession and use of these shared meaning structures, such that what is taken for granted is taken for granted by all those sharing the model in a way that allows for fluid and seamless interaction. As Roy D’Andrade explains, “everybody in the group knows…and everybody knows that everyone else knows…and everybody knows that everyone knows that everyone knows.” 2

Understanding the cultural models associated with any given issue allows communicators to view the meaning-making process more completely, identifying the deep narratives that people will use to understand new information. This more complete view of how people think about social issues prompts us to replace the narrow, outdated notion of humans as “rational agents or actors” who are “internally consistent,”3 “rational, selfish, and [whose] tastes do not change”4 with a more expansive and informed understanding of the mind and how it actually constructs meaning from associations, bits of stories, stored memories, and near-fit hypotheses about how the world works5—the source of which is the culture we are a part of. As Walter Lippmann observed at the dawn of the confluence of psychology and political theory, “For the most part, we do not first see, and then define, we define first and then see. In the great blooming, buzzing confusion of the outer world we pick out what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture.”6

The Culture of Inequality in the United States

What does the culture of inequality look like in the United States, and how might it be expected to shape the discourse as people consider the causes and impacts of, and the solutions to, rising income inequality in our country? In this article, we attempt to answer that question by identifying the cultural models that are consistently evident across FrameWorks’ issue-specific work and seem likely to adhere to income inequality as well. We are interested in the extent to which all the issues on which we work—children and family, government, race, environment, rural issues, food systems, and so on—reveal evidence of cultural models that are likely to be used by ordinary Americans as they grapple with the idea of inequality.

To dramatize the challenge that communicators will face, we contrast the social analysis with the cultural models that are most likely to be evoked. Drawing from a wide range of prolific communicators on inequality, we put forward an argument and then describe the cultural model most likely to be used to make sense of that assertion. In each case, we offer examples from our research across issues that give testimony to the depth and endurance of these patterns in American thinking. The cultural models we identify here are drawn from a database of over 150,000 informants, many of whom have at one time or another offered ideas and opinions about how wealth works in American society.

We have chosen examples of the expert social analysis of income inequality not because they are deficient in any way but because they represent to us a prototype of an expert, untranslated story—i.e., the gist of the social analysis that needs to be communicated. We are attempting to demonstrate that the expert story requires an analogue—a translated story—that is faithful to the social analysis but at the same time steers clear of the “pictures in people’s heads”7 that impede translation, and offers new ways of thinking about thinking.8

Ephemeral Opinions, Deep Cultural Models

If we are to believe the media, pollsters, and political parties, America is poised for a renaissance of populism: “Economic Mobility a Watchword for 2016,” says the front page of the Washington Post.9 “Big Labor Backs New Wealth Redistribution Plan,” says another headline.10 “Should Republicans Ignore Income Inequality?” asks James Pethokoukis, writing in the National Review (answer: no).11 “Democrats to propose major shift in tax burden,” announces another Washington Post article.12 “You talk to any pollster, on the Democratic side or the Republican side, they’re in complete agreement on the idea that there has to be an economic populist message,” advises Matthew Dowd, a former top strategist for President George W. Bush.13 President Obama has called populism (“economic mobility”) “the defining challenge of our time.”14

But wealth is hardly a new concept. As Thomas Piketty acknowledges in the introduction to Capital in the Twenty-First Century, “it would be a mistake to underestimate the importance of the intuitive knowledge that everyone acquires about contemporary wealth and income levels, even in the absence of any theoretical framework or statistical analysis. Film and literature, nineteenth-century novels especially, are full of detailed information about the relative wealth and living standards of different social groups, and especially about the deep structure of inequality, the way it is justified, and its impact on individual lives.”15

We can expect to find that Americans have much to say (and think) about inequality more generally, and about its various entailments: who gets ahead and how they do it, who fails and why, and why those successes and failures matter for the rest of us—as indeed they do.

To date, public thinking about inequality and wealth has been crudely characterized as an “us versus them” dilemma, or a peculiar variant of class warfare.16 Should Democrats distance themselves from Wall Street? Should Republicans offer success stories of people who have beat the odds and joined the upper echelons? These narrow diagnoses of what ails American thinking yield recommendations that have little potential to address the underlying causes of the public’s inability to fully grasp the causes and implications of income inequality. At best, these recommendations are distractions; at worst, they play into and reinforce the deep-seated belief systems that people draw upon to think about wealth accumulation. It is only by understanding these deeper strains in American thinking that experts can begin to fashion a better explanatory strategy for getting the public to see what they see.

Preflighting the Confusion over Inequality: Fatalism, Individualism, Little-Picture Thinking, and Small Solutions

Fatalism

We begin with a core proposition from Jared Bernstein and Ben Spielberg’s excellent précis on inequality: Inequality has risen sharply since the late 1970s.17 Many other explanations of inequality begin with this assertion, which seems such an obvious starting point that it is rarely questioned. “Multiple studies have revealed the growing chasm between the wealthy and everyone else,” said Matt Gardner, executive director of the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, on the release of a fifty-state analysis of state tax systems.18 But, as cultural models theory suggests, a fact without context and explanation begs the question, Why? And, without more to go on, people fall back on their “priors.”

The cultural model likely to be evoked from Gardner’s statement is fatalism. People bring this tacit perception to bear in understanding a wide range of social issues on which FrameWorks has done extensive research—from education to race to taxes to health. Whether talking about the demise of community spirit or the morals of adolescents, Americans exhibit nostalgia for a past that is collectively understood to have been better. This sense of loss dampens people’s engagement and willingness to look forward for solutions. There is little we can do to solve these issues, they reason—and therefore little reason to engage. The problem is understood as so out of hand that it is beyond control or remedy.

This way of thinking about social issues hinges on a general assumption about the lack of personal agency in the face of incredible complexity and inevitability. If the public sees that the cause of the problem is natural or determined, its response is to become fatalistic about people’s ability to affect the outcomes. We can’t go back in time to eliminate fossil fuel burning, they reason, and society isn’t going to stop relying on cars. According to this perspective, poverty and crime are intractable features of the inner-city landscape, and thus part of the inevitable life experiences of those who grow up there; politicians can throw money at underresourced communities, but they are not going to get fixed, because you can’t change human nature or stop society’s inertia in the face of change. Without an understanding of the underlying cause of an issue and the step-by-step practical actions that can be taken to address it, people reason that “things are the way they are,” and that there is little that can be done to change the situation.

As one informant described the challenge of addressing racism:

I think it’s a difficult situation, and I don’t think it’s ever gonna go away. It’s been—it’s always kind of existed, I think. I don’t think there’s any—you can probably narrow the gap a bit, but I don’t think it’s ever gonna go away.19

Another informant laments the demise of Social Security, but in a way that does not contest or protest the determinism:

I don’t know enough about Social Security to delve too deep into it other than that I keep hearing that I’ll probably never be able to retire because it’ll be gone by the time I’m old, and that saddens me, because I’m paying into it every year. Every time I get a paycheck, I pay into it, and I’m sad to think I’ll never see it.20

Here are group participants discussing how the criminal-justice system works—again evidencing the existence, application, and strength of the fatalistic cultural model:

Participant 1: If you got money, you buy good lawyers, you get off.

Participant 2: Yeah, and if you’re poor you go to jail.21

When asked what determines how a child develops, another informant responds:

I want to say it’s inevitable! And there is nothing that anybody can do, or should do any differently than they’ve been doing for hundreds and thousands of years, because it just happens.22

The above quotes are typical of our informants’ responses—and given this strong sense of fatalism, what might we expect Americans to conclude in response to the assertion that inequality has risen sharply since the late 1970s? FrameWorks’ research would predict something like this: “So many things are in decline in our country—but that’s the way the world works these days. You can’t turn back the clock. You have to look out for you and yours and just try to get by. If you’ve got a little extra, give it to charity to help those less fortunate.” In sum, a fatalistic understanding of the world depresses engagement, occludes thinking about meaningful solutions, and frames small individual gestures as ineffective but, ultimately, the only available remediation.

Individualism

Now let’s look at another pillar of the social analysis of income inequality: the idea, as Bernstein writes, that “income inequality reduces opportunities, undermines the democratic process, and distributes growth unevenly.”23 Or, as the Center for American Progress’s Report of the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity puts it, “the forces of globalization and technical change have also put pressure on middle-class families, as new and lower-cost competitors enter markets and new skills become mandatory, not just optional, for the best-paying employment. These new realities clearly call for important adjustments to economic policy.”24

The cultural model likely to be evoked by this part of the social analysis is individualism. Reasoning from this deeply embedded American model leads people to conclude that outcomes (social problems) are the exclusive result of the choices that individuals make, and that it’s up to each of us to take personal action—whether that be working “harder,” purchasing the “right” goods and services, being “smarter,” and so on—to address issues that by definition we have ourselves created (and thus whose outcomes we are responsible for). Focusing attention on changing our actions—instead of on the contexts that affect and prescribe our options and decisions—makes it difficult to communicate about common processes or structural and cultural-level forces that affect outcomes. Lifestyle choices become the solution to the most pressing societal-level issues. (Too much pollution? Plant a tree.) This bootstrap mentality narrows explanations about what causes problems and how best to address them to individual decisions and essentialist thinking about who is “deserving” of help. It creates a contextual blindness and obscures the social structures that constrain social and environmental equity.

Individualist thinking puts the responsibility for problem solving on “me,” rather than on the “we” needed to build movements to address America’s biggest issues. Approaching public problems through the lens of individualism, people become resistant to policy solutions, which are seen as mandating unnecessary bans on freedom that constrain consumption and personal choice.

Given the above, it isn’t surprising that, when talking about what can be done to improve the criminal justice system in America, FrameWorks’ informants homed in on individual responsibility:

This is America, and the only thing we seem to not be able to do is take responsibility as individuals. You want something done, you’ve got to do it yourself. You want people to stop doing crime? Then everyone needs to…be educated, and understand that you need to take the responsibility.25

Likewise, in a discussion of disparities, informants rejected the premise that race inhibits opportunity:

Hopefully we can all admit that we’re in the best country in the world, so from no matter what beginnings we come from, the possibility to succeed is there, one—and two, I think…what’s the classic line? The grass is always greener. You know what? Quit looking at someone else and thinking he’s got a better chance, he’s got more than me, he’s better looking . . . she’s this, he’s that. Just, whatever you want, it’s there. You gotta go for it.26

Finally, in discussions of how environmental conditions shape outcomes, informants again reverted to individual-level explanations:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

You have to put all of it out there. The person is going to finally make their own decision in how they want to handle all of these different influences, because even though I can sit there and say the glass is half full all day, if you want to be mad because that other part is empty, that’s how you’re gonna be. It’s the individual. You have a lot to say about how you deal with different things.27

With this emphasis on individual-level explanations for social problems, how might we expect the public to hear social analysts’ assertion that inequality reduces opportunities, undermines the democratic process, and distributes growth unevenly? FrameWorks’ research suggests that the response would sound something like this: “People make their own opportunities. They have to want them and then they have to will them into being. They have to be disciplined and save and resist temptations to buy new stuff. That is the democratic process—you get to buy what you can afford and work your way up to afford better stuff. But it’s up to you. If growth is uneven, then it’s because some people worked harder than others. That’s the American way.”

Little-Picture Thinking

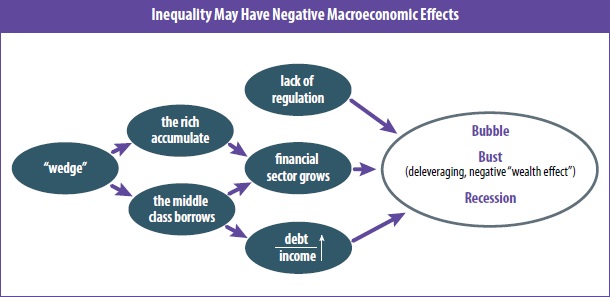

“There are serious structural challenges facing advanced economies today: the changing economic environment, rising income inequality, and the move from crisis to recovery. These are large, systemic issues that threaten inclusive prosperity.” So opens the analysis section of the report from the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity.28 Key to the social analysis is the conclusion that “inequality may even have negative macroeconomic effects” (emphasis added; and see chart on following page).29

Americans, in particular, suffer from what FrameWorks calls little-picture thinking—a kind of failure of their “sociological imaginations.”30 Without an understanding of how systems and structures work to shape individual outcomes, people default to focusing on discrete events, people, and places—little-picture thinking—which obscures the conditions and structures that undergird social and environmental issues. Thus: “Children aren’t being properly educated because teachers don’t care enough about student success,” and, “The poor are unhealthy because they don’t bother to eat right and exercise.” Little-picture thinking leads to simplistic solutions that treat the symptoms of the problem only at the most proximate level. And if individuals can’t be “fixed,” then public problems become intractable. It is easy to see how the inability to follow a chart like the one below sends people back to their go-to explanations of individualism and fatalism.31

Little-picture thinking is sharply evident in the ways people think about government budgets and taxes. Because public budgeting is a fairly abstract idea for most, people tend to rely on patterns of reasoning derived from personal experience to organize their understanding of how budgets do and should work. Informants in our research used comparisons to household budgeting, largely focused on budget balancing and living within one’s means, to think about efforts to reduce the national debt:

Well, I guess I think it [the national budget] probably works the same way the house [budget] does. I mean, so much money comes in, and then you’ve got so much money to do stuff with, and you’ve got to do the basic things, and I just think about that as…education, our roads, our healthcare, and how it all has to be spent, but spent wisely.32

The problem with this analogical thinking is that the entailments of the metaphor skew perceptions in ways that are inconsistent with basic tenets of fiscal policy. Reasoning through the “government budgets work like household budgets” lens, people find collective benefits and long-term spending hard to think clearly about. Here is an informant thinking about how he or she would create a good public budget:

I would probably start off with some kind of a spreadsheet…like a balance sheet, and looking at…what you need most…like does it have running water?…I am thinking, like, does it have electricity, running water, all this stuff. Like, those would be my priorities—just like, basic living needs.33

And because the difference between a good budget and a bad one is largely attributed to individual discipline, those who fail to live within their means are also understood to be responsible for other consequences of their actions:

People who don’t work have a higher chance of committing crimes versus people who work, because a person that works can save up enough money to buy that car, or to buy those shoes. A person who doesn’t work is not gonna have that chance to save up their money to buy this stuff, so they figure, “Okay, the fast way for me to get this money is to sell drugs on the corner,” or, “I’m going to steal money out of the register, I’m gonna steal money from the local corner store,” or, “I’m gonna rob a gas station.”34

While FrameWorks’ research on budgets and taxes is especially revealing as to how little-picture thinking gets applied and the implications of this application, this cultural model is observable on virtually any topic that relies on complex systems-level thinking. Here is an informant trying to contemplate zoning changes that would make cities more walkable and bikeable:

I think that if people aren’t walking because they don’t have a sidewalk on one street or another street, they can walk over one or two streets. That’s not an excuse. If you want to exercise, you’ll find a way to exercise.…If you want to do something, there are ways to do it and the problem is too many people find excuses not to do something.35

How is little-picture thinking likely to disrupt the information exchange invited by the diagram in the inequality chart? First, people will struggle to see a system at all. Given that, there will be a strong temptation to “fill in” individual-level understanding of causation wherever possible. The rich accumulate and the middle class borrows? This is primarily the result of differences in discipline and “values.” The relationship of income to debt? I manage my household budget, why can’t the government or other people do the same? The financial sector grows? Naturalism (that’s just the way the world works). Bubble, bust, recession? Fatalism (nothing we can do about it). Without a strong sense of causality or an underlying mechanism sufficiently familiar to displace these cultural models, Americans are likely to read into this diagram a confirmation of their old theories about how the world works.

Finally, inequality experts are eloquent in their assertions that “inequality is a problem we can combat with the right policy solutions.” 36 “We should not be fatalistic,” said Neera Tanden, president of the Center for American Progress and a member of the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity. “There are things we can do. They may be hard things. But there being hard things you can do is very different from there being nothing to do.”37

Medical anthropology offers unique insights into the degree to which the appropriateness of a therapy or prescription is judged by its coherence to what people understand about the diagnosis. 38 Put simply, if people are working under a competing definition of the problem, they are not likely to find your solution germane. Thrown back on their enduring explanations of how the world works—fatalism, individualism, little-picture thinking—most Americans are likely to find solutions to income inequality that reflect their understandings of the causes of income inequality: there are no solutions (fatalism), or the solutions lie within the willpower of individual actions (individualism), or systems are the aggregate of individual actions (little-picture thinking).

Small Solutions

In a major study of how Americans think about big-picture environmental health (including such issues as the need to protect people from air and water pollution, threats to food and safety, problems with the built environment, etc.)—the distance between the solutions experts say are essential and those the public came up with was striking. Experts focus on interventions at the population level as those having the greatest impact; FrameWorks’ informants, even when asked to think about solving large environmental health issues, opted for doing so at the level of household behaviors—i.e., small solutions. Researchers reported, “These included simple things like putting a filter on your faucet or not spreading pesticides on your lawn.”39 Likewise, when asked to consider the need to protect the intertwined systems of oceans and climate change, informants rejected the idea that changes were needed at the macro level and instead focused almost exclusively on individual acts and behavior change. These acts were characterized by sacrifice and self-discipline, matching the prognosis that greed and consumerism were at the root of environmental degradation.

It needs to start right here with you and I. Maybe you should get solar panels and maybe you shouldn’t throw out your leftovers and maybe you guys eat leftovers one night a week. And then I think if we each do little things it goes on from there. My age group is so wasteful. We just throw electronics out, which causes pollution, but the new phones come out and we get rid of the old ones. I have this fight with my husband all the time—I don’t need a new this or that. I didn’t need the 500 dollar tablet. I’m okay with the 200 dollar one.40

Indeed, public tendency to solve what it defines as individual-level problems with similarly small-level solutions is evident throughout FrameWorks’ research. Whether expressed as addressing bias in the criminal justice system by kicking out the one bad cop instead of rebuilding the policing system, or making better food choices rather than fixing the food system, or reporting neighbors who beat their kids as opposed to changing the child protection system (and supporting parents in ways that make abuse and neglect less likely to happen in the first place)—people seize on very small solutions as the primary way to address social problems. Moreover, across all these issues, people volunteer that “more information” to the individual will result in better systems-level outcomes, as this will lead to more and more individuals making better choices.41

One can easily imagine the corollary for income inequality: “There really isn’t anything you can do to make the have-nots into haves; they have to do it themselves, they have to want it. But you can alleviate their suffering by providing the most basic services that they need to survive.” And, “Fix the economy? How on earth would you do that? It’s almost like a natural system; if you monkey with it, you’re only going to make it worse.”42

Pulling and Pushing Culture

Why does it matter if these complex principles are ill understood? After all, they will soon be boiled down to slogans and human stories that will suffice to market the issue for people in the upcoming campaigns, right? And that’s the point. Without more authentically explanatory tools to contest the existing cultural models of how inequality works, these slogans and vignettes will not help people to reconsider the issue at the level required to solve it. They will be left without the tools they need to evaluate various proposals for remediation and prevention. As scholars found in studying the kinds of actions Americans tend to take on global warming, “The cultural models available to understand global warming lead to ineffective personal actions and support for ineffective policies, regardless of the level of personal commitment to environmental problems” (emphasis added).43

FrameWorks’ research across issues that touch on inequality reveals at least four major, fundamental problems with the way people are likely to hear an appeal to engage with this problem:

- It’s just the way the world (the economy) works, or fatalism.

- Individuals need to address this problem, or individualism.

- Small acts of individual effort are all we can do, or little-picture thinking.

- The best solutions are those that fit the problem, or small solutions.

Space precludes an enumeration of additional traps—such as how Americans think about fairness, for example. But the point here is that, without a firm grasp of communications analysis (i.e., understanding how people think), even the best policy experts and social scientists are unlikely to get the public to engage with one of the most important issues of our time. Moreover, public understanding requires more than avoiding negatives. If economists and others are to succeed in educating the public, they will need to understand what aspects of American thinking favor considerations of inequality and how to evoke those more productive cultural models. Framing is a “pushing and pulling art”—a constant awareness of what you have to work with in people’s mental repertoires.

This is not to overlook the fact that there are many interesting communications hypotheses in current expert discourse on inequality. The Great Gatsby curve, the birth lottery, inclusive prosperity, and so on—these are useful first drafts of a reframing strategy. The problem lies in knowing which of these work, and what they do exactly. Do they help people understand how the economy works, how systems affect individual outcomes, why the fates of the rich are connected to those of the poor, how solutions connect to causes, and who is responsible for those solutions? Or are they merely bunting on the platform of the next candidate for public office?

Public communicators have made an important stride in recent years—the notion of the 1 percent has redrawn the us-versus-them lines that have plagued discussions of income inequality for years. But even this important contribution is insufficient to overturn the fact that most Americans think the United States benefits from having a class of rich people, and more than a quarter of young people believe it’s somewhat likely that they will become rich.44 Nor does it assail the cultural models we’ve identified above (fatalism, individualism, little-picture thinking, small solutions). The 1 percent strategy leaves unaddressed fundamental issues of how the economy works, who is responsible, and who benefits (and with what consequences).

“The distribution of wealth is too important an issue to be left to economists, sociologists, historians, and philosophers. It is of interest to everyone, and that is a good thing,” writes Thomas Piketty in the opening pages of Capital in the Twenty-First Century.45 For too long, we have used social science to pioneer better solutions and interventions, while failing to bring these same methods and theories to help reformers think about thinking. If we want to make progress, we need to apply the same high standards to the communications we promote as we do to our proposed policies. And the solution is not a poll here and a focus group there but a deep and systematic evaluation of the communications tools we have available so as to match tool to task, to address the deep-seated cultural models in mind that threaten to preclude public buy-in.

And then we need “frame sponsors.” “Although humans are not irrational, they often need help to make more accurate judgments and better decisions, and in some cases policies and institutions can provide that help,” says Daniel Kahneman. 46 While expert economists are one source of information, there are those in communities who are already explaining how wealth works, and for whom and with what consequences, on a daily basis. For example, the leaders of social welfare agencies, under the umbrella of the National Human Services Assembly, are in more than 150,000 communities every day explaining why underserved youth need after-school programs, how more families came to be at the local shelter this month, and who needs work training programs and why. Without a coherent narrative that is shared across these various levels of expertise—academics, practitioners, frontline advocates, and service providers—those who favor actions on income inequality are likely to be disappointed.

• • •

The American public deserves a better story about income inequality. Its public communicators deserve better social science on how to communicate that story. If we are to transform the culture of inequality, we will need strategy that marries the social analysis to the communications analysis. For, when we squander our storytelling resources, the current cultural models predominate.

Notes

- Roy D’Andrade, “A Folk Model of the Mind,” in Cultural Models in Language and Thought, ed. Dorothy Holland and Naomi Quinn (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 112–49.

- Ibid., 113.

- Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2011), 411.

- Bruno Frey, quoted in Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, 270.

- For a complete discussion of mental processing, see Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, or Bradd Shore, Culture in Mind: Cognition, Culture, and the Problem of Meaning (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

- Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (1922; repr. New York: Free Press, 1965).

- Ibid., 4.

- For more on the difference between expert and translated stories, see Jack P. Shonkoff and Susan Nall Bales, “Science Does Not Speak for Itself: Translating Child Development Research for the Public and Its Policymakers,” Child Development 82, no. 1 (January/ February 2011): 17–32.

- Dan Balz and Philip Rucker, “Economic Mobility a Watchword for 2016,” Washington Post, January 12, 2015.

- Connor D. Wolf, “Big Labor Backs New Wealth Redistribution Plan,” Daily Caller, January 12, 2015.

- James Pethokoukis, “Should Republicans Ignore Income Inequality?,” National Review Online, January 9, 2015.

- Lori Montgomery and Paul Kane, “Democrats, in a Stark Shift in Messaging, to Make Big Tax-Break Pitch for Middle Class,” Washington Post, January 11, 2015.

- Balz and Rucker, “Economic Mobility.”

- Barack Obama, “Remarks by the President on Economic Mobility” (speech, Center for American Progress, Washington, DC, December 4, 2013).

- Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2014), 2.

- Andrew Levison, “The 2014 election produced the most serious discussion about Democrats and the white working class in many years,” Democratic Strategist, “Democratic Strategist Strategy Memo,” January 14, 2015.

- Jared Bernstein and Ben Spielberg, “Increasing Inequality: It’s Happening, It Matters, and We Can Do Something About It” (PowerPoint presentation, On the Economy: Jared Bernstein Blog, January 6, 2015).

- “New 50-State Analysis: Working Poor Families Pay Double the State Tax Rate Paid by Top 1 percent,” press release, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 13, 2015.

- Moira O’Neil, “My Race is My Community”: Peer Discourse Sessions on Racial Disparities (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2009), 11.

- FrameWorks Institute, Aging (Washington, D.C.: FrameWorks Institute, forthcoming).

- Yndia Lorick-Wilmot and Eric H. Lindland, Strengthen Communities, Educate Children, and Prevent Crime: A Communications Analysis of Peer Discourse Sessions on Public Safety and Criminal Justice Reform (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, July 2011), 21.

- Nathaniel Kendall-Taylor, Experiences Get Carried Forward: How Albertans Think About Early Childhood Development (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2010), 12.

- Bernstein and Spielberg, “Increasing Inequality.”

- Lawrence H. Summers and Ed Balls, Report of the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity (Washington, D.C.: Center for American Progress, January 2015), 25.

- Lorick-Wilmot and Lindland, Strengthen Communities, 16.

- O’Neil, “My Race is My Community”, 12.

- Nathaniel Kendall-Taylor and Chris McCollum, Determinism Leavened by Will Power: The Challenge of Closing the Gaps Between the Public and Expert Explanations of Gene-Environment Interaction (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2009), 17.

- Summers and Balls, Report of the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity, 23.

- Bernstein and Spielberg, “Increasing Inequality.”

- See C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 1959).

- The chart depicts the following, as described by Jared Bernstein: “As shown, as the ‘wedge’ between overall growth and the compensation of the typical worker grows, higher income households are expected to increase their savings. Middle class households, on the other hand, must borrow more to maintain their living standards; as they do, their debt-to-income ratios begin to rise. This leads to an expansion in the financial sector, as noted by Michael Kumhof and Romain Ranciére: ‘the bottom group’s greater reliance on debt—and the top group’s increase in wealth—generated a higher demand for financial intermediation’ during the 2000s expansion.

“In the absence of sufficient financial market oversight—itself arguably a function of the interaction of wealth concentration and money in politics—financial markets become increasingly unstable and the system eventually crashes. Borrowers aggressively deleverage while wealth effects quickly shift into reverse, leading to a contraction in overall demand and recession,” Washington Post; Post Everything; “Inequality and the economic ‘shampoo cycle’: bubble, bust, repeat…,” blog entry by Jared Bernstein, November 14, 2014. - Nathaniel Kendall-Taylor and Susan Nall Bales, Like Mars to Venus: The Separate and Sketchy Worlds of Budgets and Taxes (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2009), 22.

- Ibid., 13.

- Alexis Bunten, Nathaniel Kendall-Taylor, and Eric Lindland, Caning, Context and Class: Mapping the Gaps Between Expert and Public Understandings of Public Safety (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2011), 27.

- FrameWorks Institute, Civic Wellbeing: An Analysis of Qualitative Research Among California Residents (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2006), 13.

- Bernstein and Spielberg, “Increasing Inequality.”

- New York Times; The Upshot; “Trying to Solve the Great Wage Slowdown,” blog entry by David Leonhardt, January 15, 2015.

- See Nathaniel Kendall-Taylor, “Treatment Seeking for a Chronic Disorder: How Families in Coastal Kenya Make Epilepsy Treatment Decisions,” Human Organization 68, no. 2 (Summer 2009): 141–53; Holly F. Mathews and Carole E. Hill, “Applying Cognitive Decision Theory to the Study of Regional Patterns of Illness Treatment Choice,” American Anthropologist 92, no. 1 (March 1990): 155–69; and James M. Wilce Jr., ed., Social and Cultural Lives of Immune Systems (New York: Routledge, 2003).

- Eric H. Lindland and Nathaniel Kendall-Taylor, People, Polar Bears, and the Potato Salad: Mapping the Gaps Between Expert and Public Understandings of Environmental Health (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2011), 45.

- Andrew Volmert et al., “Just the Earth Doing Its Own Thing”: Mapping the Gaps Between Expert and Public Understandings of Oceans and Climate Change (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2013).

- Ibid., 48.

- For more on this, see Michael Baran et al., “Handed to Them on a Plate”: Mapping the Gaps Between Expert and Public Understandings of Human Services (Washington, DC: FrameWorks Institute, 2013).

- Willett M. Kempton, James S. Boster, and Jennifer A. Hartley, Environmental Values in American Culture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995).

- Frank Newport, “Americans Like Having a Rich Class, as They Did 22 Years Ago,” Gallup.com, May 11, 2012.

- Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 2.

- Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, 411.