For justice-centered leaders, there is a stubborn dichotomy between our genuine commitment to equity, inclusion, and alignment in our organizations on the one hand, and our continuing self-diagnosis of high levels of misalignment, conflict, and turnover on the other. Three years after Maurice Mitchell’s seminal piece, “Building Resilient Organizations: Toward Joy and Durable Power in a Time of Crisis,” rang the alarm of “urgent concerns about the internal workings of progressive spaces,” the current discourse suggests that the needle has not moved much.

Building Movement Project’s report, The Push and Pull: Declining Interest in Nonprofit Leadership found not only a decline in interest in executive leadership but also that those who are interested in leadership are motivated by fixing what they see as not working: “These trends suggest a ‘push’ into leadership roles to ameliorate the issues nonprofit staff have experienced, rather than a ‘pull’ into these roles on their merit.”

Even more visceral is writing by leaders themselves. In “Three Patterns Disrupting Nonprofit Culture and Sustainability,” veteran fundraising and organizational executive Sonya Shields recently wrote: “We are in a time where modern tribalism, empathy without discernment, and cancel culture are shaping nonprofit workplaces more than values. Nonprofits are using language of equity and justice while replicating dynamics that silence truth, punish leadership, fracture trust, and dehumanize people who have helped to build nonprofits for years.”

It is not for a lack of effort among justice-centered leaders. “The past five years have been the most challenging time to lead that I’ve seen in my lifetime,” Bridgespan cofounder Jeff Bradach wrote in July 2025. And even still, many justice-centered leaders are practicing shared or co-leadership models; many are sustaining virtual or hybrid workforces to promote employee wellbeing; and some are undertaking the arduous work of integrating unions. We posit that the gap between our aspirations and our operations in justice-centered nonprofits is largely due not to a lack of effort, but to the lack of a coherent theory and practice of organization design.

What Is Organization Design?

“Organization design as a concept is rather new to the social sector. We understand roles and organizational charts, but organizational charts give us very little information and tell us even less about how to work together to build collective power,” explained Julian Chender, a social sector organization design practitioner of 11A Collaborative, in an interview with NPQ.

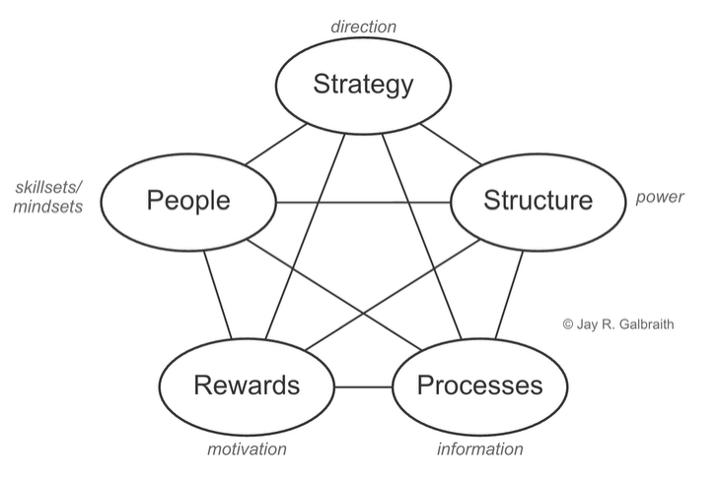

The Star™ Model, created by leading organization design theorist and practitioner Jay Galbraith, is an illustration of organization design’s core premise: For an organization to thrive, alignment is necessary among five organizational elements—its strategy, structure, processes, rewards, and talent.

Star Model™ of Organization Design

“As the layout of the Star Model™ illustrates, structure is only one facet of an organization’s design. This is important. Most design efforts invest far too much time drawing the organization chart and far too little on processes and rewards,” Galbraith wrote. Organization design theory proposes that leaders begin with organizational strategy and make intentional, integrative choices about what structures, what processes and systems, what metrics and compensation, and what skills and talents will best energize that strategy. And further, that when organizational strategy shifts over time, as it necessarily will in our volatile context, so too must structures, systems, metrics, and talent.

In their book, Leading Organization Design: How to Make Organization Design Decisions to Drive the Results You Want, Gregory Kesler and Amy Kates argued that organization design is a core leadership competency that entails “aligning the components of the organization to execute strategy and removing barriers so that members of the organization can make the right decisions and do their best work.” It is this continuous alignment of components, or its absence, that drives organizational culture. As the authors wrote, “It is impossible to change culture directly. Culture is the result of decisions made regarding structure, processes, metrics, and talent.”

Even with this very initial introduction to organization design as a discipline, we encounter powerful challenges to nonprofit norms, including:

- Nonprofit leaders typically view the five elements in the Star Model™ as separate considerations managed by distinct staff people, supported by distinct consultants, and invested in, as possible, with distinct capacity building grants.

- Nonprofit leaders typically emphasize direct work on organizational culture, holding it as a precursor of organizational alignment rather than a result of it.

- Nonprofit leaders typically do not hold processes and systems as crucial to organizational alignment in the way that organization design does.

In our view, these challenges are very important for progressive leaders to sit with. We believe that organization design offers leaders a framework in which to understand why many of their well-intentioned interventions have not produced the sustained alignment they hoped for and to reorient how they approach strengthening and aligning their organizations going forward.

We also believe that significant differences in how justice-centered leaders specifically want to lead—compared with leaders of mainstream organizations—mean that they can adapt organization design without losing the benefits of its integrative rigor. We offer guidance on the application of the Star Model™ in a justice-centered organization below.

The Star Model™: Strategy

As a discipline, organization design begins with clear organizational strategy. This is logically impossible to do if staff do not share an understanding of what strategy is and what their organization’s active strategies are. A great source of conflict in justice-centered organizations is the false assumption that shared commitment to a mission and vision will result in shared commitment to how an organization pursues that mission and vision.

In response to Mitchell’s “Building Resilient Organizations,” Rebecca Epstein and Mistinguette Smith wrote “Paving a Better Way: What’s Driving Progressive Organizations Apart and How to Win by Coming Together.” All three writers emphasize the critical role of well-socialized strategy in organizational alignment. As Epstein and Smith pointed out, “Many organizations are not clear enough—both externally and with their staff—about where they come from, who they are, what they are trying to do, and why.”

For years we have lamented strategic plans that “sit on shelves” and insisted that the days of “predict and execute” are long gone. It’s a bewildering phenomenon; we have many truisms about strategic planning but no widely shared definition of strategy itself. In “How to Transform Strategic Planning for Social Justice,” Nick Takamine describes successful justice strategy development processes like this:

Instead of prescriptive plans, they provided clarity of strategic intent: an assertion of what they aimed to achieve and by what means. They did so through a set of interconnected strategic decisions that linked a compelling purpose to a clear analysis to a coherent organizational response.

And, for a concise definition of strategy relevant to justice work, we offer this one from Malcolm Ryder of Archestra Research: “Strategy is a theory about what would generate enough influence to become a causal factor in realizing the vision.”

For strategy to function as the primary orientation of an organization’s work and design, it must express how specifically the organization will generate its influence on the people and systems it exists to affect. One of the many benefits of the organization design framework is that it gives leaders a way to reintroduce and recenter strategy for its own sake, and as the driver of a continuous set of choices that must be made to ensure the organization is relevant and viable in an indefinitely volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous operating context.

Guidance to Justice-Centered Leaders:

Choose and socialize a single definition of strategy; practice explicitly anchoring all important conversations, meetings, and decisions in your organizational strategy.

Leadership Discussion Questions:

- How have we been using the word “strategy” in our organization?

- What effects has this usage had across the staff and board?

- What definition of strategy will we select and socialize?

The Star Model™: Structure

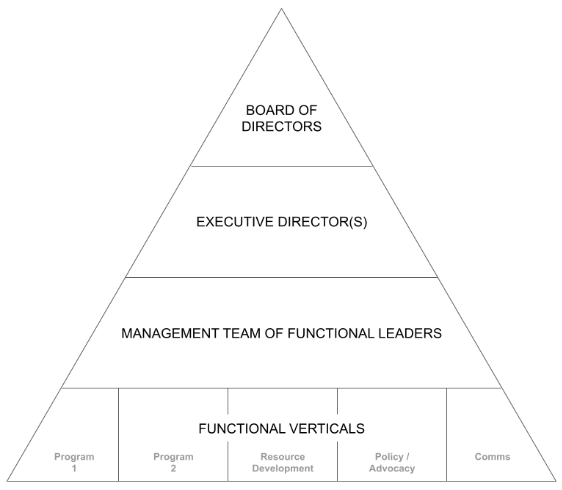

Most justice-centered nonprofits continue to operate in a functional bureaucracy. While some now have co-executive directors—and a great many have equity task forces or other types of satellite committees trying to address internal dynamics—the overarching model typically holds: a board of directors, the executive director(s), a management team of senior representatives from functional departments, and then the functional departments themselves.

A central problem for justice-committed organizations with this vertical design is that justice strategies are very often interdisciplinary, or “horizontal.” Justice-centered organizations rarely have a clean, one-to-one relationship between their strategies and their group structures.

On the contrary, people from multiple functional groups have a stake in such strategies as narrative change, power building, policy change, member leadership development, voter engagement, partnerships and coalitions, fund development, and so on. So, if strategy is to be the driver of organizational structure, as organization design theory proposes, we have to question whether a primarily vertical structure is applicable to horizontal strategies.

Moreover, the traditional nonprofit design is ill-fit for justice-centered leaders and staff because we typically want to avoid the characteristics of what Niloufar Khonsari, author of The Future is Collective, aptly calls “pyramid power.” These characteristics include: the “bottleneck effect” on decision-making; “exploitation and extraction” whereby wealth and power accrue to the very top of the structure; and “exclusion and collective disempowerment” where the organization does not benefit from the “collective wisdom, skills, and experiences of the great majority of the organization’s members or employees who are structurally disempowered.”

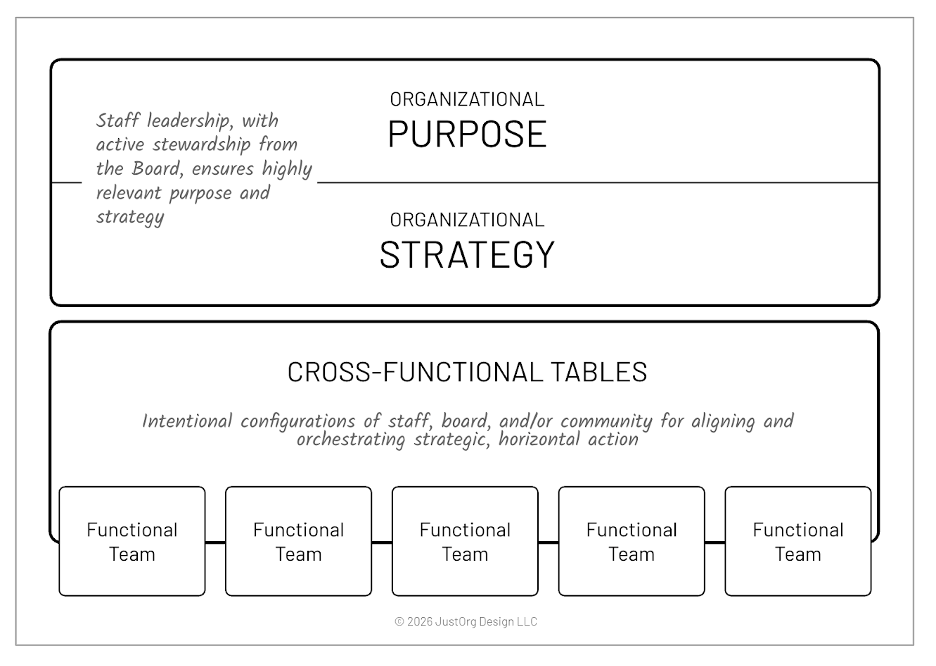

From an organization design perspective, it is not that everyone in an organization needs to be activating every strategy and part of every decision, but rather that leaders combine a centering of strategy with a strong bias for engaging “collective wisdom, skills, and experiences” to energize bodies of work as powerfully as possible. Put another way, a justice-centered nonprofit’s structure can be an explicit expression of both its current strategies and its values.

There are alternative ways to approach structure, and its graphic representation, in a justice-centered nonprofit. In the visual below, for instance, organizational purpose and strategy, stewarded by board and staff leadership, sit atop the image to emphasize that it is purpose and strategy that drive organizational structure and decision-making. Next is a layer of cross-functional tables, some of which will shift in emphasis as strategy shifts, allowing intentional configurations of staff, board, and/or community to align horizontally. And finally, functional teams drive the distinct, recurring bodies of work.

As the organization design practitioner Jules Siegel-Hawley described to NPQ, “We inherit structures as if they’re fixed, but they’re really just choices made at a moment in time. Design is an ongoing act of leadership. It is a continuous practice to decide what still serves the mission and what no longer does.”

Guidance to Justice-Centered Leaders:

Expand your thinking about structure beyond the false binary of hierarchical or flat; get creative about how you configure people to grapple with and energize organizational strategy together.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Leadership Discussion Questions:

- Do we have, for all intents and purposes, a pyramid structure? How so or how not?

- Can one see our current organizational strategies in how we are structured?

- What changes to our structure could (re)center organizational purpose and strategy as what inspires execution across our functional teams?

The Star Model™: Processes

We still have leaders and consultants in the social justice space who downplay the role of processes and systems, particularly if they involve technology. But as technology leader Afua Bruce reminded us:

Nonprofits that successfully harness the power of data and technology recognize it isn’t just an information technology (IT) concern. It’s a strategic, organization-wide transformation that requires intentional guidance to connect digital tools with mission objectives, and, when done well, can empower both staff and community.

This is even more essential for justice-centered organizations that want to preserve hybrid and virtual workplaces where we can no longer seek clarity at the proverbial water cooler. Getting people who are comfortable with systems and technology onto leadership teams and onto strategic, cross-functional tables is key to identifying and improving the processes that make work smoother and more transparent for everyone.

Decision-making processes also live in this section of the Star Model™. In justice-centered organizations concerned with how power is held, these processes can cause great consternation. Typically, there is a hyperfocus on who gets to make a given decision, but how different kinds of decisions are made and actualized over time is rarely addressed.

Indy Johar of Dark Matter Labs cautioned that we falsely “talk about decisions as if they are things—discrete, bounded objects that can be picked up, placed on a table, and examined.” When in practice, “a decision is not made once; it is continuously made, remade, and unmade as contexts change and new information arrives.” He concluded that “if we take decisions seriously as flows, a different image of governance emerges. Governance becomes less about objectifying moments and more about cultivating decision ecologies: infrastructures for alignment, dialogue, and iteration.”

Thus, structures are absolutely crucial to clearer, wiser organizational decision-making. Sending important decisions up and down the pyramid is slow and disempowering to the people doing the work and generating ideas. Moreover, the typical leadership team made up of senior functional leaders from each department is not the optimal mix of knowledge and proximity for every strategic decision.

Instead of constantly saying, “That’s an executive leadership team decision,” we should send senior leaders out into the organizational system—especially onto cross-functional tables—where they can bring their expertise, influence and be influenced, and represent executive perspectives.

Guidance to Justice-Centered Leaders:

Prioritize clear organizational processes—supported, as appropriate, by technology—that make work smoother and more transparent, allowing people to learn and adapt with intention.

Leadership Discussion Questions:

- Are we deeply committed to strong systems, including appropriate use of technology?

- Do we train people well on our critical systems and ensure they are accountable for using them optimally?

- Is our decision-making practice aligned to our values and supportive of teams getting proper guidance with minimal bottlenecking?

The Star Model™: Rewards

The rewards part of the model is a place where justice-centered leaders can and should reimagine mainstream organizational practices entirely. Compensation in justice-centered organizations should be simplified, made as transparent as possible, and decentered in favor of other types of motivational rewards in the organization’s design. Justice-centered leaders need not be complicit in myths about knowledge-work compensation, which sociologist Jake Rosenfeld noted are “widespread, often uncontested, and misleading.” The three myths are that “you can fully separate your performance from the contributions of others”; that “your job has an objective, agreed-upon definition of performance”; and that “paying for individual performance leads to positive organizational outcomes.” These myths certainly apply to justice-centered organizations where staff activate horizontal strategies across a mix of functional and cross-functional structures.

Opaque, “market-based” salaries, raises, and bonuses keep us bound to structures and ways of working that are anathema to social justice values and to the levels of collaboration and cross-functionality our strategies require. They rely on overdefinition of job descriptions and overcontainment of people’s capacities in order to rationalize pay differences, and they consume enormous amounts of administrative time without contributing to strategic clarity or agility.

We believe justice-centered leaders should reward staff with ethical compensation, excellent benefits, opportunities to learn and develop, and with an unwavering attention to the structures, systems, and talent they need around them to energize organizational strategy with joy. These nonmonetary rewards—learning and development and a well-designed organization—are powerful means for attracting and retaining talented people.

Metrics, or how an organization visibilizes its priorities and milestones, are also considered here, as they motivate and shape individual and group behaviors. Because justice strategies tend to be complex and interdisciplinary, they often do not lend themselves to quantifiable data that drive learning and adaptation. We posit that justice-centered organizations will benefit most from capturing their real-time data—key decisions made, key actions taken, formal and informal feedback received, and so forth—and building in lots of well-structured time for collective sensemaking.

Unlike dashboards that typically report on quantifiable factors predicted during a strategic planning process to be important to executives and boards, a real-time data and sensemaking approach is consistent with strategy that is alive and adaptive. It is also much more effective at building the strategic thinking capacity of people and groups because it exposes them to repeated examples of strategy in play in the real world.

As Siegel-Hawley argued, “Strategy is a rhythm. The more often teams revisit what matters most, the more naturally structure, roles, and priorities align around it.”

Guidance to Justice-Centered Leaders:

Embrace a much broader notion of employee incentives and rewards than traditional compensation models.

Leadership Discussion Questions:

- Is our compensation approach in alignment with our values and motivating people to work collaboratively to activate organizational purpose and strategy?

- Do we see our organization design role as leaders (ensuring right talent, rights systems, etc.) as a primary means of rewarding people for their contributions?

- Are we rewarding people with opportunities to learn and develop, including through regular access to strategic sensemaking about our work and impact?

The Star Model™: People

The positioning of “people” last in the Star Model™ is purposeful and perhaps the greatest challenge of organization design to nonprofit norms. As Chender told NPQ:

The social impact field broadly and the social justice field specifically are necessarily relationally focused. This tends to mean that organization structure decisions are made around people, which is unfortunately the first sin of organization design. Organizations should be built around the impact they want to have in the world, which goes back to strategy and theory of change.

Our inalienable valuing of people and relationships as justice-centered nonprofits should not include having people on staff who cannot or will not bring their full commitment to energizing organizational purpose and strategy. When we leave people to flounder in roles they should not be in, or maintain roles that current strategy does not require, the whole system and the people inside it suffer; the integrity of the design is profoundly compromised.

The relationship between people and organization design is also obviously a deeply political one for justice-centered leaders. It is very common among justice-centered leaders to quote adrienne maree brown’s work on emergent strategy in naming organizations as fractals of the systems and society we want to nurture.

This requires leaders to sit in the tension between individual needs, which vary considerably, and institutional needs, which have to cohere toward influencing social change effectively. This is an inevitable tension between individualism and collectivism. “Our whole society is rewriting the social and economic contracts that have governed our institutions for hundreds of years…It is a job. If we don’t take that job seriously as a part of what we do, we won’t need segregationists to break us apart. We will do that to ourselves,” Karla Monterroso, founder and managing partner of Brava Leaders, wrote.

Guidance to Justice-Centered Leaders:

Invite people into a collective organization design mindset; regularly articulate how the strengths and talents of the staff fit together to energize current organizational purpose and strategy.

Leadership Discussion Questions:

- Are we letting people flounder in roles that are ill-defined, a mismatch for their skills, and/or out of sync with current strategy?

- As leaders, how are we balancing the expressed needs and desires of individuals with the organization’s need to generate causal influence toward our vision?

- As leaders, do we embrace what Monterroso calls “the job” of rewriting the contracts that have governed our institutions for hundreds of years?

Leaders as Organization Designers

We have made it around the Star Model™, offering lessons from our work applying organization design in justice-centered organizations. Leaders and practitioners alike must constantly remind themselves of the reverberation that bounces among the star’s five elements (thus the arrows in Galbraith’s drawing of it).

For instance, though organization design is emphatic about the primacy of strategy, it is, of course, the people situated in structures that must develop and adapt strategy. As Kesler and Kates wrote, “Sometimes the organization needs to be designed to create new conversations that allow new strategies to emerge and be acted upon.” We see this need across the social sector right now as it metabolizes major shifts in the sociopolitical context.

What is certain is that nonprofit leaders are organization designers, and further, that they have agency over their designs. Nicole Wires of Nonprofit Democracy Network, which supports people who want to deepen democracy within organizations and movements, told NPQ, “The greatest power of this agency is that our organizational designs can be emergent, flexible, and responsive to current conditions. In building just organizations, we have the great gift to, as beloved movement ancestor Grace Lee Boggs implores, ‘transform [ourselves] to transform the world.’”