September 4, 2017; NPR

For most workers, these are not good times. Jobs may be there but, according to the Economic Policy Institute, the majority has seen no real earnings growth for decades: “Over the…34-year period between 1979 and 2013, the hourly wages of middle-wage workers (median-wage workers who earned more than half the workforce but less than the other half) were stagnant, rising just 6 percent—less than 0.2 percent per year…The wages of low-wage workers fared even worse, falling 5 percent from 1979 to 2013.” Only the highest-paid workers experienced significant salary increases.

Despite capturing the support of many hoping for change, the 2016 election and subsequent inauguration of President Trump did not bring pro-labor changes to government action or policy. Speaking to NPR, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka said that the president’s “promises in the campaign haven’t matched up with what he’s done.

There’s been an assault by the president and his administration on regulations that protect workers in so many ways…Health and safety regulations that protect us from things like…beryllium and silica. Overtime regulations that would have brought overtime to 4 or 5 million people. Consumer protection regulations. Regulations on Wall Street. He’s done away with a number of those things.

Labor seems so unimportant to the current administration that no Labor Day recognition can be found on the White House website.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

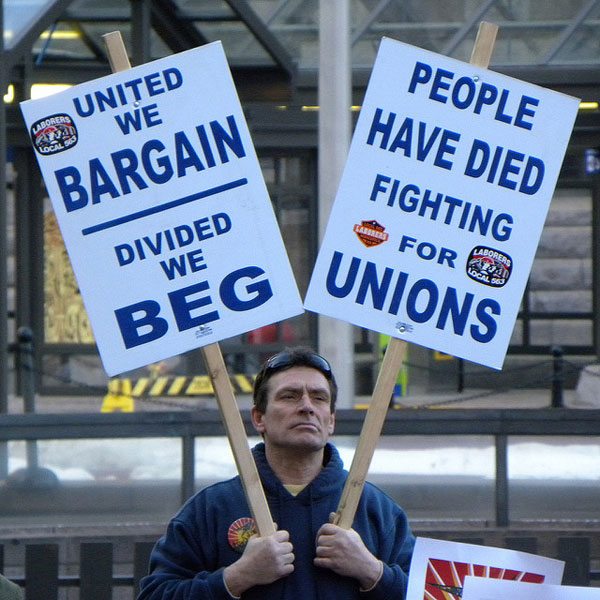

Americans seem to increasingly view unions as important to responding to this problem. The public’s view of unions has strengthened, reaching its highest positive level since 2003. In the most recent survey from Gallup, more than 60 percent of American adults approve of unions, and 39 percent would like them to become more influential—the highest number in the 18 years Gallup has been asking this question. Likewise, the 28 percent who want union power to decrease comes in at the fewest that Gallup has seen.

While their image may be stronger, unions have also seen their power and membership wane. At the start of this year, organized labor represented only 10.7 percent of the workforce, compared with more than 20 percent in 1983. More than half the states now have open shop laws that limit union membership and influence. This is a trend that Americans expect to continue; according to the Gallup poll, despite strengthening public approval, the public predicts that the strong political forces arrayed in opposition to unions will cause them to further weaken in the coming years.

Some workers saw Labor Day 2017 as a time to work to reverse this trend. Under the banner of Fight for $15, strikes, rallies and marches were held in 300 cities across the country to demand attention be paid to the worsening economic circumstances of low wage workers. In Memphis, organizers told WREG that the protest was “not just for $15 an hour, but for union rights in order to fix the economic and political systems in the U.S. that are rigged to benefit big corporations over working people.” Speaking to KHSB, Bridget Hughes, a fast-food worker and an organizer of the rally in Kansas City, Missouri, put the protest in the context of the long history of Labor Day: “Hundreds of years later, we are continuing that tradition and we’re striking out not only to demand $15 an hour, but union rights, protection and a voice in our job.”

According to the U.S. Department of Labor website, Labor Day was established to recognize American workers’ essential contribution to bringing the nation “the highest standard of living and the greatest production the world has ever known.” In 2017, for many workers, the value of their contribution seems forgotten and devalued. What can change this picture?—Marty Levine