August 26, 2017; Birmingham Times

If the U.S. Census does not provide an accurate picture, the federal government’s allocation of $600 billion cannot be targeted effectively. The organizations, many of them nonprofit, that depend on federal funds may find them no longer available, and programs that rely on those funds to fulfill their missions and perform the work of government will feel the pain. On a political level, an inaccurate census will lead the redistricting process that follows each census to give us badly drawn congressional and state districts that do not fairly represent our citizenry. Without prompt action, we’ll have to live with significant problems for at least a decade.

Speaking to the Birmingham Times, Terri Ann Lowenthal, former staff director of the House Census and Population Subcommittee, described the importance of completing the Census effectively: “A good census is a sound investment in everything we hold dear in this country—a representative democracy, government and elected officials that are accountable to the people, and business and industry investment to drive economic growth, good jobs, and innovation.”

Robert Shapiro, chairman of the economic and security advisory firm Sonecon and a Senior Policy Fellow at the Georgetown University McDonough School of Business, described the impact of a flawed Census for the Brookings Institution.

Without an accurate Census, many states and cities will be denied the full funding they deserve and need, and the federal government will have to fly blind for a decade across a range of important areas. Moreover, many businesses also rely on decennial data, from retailers and commercial real estate developers to the banks that finance them. Data on the demographics and locations of potential customers not only inform their planning and investments. In some cases, the data actually make their projects possible, for example, when an investment qualifies for special tax treatment if it occurs in places with certain concentrations of low or moderate-income households.

Yet, neither the president nor Congressional leaders seem concerned that the census is in deep trouble.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Problems began in 2014 when, over the objections of the Obama administration, the Republican-controlled Congress required the Census Bureau to do its work with limited funding. The budget cap was set at $12.5 billion, the same amount that had been spent a decade earlier. To live within this constraint, the Census Bureau cut corners and canceled plans to improve accuracy. According to Brookings, the Bureau “aborted a planned Spanish-language test census and didn’t test or implement new ways to more accurately count people in remote and rural areas. Census also ended its plans to test a range of local outreach and messaging strategies to get people to fill out their census forms, which are crucial to minimizing undercounts in many minority and marginalized communities.”

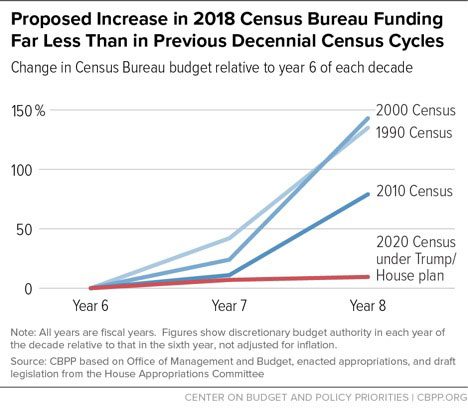

With a new administration in office, matters worsened. President Trump took 10 percent away from the Census Bureau’s already difficult 2017 budget and proposed that the 2018 budget remain at this reduced level. In normal times, the Census Bureau would expect to increase spending in the years prior to implementation; now, they were scrambling to further reduce costs while still producing an accurate count. Adding insult to injury, longtime and well-respected Census Director John Thompson resigned effective in June. This critical leadership position remains vacant, as the Trump administration has yet to nominate a replacement.

With little time to finish preparations, the Census Bureau is in trouble. The Government Accountability Office is so concerned that it added the 2020 Census to its current High Risk List, which it produces at the beginning of each new Congressional term to identify “agencies and program areas that are high risk due to their vulnerabilities to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or are most in need of transformation.” The GAO judged that there had been little progress in implementing efforts to complete an accurate count within the cost structure the President and Congress has imposed. It found that of the “30 recommendations to help the Bureau design and implement a more cost-effective census for 2020…only 6 of them had been fully implemented as of January 2017.”

While the philanthropic and nonprofit communities cannot do what the administration and Congress have been unwilling to do, they can mitigate the problem by creating community-based programs targeted at those at risk of being undercounted. In a recent issue of Responsive Philanthropy, Vanita Gupta, president and CEO of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, wrote an article that highlighted the importance of creating a necessary level of trust in the process itself. In it, former Census Bureau director Kenneth Prewitt said, “Of the many things necessary for a successful census, none rival ‘trusted voices’ that reassure Americans anxious about the government asking questions.’”

Nonprofit, community-based programs can be just those voices for communities at risk. According to Gupta, “When it comes to the census, there are no do-overs—we have only one chance this decade to get it right.”—Martin Levine