This article comes from the summer 2018 issue of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Nonprofits as Engines of a More Equitable Economy.” It was first published on July 25, 2018.

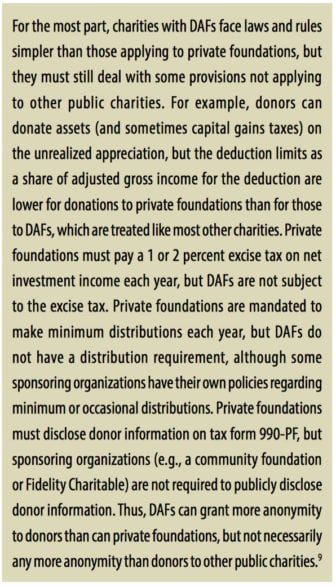

The Nonprofit Quarterly is by no means convinced that there is widespread abuse in donor-advised funds—but do we believe that the conditions exist for widespread abuse? That is a different proposition. There are two categories of concern that some advocates would like to see answered with regulation: the first has to do with the establishment of systems of accountability that look into the transactions of individual funds, and the second is what such a sight line might reveal—for example, overvaluation of noncash contributions, inactivity in disbursement of funds, and transfers of funds from private foundations in an attempt to bypass their payout rates. Thus, the first concern about opacity can lead to the polarization we now see about whether or not the field is in need of regulation, because the concerns of DAF skeptics are not disprovable while DAF sponsors see the veil as being of value to the donors they serve. Is there a way forward other than waiting for the almost inevitable scandal to catch the attention of Congress? We think so.

Background

A donor-advised fund (DAF) is defined as “(1) a fund or account owned and controlled by a sponsoring organization, (2) which is separately identified by reference to contributions of the donor or donors, and (3) where the donor (or a person appointed or designated by the donor) has or reasonably expects to have advisory privileges over the distribution or investments of the assets.”1 Donor-advised funds tend to be held at three different types of institutions: community foundations, commercial funds established by investment firms, and charities serving a particular field or need.

To establish a little background, while donor-advised funds have by some accounts been around since 1931 (when the first such fund was started by the New York Community Trust, by its own claim), DAFs only started to spread significantly since the Tax Reform Act of 1969, when Congress enacted regulatory reform (including reduced tax benefits and payout requirements) on private foundations.2 Given the new constraints, community foundations (which were designated public charities rather than private foundations) realized that they could provide donors with a beneficial alternative (to foundations) by offering a relatively individualized giving vehicle for donors through the donor-advised fund model. Donors would get all the tax benefits of a transfer to a public charity, but there would be an understanding that the funds would be segregated and the donor would retain functional control over the distribution (and sometimes investment) of the donated funds.

In 1981, the category of donor-advised funds was written into law.3 At that point, DAFs began to proliferate largely in community foundations, but they have only become controversial since commercial financial firms entered the field as sponsors in the early 1990s, establishing their own public charities to receive, hold, and dispense the funds.4 This placed them in direct competition with community foundations, and there was a good deal of hostility that built up. That hostility has since dissipated to some extent as community foundations realized that the marketing of DAFs done by the financial services industry assisted the growth of DAFs in community foundations as well. But the discomfort that others feel with the vehicle in general has grown, along with the very rapid expansion of the field, which is maintained below the sight line of the public. Tracking the extent of any problem (or whether a problem even exists) is made difficult by the veil provided by sponsors—which allows DAFs to be almost entirely opaque. This raises questions about accountability and access, and it should come as no surprise that these questions are emerging even as these funds grow relatively astronomically in numbers and dollar value.

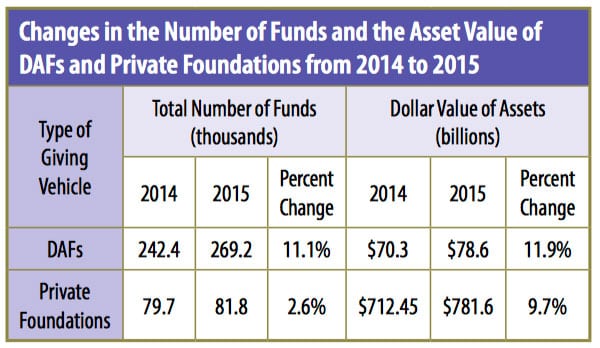

DAF asset values more than doubled between 2010 ($33.6 billion) and 2015 ($78.6 billion).5 Year over year, as you can see below, the growth has been nothing short of phenomenal while all of giving as a proportion of disposable income has stayed relatively stable.6

Another grounding issue for those trying to make sense of policy needs for this vehicle is that DAFs have a dual character that leaves them sitting oddly between foundation and individual giving. You must approach the individual (or vice-versa), but the grant is finally made by the DAF sponsor, which retains real ownership/stewardship over funds that have been transferred to the DAF. Lila Corwin Berman calls this an “intersection of these two modes—charitable endowments and individual donor control over public charitable dollars.”7

This plays out to hold the sponsor responsible for its own transparency as a whole entity while obscuring the activities of the individual funds. Tax guidelines promulgated in [the Pension Protection Act of] 2006 require each donor-advised fund sponsor to report the total number of funds, total assets in the funds, and total contributions to and from the funds on their Forms 990, but any information on the individual funds themselves, regardless of size, is obscured.8

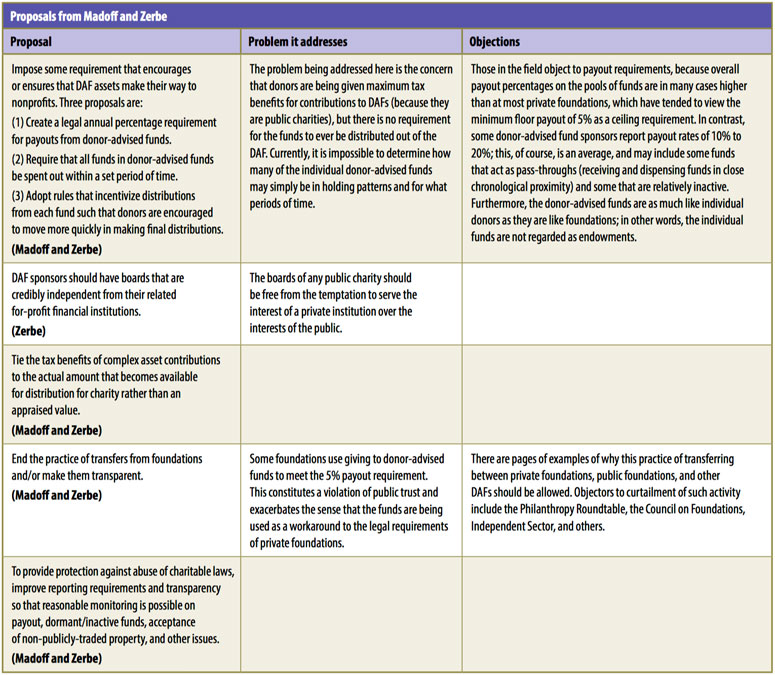

To explain what the issues are, we invited two advocates, Ray Madoff and Dean Zerbe, well known for their criticisms of the DAFs field, to provide their takes on what needs regulatory attention. We also invited others to write about why such broad-based congressional attention was not now needed and to speak up about what additional, but more limited, regulations were needed, but we mostly got demurrals. So, we were stuck trying to make some sense of what may be priority issues for regulation, which we have done below with the benefit of prior analyses from the Urban Institute and others. The issues we have identified as deserving of attention are not the issues you may most commonly hear from nonprofits, by the way, which have to do with the ability to identify donors with DAFs; but they are the issues where we have determined the most abuse might be occurring.

None of the proposals advanced below have to do with affording more access for nonprofits, which is what bugs many organizations. When complaining about donor-advised funds, nonprofits generally talk about the inability to access the names and contact information of fund advisors and related information about grant types, amounts, and so forth. That particular issue flows from the individual giver aspect of the DAF identity. Despite the fact that the money is being held as charitable funds and a deduction has been taken, there is no requirement for the publishing of material that identifies the giver, and the funds see that prospect as being a potential wet blanket on the proposition they are offering donors—that of nailing the donor down to a dollar-giving intention but not revealing that publicly nor requiring any precommitment to any particular nonprofit.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While the funds are championed as democratizing giving, there are some indications that the donors continue to act more like high- than low-end givers; as the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at IUPUI reports, “there are some similarities between donor-advised fund granting patterns and the national distribution patterns…there are even more similarities when donor-advised fund granting patterns are compared to data on individual donors only.”10 Some may feel that providing a veil for high-end givers primarily is unfair treatment; that veil, in fact, stands directly in the way of our understanding the extent of some of the problems identified by Madoff and Zerbe. Thus, no one really knows the extent of the problem of private foundations avoiding the 5 percent payout rate through the use of donor-advised funds, but they have been left trying to surmise it through the use of other information, as is described here by IUPUI:

…researchers endeavored to understand why giving to public-society benefit (PSB) from donor-advised funds was higher than the national trendline. In 2015, giving to PSB accounted for 16 percent of donor-advised fund grant dollars, while PSB garnered 8 percent of total giving in the same year according to Giving USA 2017.

The public-society benefit subsector, as defined by Giving USA, is a collection of many distinct charities including national donor-advised funds, United Way chapters, Jewish appeal funds and federations, veteran’s affairs organizations, civil rights nonprofits, and others.

Upon closer inspection of the public-society benefit subsector data, we found that a certain proportion of granting from donor-advised funds was going to other organizations classified as donor-advised fund sponsors (DAF-to-DAF granting).11

This particular problem of private foundations using contributions to DAFs to bypass payout rules should be seen as especially egregious, since it may not be illegal but certainly flouts the intent of the payout requirement. But there is no way to determine the extent of the problem without extraordinary efforts. Of course, there is a way for donor-advised fund sponsors to help make the field more transparent by funding more independent research themselves, based on increased access to the data. See more on this idea below.

…

It is unclear what the congressional appetite is for the regulation of DAFs. Former Michigan Congressman David Camp’s proposal in 2014 to levy an excise tax on DAF funds not distributed within five years of contribution has been largely left for dead.12 However, as evidenced by the recent rules regarding university endowments and sports seating, Congress does appear largely mindful of concerns over the relationship between charitable tax benefits and the public good.13 While Congress appears largely uninterested in donor-advised funds, it is demonstrably increasingly and critically interested in endowments that do not accrue properly to the benefit of the public. Donor-advised funds that aren’t fluid are alike enough to endowments to pose a threat to the entire field by providing rich soil and a veil for misbehavior in that sweet spot of congressional attention. Additionally, it is in the best interests of the whole sector to understand how these bodies work to ease or dam the flow of charitable giving into nonprofits that provide benefit to our communities and society.

The one issue that is most talked about as in need of policy change is the issue of payout rates, which has compared very favorably to foundation payouts—but not so favorably, of course, to direct giving, if you assume that the same amount would have been given elsewhere.

In any case, in the absence of transparency, one could assume that none of the proposals have merit or almost all of the proposals have merit—and therein lies a big problem. It should be said that many DAF sponsors have already begun implementing internal rules that answer some of the concerns—for instance, some have rules in place to prevent funds from remaining dormant for too long. Fidelity Charitable, for example, sweeps funds that have been dormant for three years or more, and grants the money itself in individual funds. But codifying such practices and fine-tuning them to close any loopholes that have opened up during this period of explosive growth will either be done by the field in a way that lends itself to strict fieldwide standards or may eventually end up in the hands of Congress when we least expect it (and possibly following a scandal or two).

Finally, the whole field would benefit from independent research that examines a number of key questions, identifying patterns that violate standards already in law or regulation. This proposal was advanced in 2015 by the Urban Institute, in their paper “Discerning the True Policy Debate over Donor Advised Funds,” in which a call was issued to national DAF sponsors “to share data with independent third-party researchers in ways that could accommodate privacy concerns.”14 In fact, such access could provide the robust research and data that would allay regulators’ concerns—if no cause for concern exists.

In the end, as former Massachusetts Attorney General Scott Harshbarger asserts in the introduction to this section, the field itself has an opportunity to achieve the best balance of imposed and voluntary accountability measures if it moves toward accrediting DAF sponsors, but it cannot expect the public to continue to take it on faith that these bodies are managed to the highest ethical standards without more assurances than exist now.

Notes

- “DONOR-ADVISED FUNDS GUIDE SHEET EXPLANATION,” Internal Revenue Service, U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 31, 2008.

- “What is a Donor-Advised Fund (DAF)?,” National Philanthropic Trust, accessed June 16, 2018; Donor Advised Fund Timeline: Milestones in the History of DAFs (Arlington, VA: Council on Foundations); and “SIMPLIFY YOUR CHARITABLE GIVING. WE DO ALL THE WORK,” The New York Community Trust, accessed June 16, 2018.

- Giving USA Foundation, The Data on Donor-Advised Funds: New Insights You Need to Know (Indianapolis: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at IUPUI, 2018), 14.

- Kevin Johnson, “The Economist Weighs in on Donor-Advised Funds: A Philanthropic Black Box?,” Nonprofit Quarterly, March 28, 2017.

- 2016 Donor-Advised Fund Report (Jenkintown, PA: National Philanthropic Trust, 2016).

- Ibid.

- Lila Corwin Berman, “Donor Advised Funds in Historical Perspective” (paper presented at the Forum on Philanthropy and the Public Good, Washington, DC, October 23, 2015).

- “New Requirements for Donor-Advised Funds,” Internal Revenue Service, accessed June 15, 2018.

- Ellen Steele and C. Eugene Steuerle, Discerning the True Policy Debate over Donor-Advised Funds (Washington, DC: Tax Policy and Charities Initiative, Urban Institute, October 2015).

- Giving USA Foundation, The Data on Donor-Advised Funds, 30.

- Ibid., 29.

- Grace Allison and Jessica Baggenstos, “Camp Tax Reform Proposal & the Income Tax Charitable Deduction,” eReport, The American Bar Association, April 2014.

- CASE; “The College Athletic Seating Deduction is Out. Here’s What We Know (So Far),” blog entry by Brian Flahaven, January 26, 2018.

- Steele and Steuerle, Discerning the True Policy Debate over Donor-Advised Funds.”

Disclosure: The Nonprofit Quarterly has recently received a grant from The Fidelity Charitable Trustees Initiative.