Nonprofits often aim to disrupt systems that no longer work for people, especially the most vulnerable among us. But this work is often grueling and lonely, as the radical social change many nonprofits seek may seem elusive.

In our latest Tiny Spark podcast, we examine how one nonprofit has successfully disrupted and challenged a powerful national institution by remaining committed to slow, tedious work, year after year.

The Innocence Project opened its doors in New York a mere quarter-century ago. Since then, it has expanded across the nation and the globe. Each year, Innocence Project attorneys and law students carefully examine a slew of suspected wrongful conviction cases, poring over court documents and transcripts, visiting prisons, often working for years to see a single case through the criminal legal system.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Over time, the cumulative impact of the nonprofit’s work has been significant. To date, the Innocence Project says some 367 people in the US have been exonerated by DNA testing alone; of those, 21 had served time on death row. With every successive exoneration, the Innocence Project has been building a larger case in the court of public opinion, raising serious questions about the use of death penalty, casting doubt on the efficacy of forensic science testimony, and even challenging the integrity of the criminal legal system itself.

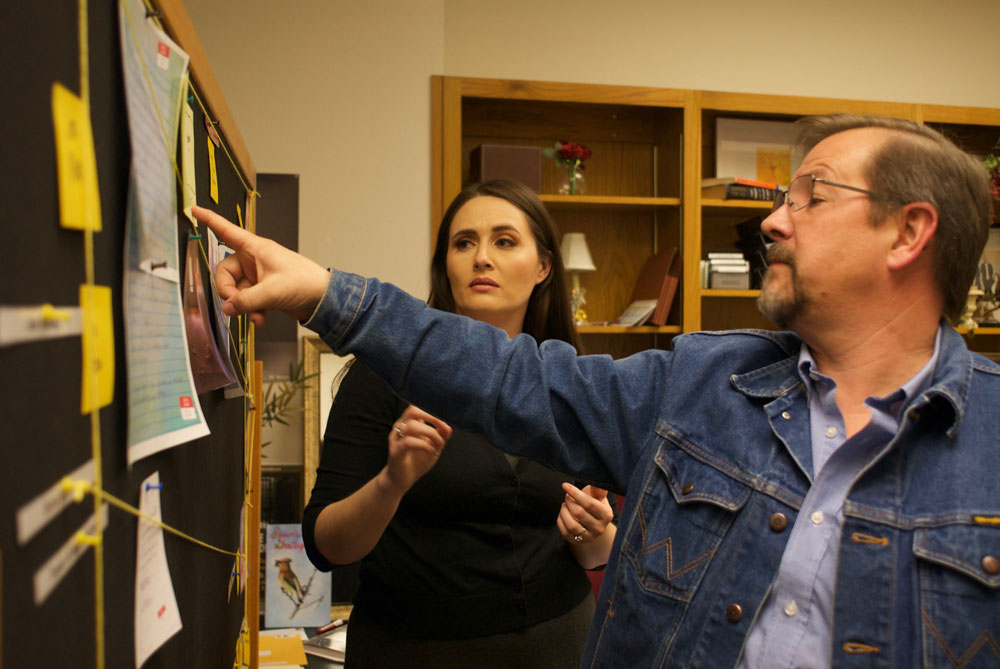

Despite their many victories, Allison Clayton, deputy director of the Innocence Project of Texas, says she faces pushback from colleagues inside the criminal legal system on a regular basis. In fact, she says it’s the hardest part of her job. “It’s dealing with injustice and indifference to injustice, day in and day out,” she says. “The abyss that we look into every day is a justice system that gets it wrong routinely, and people who just don’t care. It’s sickening.”

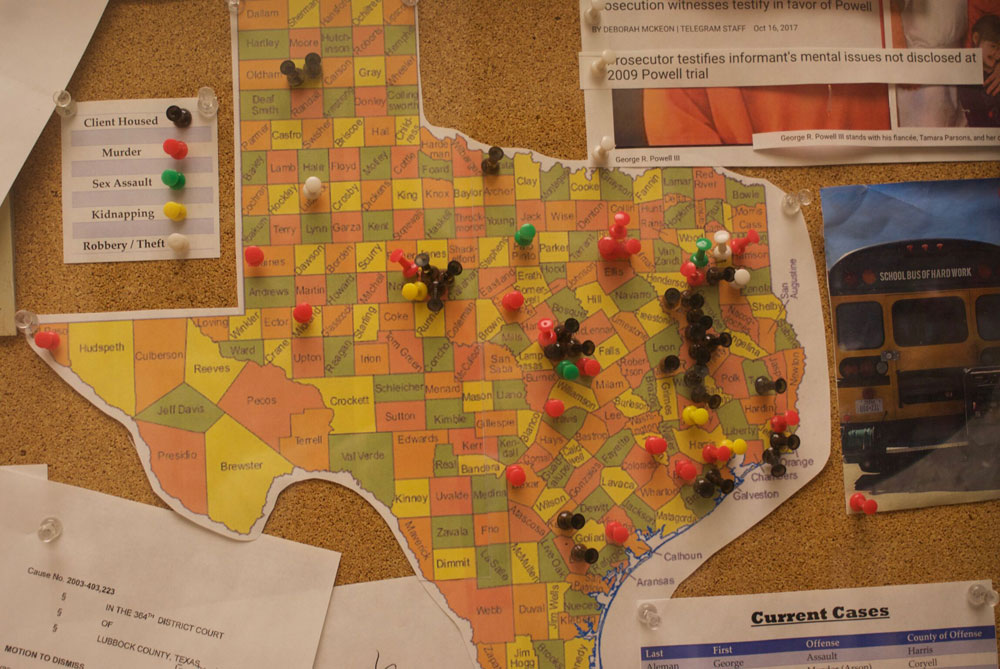

We spend time with Clayton as she works with law students at the Innocence Clinic at Texas Tech University’s School of Law in Lubbock, where each student juggles six or seven cases at a time. We hear from lawyers working through the minutiae of their cases, examining how flaws in forensic science testimony have led to wrongful convictions, and we hear from the Texas chapter’s executive director Mike Ware, who describes the conundrum he often faces because they are so inundated with requests for help. As a result, he has to make hard choices about which cases to take on and which ones to let go.

“At some point you’ve got to make a decision,” he explains. “What is the best, most ethical way to handle a case that, you know, you can see it…There was not much evidence to convict him. There is no evidence to exonerate them. Do you just you close the case and tell them? Or do you leave it open and hope something comes up?”

Despite the setbacks and frustrations inherent in this work, Ware says there is one thing that keeps him at it. “The successes,” he says. “The successes are so spectacular and rewarding.”

Additional Resources:

- Innocence Project Texas website

- Innocence Project (national) website

- The Texas Tribune: “How some see Texas as the ‘gold standard’ against wrongful convictions.”

- Chicago Tribune: “Why the innocent end up in prison”

- Slate: “Reasonable Doubt: Innocence Project Co-Founder Peter Neufeld on Being Wrong”

- Mother Jones: “How Many Innocent People Are in Prison?”