Editors’ note: This article, first published in print during May/June 2018, has been republished for Nonprofit Quarterly with minor updates.

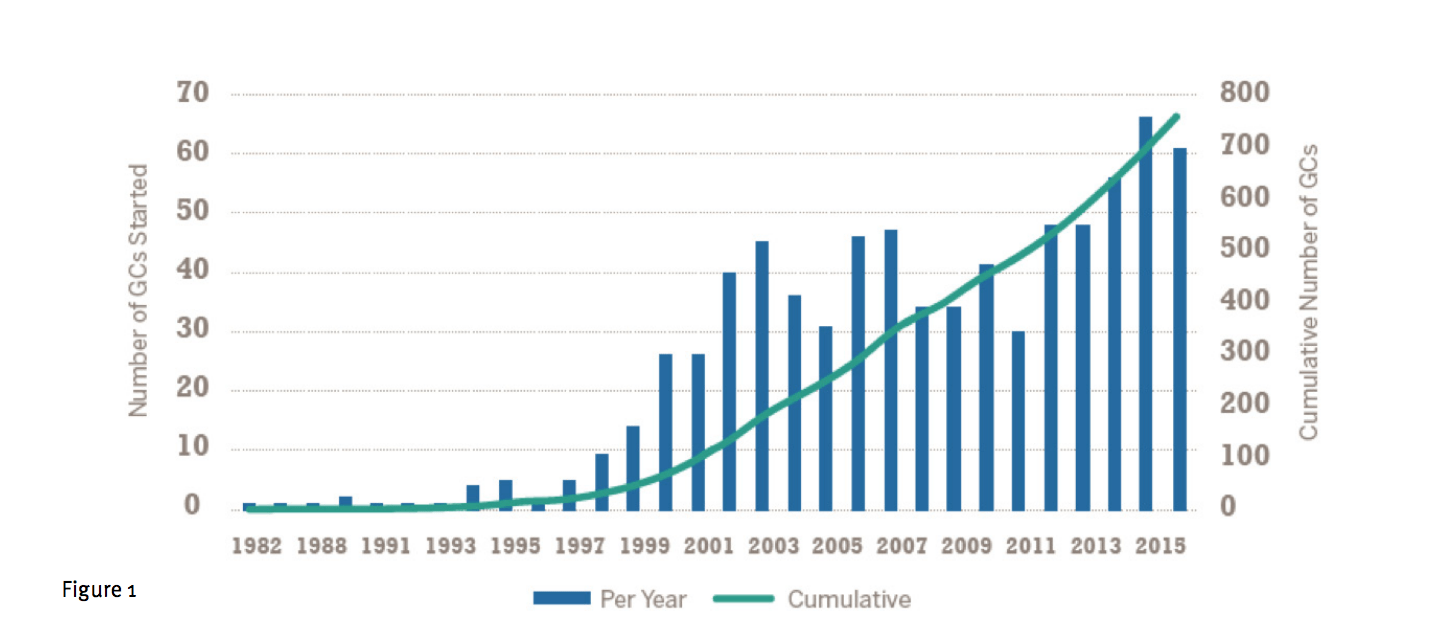

A CONSTANT DRIVE IN FUNDRAISING IS TO IDENTIFY and reach new donors, to expand our base of support. One place to look, especially for local nonprofits, are giving circles (GC), increasingly popular tools for donors to come together to pool their funds and find and give to causes they care about. According to research I conducted with Angela Eikenberry, Julia Carboni, and Jessica Bearman, fellow members of the Collective Giving Research Group (CGRG), giving circles and other collective giving groups have tripled in number since 2007 to over 1,600 active circles working in all 50 states today. (See Figure 1 on next page.)

Giving circles and similar models of collaborative giving entail groups of individuals who collectively donate money and sometimes unpaid time to support organizations or projects of mutual interest. We define them as giving vehicles where members principally come together to pool and give out donations through a process in which they have a say in how funding is given and which organizations or projects are supported. These circles range in scale from a handful of friends coming together to each contribute $50 or $100 a piece to make a $1,000 grant, to thousands coming together to give out hundreds of thousands a year, or even

THE DIVERSITY OF SCALE AND SCOPE OF GIVING CIRCLES IS WHAT MAKES THEM BOTH EXCITING NEW VEHICLES IN THE PHILANTHROPIC LANDSCAPE AND CHALLENGING ONES TO DEVELOP A CULTIVATION STRATEGY FOR.

Figure 1

small groups coming together to give $1 million or more each through a collective process. The diversity of scale and scope of giving circles is what makes them both exciting new vehicles in the philanthropic landscape and challenging ones to develop a cultivation strategy for.

As a first step towards helping the field better understand this increasingly popular approach to giving, the CGRG, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the Women’s Philanthropy Institute at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy and from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, conducted the first investigation into the scope and scale of collective giving groups in the United States in almost a decade resulting in a recent new report, The Landscape of Giving Circles/Collective Giving Groups in the U.S.–2016, which can be found at bit.ly/giving circles report. Data presented in this article are drawn from this report unless otherwise noted.

The Giving Circle Landscape

We estimate that giving circles engaged at least 150,000 donors in all 50 states in 2016 and have given as much as $1.29 billion since their inception. Out of 358 GCs who shared data about their giving in 2016, they moved a combined $28 million of which 85 percent stayed in their local communities. A majority of giving circles are created around a particular identity— including groups based on gender, race, age, and religion. Almost half of all circles today are women’s circles and our research shows significant growth in Jewish, Asian/Pacific Islander, African-American and Latinx circles in the past decade. Thy have proven to be a powerful tool to democratize and diversify philanthropy, engage new donors and increase local giving which has brought rising attention to giving circles as another possible cultivation prospect for nonprofit leaders

across the sector. As we consider fundraising from giving circles, some aspects of the diversity of these circles is important to keep in mind:

- Giving circles are becoming more inclusive with donors from a wide range of income levels.

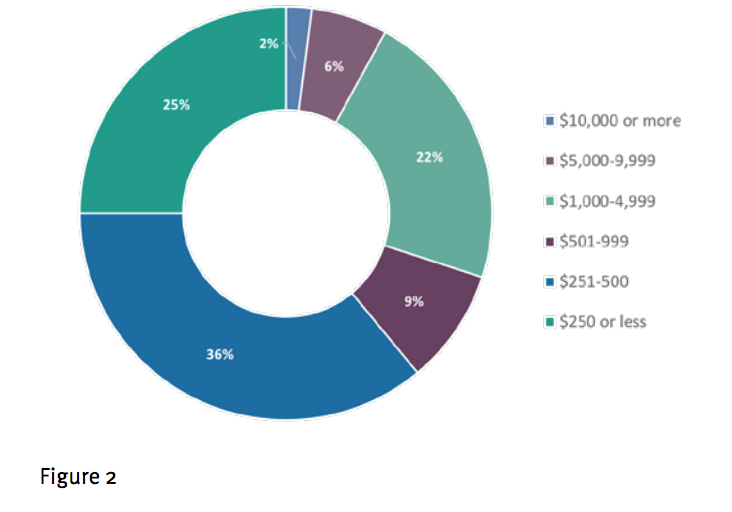

Giving circles have always provided avenues for those without substantial means to participate in significant giving, but this latest research suggests that GCs now attract members from a wider range of income levels than ever. Today, minimum dollar amounts required for participation range from less than $20 to $2 million, and the average donation amount was found to be $1,312—compared to $2,809 in 2007. (See Figure 2 below.)

Figure 2

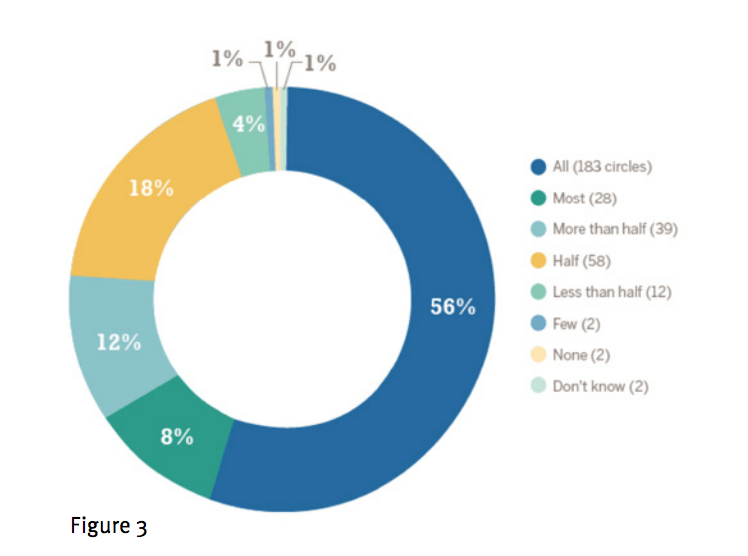

Figure 3

- Women dominate giving circle membership, making up 70 percent of all members.

This collective model of giving is particularly popular among women. While men have a presence in 66 percent of giving circles, they are only the majority of members in 7.5 percent of groups. (See Figure 3 above.)

- Issue priorities among giving circles mirror broader priorities of the American public.

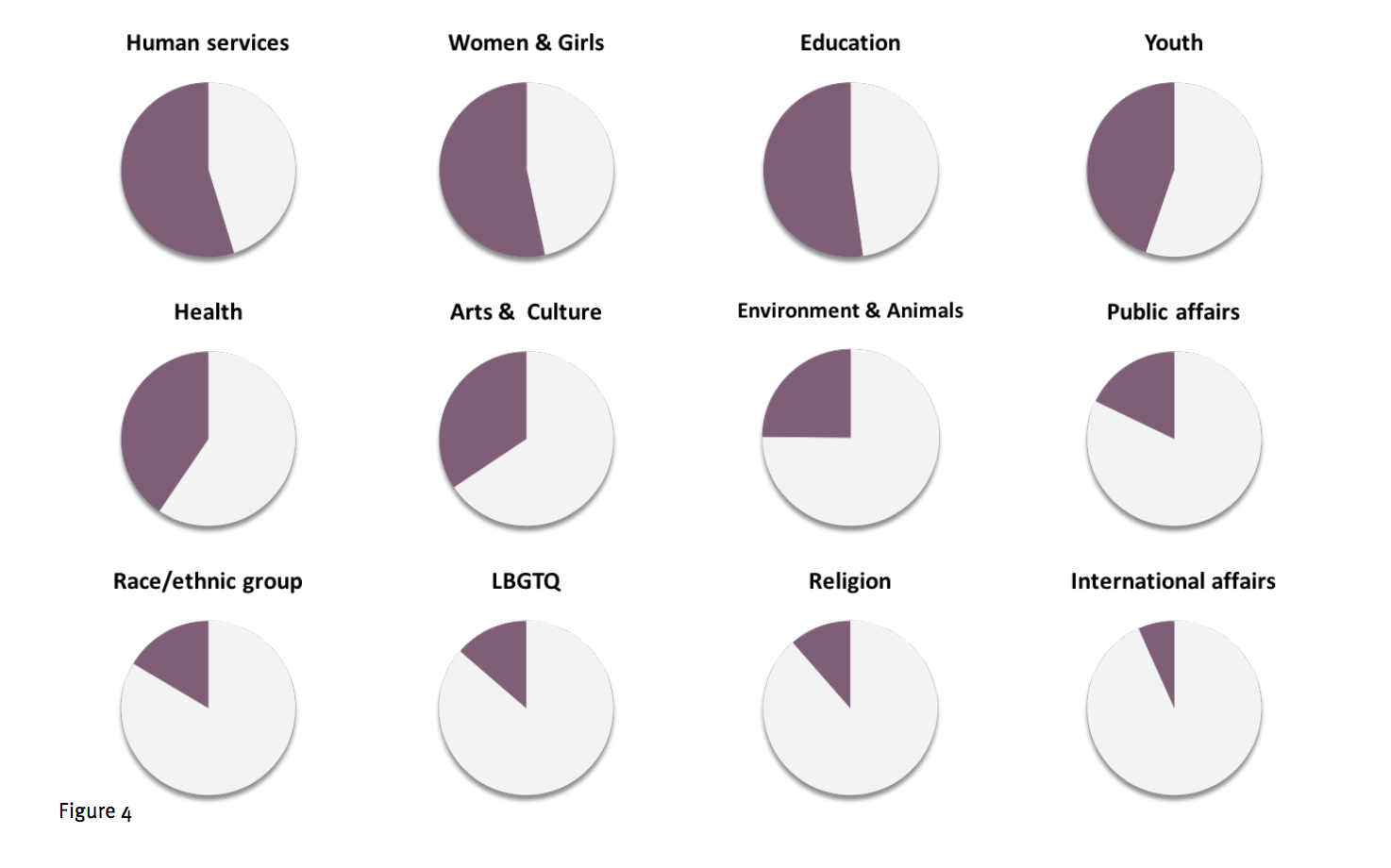

Most giving circles give to their local communities and the issues that they fund are very similar to broader national trends with human services as the most commonly cited priority. The funding of projects related to women and girls follows, which is higher than national averages likely due to the high number of women’s circles, followed by other traditional national priorities of education, youth and health. (See Figure 4 below.)

Fundraising from Giving Circles

The fist key to raising funds from a giving circle is to identify one or more that are a good fit to support your work. The CGRG has compiled a basic listing of all publicly-identified giving circles, which can be accessed at bit.ly/Giving Circles List. This site is probably the best place to begin your search. Additionally, since over 50 percent of all giving circles are hosted by a community or public foundation, if you run a local organization it’s worth checking to see if your local community foundation, United Way, Jewish Federation, women’s fund or other public foundation hosts one

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Figure 4

or more circles. Finally, and especially if your work focuses on supporting women and girls or a particular identity community with many giving circles (Jewish, Asian/Pacific Islander, African American and Latinx communities), reviewing the member circles that are part of one or more national networks can help you identify local and national circles that may fund your work. A listing of giving circle networks has been developed by Amplifier (a network of Jewish giving circles) and is available at amplifiergiving.org.

Once you’ve identified one or more prospective circles that might be a good fit, your next step is to determine how to approach them for support. Many giving circles have formal application processes that they run independently or in partnership with their hosting foundation, and a few utilize a shared application

REMEMBER THAT GIVING CIRCLES ARE A FORMAL OR SEMIFORMAL GIVING STRUCTURE OF INDIVIDUAL DONORS, AND THEIR FUNDING PROCESS CAN OFTEN FEEL LIKE A HYBRID OF THE INFORMAL RELATIONSHIP-BASED CULTIVATION OF A MAJOR DONOR AND THE FORMAL APPLICATION AND REVIEW PROCESS OF A COMMUNITY OR PRIVATE FOUNDATION.

like the one run by Amplifier for Jewish giving circles. Other circles operate on a more informal basis, and the best way to connect with them is to simply reach out to share information about your work and request that they consider you in the future for support. It’s also possible that one or more of your current donors and other stakeholders are already members of the circle and would be willing to suggest your organization as circle members consider possible grantees.

As you pursue support from giving circles, a word of caution about the importance of realistic expectations. Most circles only give out one-year grants (with the notable exception of a few formal processes like that of Social Venture Partners), and have a practice if not a formal requirement of changing grantees annually as they learn about new groups and follow the collective priority setting of their membership. Also, the application and review processes of giving circles run the gamut from very informal to highly structured and are not always matched to the level of funding. Some circles prioritize learning for members and may ask nonprofits to go through an extensive review process for the sake of that education, which may not align with the scale of work required to raise an equivalent foundation grant. Remember that giving circles are a formal or semiformal giving structure of individual donors, and their funding process can often feel like a hybrid of the informal relationship-based cultivation of a major donor and the formal application and review process of a community or private foundation.

After the Gift

One of the biggest hopes of nonprofit leaders as they engage with a giving circle is that, beyond receiving financial support, they may find the opportunity to engage the circle members as possible new individual donors, volunteers, and eventual leaders in their work. Indeed, in our interviews with GC leaders across the country we heard regular stories about members discovering a nonprofit through the circle and later becoming ongoing donors, volunteers, and even board members. Based on a series of interviews with nonprofit leaders about the particular dynamics of GC fundraising, Angela Eikenberry reports that giving circles “also can bring to the funding recipient the introduction of giving circle members with contacts to others in the community, new volunteers, a seal of approval, and other capacity building resources.”1 However, nonprofit leaders who have received support from giving circles have also noted that building these relationships can be challenging as Eikenberry later noted in the same reflection:

Over half of those interviewed brought up that it is difficult or impossible to connect with individual donors in the giving circle—either by design or by default. Some giving circles actively discourage funding recipients from following up with or cultivating their members for individual gifts by not sharing the member mailing list or not even allowing funding recipients opportunities to interact with giving circle members. Others noted that they were not explicitly told they could not cultivate individual members, but they got the impression that it was not acceptable behavior.”2

1 Eikenberry, A. (2007) Giving Circles and Fundraising in the New Philanthropy Environment, Final Report. Association of Fundraising Professionals.

2 Ibid.

What then is a nonprofit leader to do? As with all fundraising, communication and persistently polite cultivation are key. Make sure to offer thoughtful and clear reports on all giving circle reports as these are generally shared back with the membership, offer highlights of key successes to your circle contacts that are

FINDING BOTH QUICK AND EASY AND DEEP AND MEANINGFUL OPPORTUNITIES FOR VOLUNTEER ENGAGEMENT ARE ALWAYS CHALLENGING BUT AS THEY EMERGE, GC MEMBERS ARE A PRIME AUDIENCE TO RECRUIT.

in easily shareable formats for them to disseminate, and offer invitations to donor briefings and appreciation events for all circle members (not just one representative) if possible.

On the flip side, some circles proactively seek to engage with their grantees more deeply and when those possibilities exist, smart nonprofit leaders take advantage of this support. In an evaluation of the Social Venture Partners (SVP) model, which proactively matches members to volunteer with supported nonprofits, Guthrie and Bernholz found that almost 60 percent of SVP members who got involved with an individual nonprofit reported that they made additional financial contributions beyond their gif through SVP, and the majority indicated that they expected to keep volunteering and or donating to the group after it had completed its cycle of support.3 Finding both quick and easy and deep and meaningful opportunities for volunteer engagement are always challenging but as they emerge, GC members are a prime

3 Guthrie, K., Preston, A., & Bernholz, L. (2003). Transforming philanthropic transactions: An evaluation of the first five years at Social Venture Partners Seattle.

audience to recruit. Additionally, some nonprofits have reported success with other collaboration opportunities such as asking circle members to share personal stories of why they are excited about the work to promote an annual campaign or promoting the group to their networks as part of a giving day.

Giving Circles: The Bottom Line

As their popularity continues to rise, connecting to GCs in your community or those supporting the issue you work on can offer a new type of funding support. Unless you get support from a larger formal GC like an Impact 100 or SVP chapter, these grants are unlikely to be transformative for your organization, but they can bring in valuable new dollars, serve as a seal of approval especially in local contexts, and potentially connect you to new donors and broaden your base of support. Ultimately, fundraising from giving circles offers yet another way to engage new donors and build support for your work… the perpetual work of every nonprofit fundraiser and leader.