This article is from NPQ’s fall 2015 edition, “Making Things Work: Considerations in Nonprofit Strategy.”

For citizen activists at the local level, today’s political landscape may seem daunting, if not downright intimidating. There are a number of trends that seemingly run against the interests of local community and neighborhood groups. In the post–Citizens United era, the sums being spent in the political world stagger the imagination. Corporate political power has never appeared greater. Partisanship has turned politics—never a polite exercise—into something akin to warfare. Modern political campaigns now rely strongly on sophisticated database management, in turn facilitating scientifically targeted appeals to narrow slices of the population. Finally, fiscal stress at every level of our federal system makes it difficult to move policy in new directions, even if there is widespread agreement on the need for a new approach. To paraphrase Dickens, it may just be the worst of times.

Yet, for those working in city politics, there is reason for optimism. Yes, cities are feeling plenty of fiscal stress, but the other trends are not as evident in cities as they are at the state and national levels. Urban advocacy does not depend on large-scale spending or overcoming deep partisanship or using sophisticated Internet data gathering. Old-fashioned door-to-door organizing still works, and research has demonstrated that there are clear attributes of successful but low-cost nonprofit advocacy. Indeed, for activists at the city level, it might actually be the best of times.

Open Cities

Urban advocacy stands apart from Washington politics for a variety of reasons. Most broadly, think of what economists call “barriers to entry.” A new business trying to enter a market may face obstacles that must be overcome before it can compete. Some barriers to entry can be prohibitive—think of the jetliner industry. The capital requirements to sustain a new airline manufacturer while it designs and builds aircraft and before sales can be generated make starting such a business a fool’s errand. For investors, it is better to concede the business to Boeing, Airbus, and the few others in the industry, and use their capital to enter a market with lower entry requirements.

Starting a new, nationally oriented advocacy group with an office in Washington, DC, doesn’t face quite the barrier that a new plane manufacturer would confront, but it is a crowded market. What policy area doesn’t have a surfeit of organizations already pleading their case before Congress and administrative agencies there? It is different in the case of urban- or neighborhood-oriented advocacy groups. The barriers to entry for urban groups are quite low, and even just a modest level of organization and political savvy can yield a substantial payoff.1 Compared to Washington or even statehouses, the capital requirements are negligible. No fancy office like those on K Street or Capitol Hill is necessary; new groups don’t need to hire high-priced lobbyists, and there’s no need for an advertising budget. The citizen groups and neighborhood associations that are involved in urban policy-making are typically run by volunteers working out of someone’s home or from a cheap storefront. Even broader civic associations or public–private partnerships that encompass citizen group stakeholders are inexpensive to maintain, because they are often given free office space by a member company or law firm.

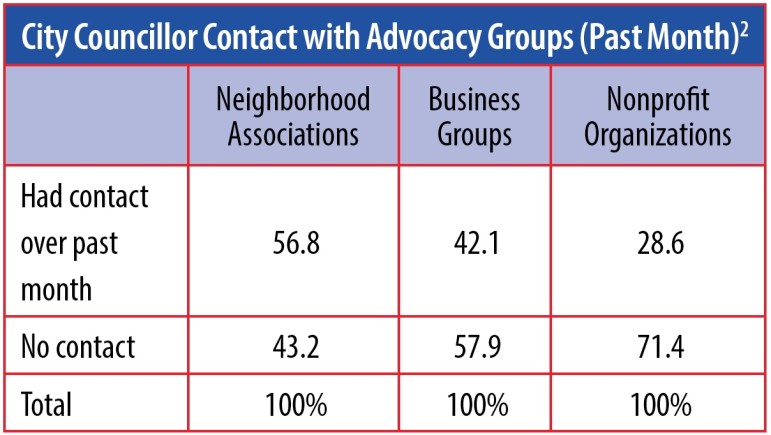

Beyond the modest requirements of organizing is the openness of city government. City agencies and city councils are highly accessible and responsive to meeting with serious advocates representing a geographical or issue constituency. With Texas A&M political scientist Kent Portney, I surveyed administrators, city councillors, and interest group leaders in fifty large American cities. One of the questions for city councillors listed seven different types of advocacy organizations, and each councillor was asked which ones they had had contact with “over the last month or so.” Neighborhood associations were most often noted, with over half of city councillors indicating contact with one or more over the previous month. Business groups, always important in city politics, finished behind neighborhood groups but ahead of a general category of nonprofit organizations (see below).

This pattern was no anomaly. Representatives of all the different types of advocacy groups were asked what happened when they called an official at city hall: How likely was it “that you’ll either get through to that person or that your call will be returned?” For representatives of nonprofits, the likelihood that a call would almost always or usually be returned was 95 percent. The figure was about the same for business leaders, and only modestly lower for neighborhood associations (82 percent). By any standard, this is an impressive level of access to policy-makers. In an alternative test, we asked how often government approaches advocacy groups rather than the other way around. Those results show that while business scores highest on this measure of government-initiated contact, nonprofits and neighborhood associations score well, too.3

All of this begs the question, Why is it that local government is so porous, so open to talking to citizen groups? We know from research on Washington politics that this isn’t the norm: there, a high proportion of interest groups struggle to gain meaningful access to policy-makers.4

One fundamental difference is that local government is much weaker than state or national government, as the resources of the institutions themselves (city agencies, the city council) are modest. Moreover, local government tends not to be controlled by parties or regimes. In Los Angeles, for example, there is nothing close to a regime in power. The city is splintered into a vast array of neighborhoods and ethnic constituencies. Bill de Blasio is mayor of New York City, but there is no de Blasio political machine to be feared and no dominant de Blasio bloc on the city council. Instead, ad hoc alliances and case-by-case coalitions are common in cities large and small.5

Local governments are eager to enlist partners who can help aggregate the resources to move initiatives forward. One study of Chattanooga’s ambitious set of policies aimed at promoting environmental sustainability concluded, “Virtually none of the activities associated with sustainability in Chattanooga have been directed, administered, or spearheaded by a city agency of any sort.”6 Instead, this push came from the local Chamber of Commerce, Chattanooga Neighborhood Enterprise, RiverValley Partners, and many other local organizations. Together, these business and environmental groups pushed programs forward as they tried to reenvision the city and reignite a stagnant local economy.

Social scientists used to conceive of cities as dominated by downtown businesses that worked with the mayor to govern the municipality. This big business–mayor alliance was powerful, and, conversely, neighborhoods were weak. But the nature of central city economies has evolved, and dramatically so: Large-scale manufacturing has largely left cities; new industries that have emerged, such as computers, communications, and biotech, largely prefer the suburbs; and globalization and technology have changed the literal footprint of business enterprise in the United States. In Boston, for example, large banks used to be dominant players in city government, with six Boston-based banks members of a semi-secret body of mayoral advisors.7 Today, there isn’t a single large-scale bank headquartered in Boston, and no bank occupies a central role in leadership of the city. The behemoth that swallowed up many of the other large Boston-based banks, Bank of America, is headquartered in North Carolina and has shown no interest in Boston or Massachusetts politics.

Demographic change in the American city has been even more striking. Majority-minority cities are common today, and the minority population is often a rainbow of different ethnicities. Not surprisingly, the mayors and city councillors who are elected by such voting constituencies frequently mirror those racial and ethnic patterns. The geographic concentration of minorities in many neighborhoods within a city further empowers such communities. New city councillors often arise out of neighborhood groups, using their growing name recognition and networking opportunities to move up the political ladder. In recent years, another demographic change that has emerged is the increasing number of white professionals moving to cities—into new real estate developments in central downtown districts as well as traditional residential neighborhoods.8

What Works?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Although the structural and demographic characteristics of modern American cities offer opportunities for citizen advocacy, there is no assurance that such advocacy will manifest itself. Moreover, even if organizations do materialize to represent citywide or neighborhood interests, there is no guarantee that they will be effective. Business is still present in the city, albeit of a more modest profile, and cities still hunger for new business development and the new jobs and taxes it will create. Land use is the issue area most likely to catalyze business advocacy, and the stakes are high when major real estate development projects are proposed.

Every situation has unique circumstances, but a growing body of research points toward clear correlates of success for citizen groups. The first step is straightforward, but one that leaders are often hesitant to take: organizing with an overtly political predisposition. Citizen groups that populate neighborhoods and represent city-level constituencies are almost all nonprofits, and some adopt the mindset that nonprofit means nonpolitical. An unfortunate misconception is that nonprofits are not allowed to lobby, and, if they do, will get into trouble with the IRS. It is perfectly legal for nonprofits to engage in lobbying legislators or administrators at any level of government; sadly, however, a survey of nonprofit leaders showed that a large proportion believe that it is not.9

One real restriction on nonprofits holding 501(c)(3) status is that they may not donate campaign funds nor endorse candidates. But even in the case of 501(c)(3)s, there are ways of demonstrating support for favored mayoralty or city council candidates without actually formally endorsing them.10 Candidates can be invited to meetings, given space in paper or electronic newsletters, and spoken of favorably in internal communications. Nonprofit leaders can become active in campaigns as long as they indicate in some formal way that they are not acting on behalf of their employer. As individuals, they can donate to candidates and even host a fundraiser.

At the very base of organizational efficacy, then, is establishing an orientation toward aggressive advocacy—a need to fix lobbying as a goal. Jennifer Mosley notes that “the decision to be involved in advocacy comes down to one or two individual leaders in an organization.” Too often, she warns, leaders believe “that advocacy is outside of the organization’s mission” or “[do] not believe advocacy will have meaningful benefits.”11 But this is counterproductive. To be effective in the policy-making arena means leaders must steer their organizations toward advocacy by convincing staff, volunteers, and board members that this is a priority.

Optimally, advocacy is coupled with more than strong expressions of preference. Beyond political support, what city councillors and agency officials find most helpful is research that bolsters their own work. In a study of 1,738 nonprofits, David Arons and I tried to determine the foundations of advocacy success. We found that the strongest indicator is a nonprofit’s research capacity. Those organizations that generated real research of their own were the most likely to be contacted by government officials.12

This may seem to indicate that if local advocacy groups are to maximize their effectiveness, they need to hire PhDs or other skilled researchers. Financially, this is beyond the reach of the vast majority of urban nonprofits. Nevertheless, advocacy groups staffed by volunteers contributing their time can still develop valuable research. In cities, a large proportion of all issues—such as economic development projects, rebuilding schools, or siting new facilities—involve one specific neighborhood. Neighborhood groups can find real experts (engineers, architects, college professors, librarians, planners, local historians, etc.) within their home turf. Moreover, city agencies are often strapped, with insufficient personnel to fully staff their own initiatives, and city councils are not like Congress, with its enormous staffing capacity. If you have something of substance to offer, people in government may ask for it!

Success also derives from staying in the game, because issues often take years to reach some sort of resolution. This is especially true of project planning around real estate development, transportation projects, and new public works. The roles of citizen groups and neighborhood associations are helped by formal regulatory requirements for citizen participation that derive from federal, state, and local laws.13 This process is brought to life in Susan Ostrander’s book Citizenship and Governance in a Changing City, on politics in Somerville, a city near Boston. She traces how citizen groups provided representation for neighborhood residents as the city slowly moved through its processes to consensus over redevelopment and mass transit issues. Groups did not find their voice right away but did succeed over time.14 As government officials try to “get to yes” with stakeholders, long-term collaborators with real expertise are the ideal negotiating partners.

Impact

Ultimately, the bottom line for determining what works in advocacy is impact on policy decisions. The evidence here is strong. My own work with Kent Portney, referenced earlier, systematically examined the impact of environmental advocacy on city government. For each of fifty cities studied, we had measures of policies and programs across thirty-eight areas relating to sustainability. Examples include industrial recycling, tax incentives for environmentally sensitive development, bike lanes, and brownfield remediation. The scores for sustainability efforts in each city were then linked to the level of advocacy, and the resulting measures showed a very strong positive relationship. In straightforward terms, the more citizen group advocacy was incorporated into the policy-making process, the more commitment the city showed to sustainability and environmental protection.15

Research that is more qualitative in nature is convincing, as well. To cite just one work, economist Joan Fitzgerald found citizen groups and neighborhood associations highly influential in transit-oriented development, urban economic revitalization, and sustainability policy. For example, neighborhood organizations in Los Angeles and Long Beach took the initiative to reduce pollution at the large ports there. Eventually, they allied with the Natural Resources Defense Council, and in turn formed part of the Coalition for Clean and Safe Ports. Fitzgerald concluded that this advocacy “has been instrumental not only in cleaning the ports but in improving the quality of jobs for port workers.”16

At the same time, success for citizen advocacy is difficult to define in precise terms, because it typically involves compromise. To sit at the bargaining table is to enter into a set of expectations as to openness to compromise. Yet, depending on the context, compromise may mean playing defense to the other side’s initiative. For a variety of reasons—not the least of which is a constant need to expand their tax base—cities have a bias toward development. This can entail tough choices. A Boston developer purchased a dilapidated building that used to be home to the Dainty Dot Hosiery factory. The builder planned to tear the building down and replace it with a high-rise containing 180 condominiums. The building sat on the edge of the city’s Chinatown, a small neighborhood characterized by modest buildings and hemmed in by an increasingly robust downtown business district. It is also home to a surprising number of neighborhood groups—Chinatown Main Street, the Chinatown Neighborhood Association, and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, to name a few. In a deal brokered by the mayor’s office, these citizen groups and the developer agreed to reduce the size of the building to 147 units (and make it 75 feet shorter); and, per the initial plan, 47 units of affordable housing would be constructed at another site.17 Was this a victory for the neighborhood groups? On one level, yes, because the developer compromised by reducing the building’s size; but on another, no, because the new building could only result in raising the underlying value of adjacent land, making it that much more difficult for the Chinese restaurants and grocery stores to survive over the long term.

Yet the bias toward development sometimes plays to the advantage of neighborhood groups. Efforts to revitalize the urban core often revolve around new amenities designed to attract young professionals away from adjoining suburbs. Relevant projects may involve light rail, transit-oriented development, innovation districts, newly designed “green” buildings, parks and recreation facilities, and an increased array of restaurants and entertainment venues. Researchers link such endeavors to city-level economic growth, adding to the incentives for cities to move in this direction.18 These initiatives create real leverage for neighborhood groups, as both business and government leaders need citizen support for moving forward with projects that may be costly, disruptive, and controversial.

This portrait of success is one tied to conventional politics. Saul Alinsky may be a source of inspiration for some neighborhood activists, but protest-oriented activity is difficult to sustain. Absent a level of outrage that can support a local movement for an extended period, the best strategy for a group is to be seen as a long-term collaborator on which city officials and business leaders can rely for accurate information.

Policy-making is complex, with many different actors participating in what is often a long and drawn-out process. Evaluating the precise impact of advocacy on a particular issue is difficult, but research is convincing as to what generally works. What we know is that to maximize effectiveness, nonprofit leaders should make choices that (1) commit resources to lobbying; (2) build an internal research capacity; and (3) ensure that the organization participates on an ongoing basis in mandated citizen participation programs. It’s reasonable to expect that such commitments will lead to increased access to government, respect of the private sector, and a seat at the bargaining table.

Notes

- Jeffrey M. Berry, “Urban Interest Groups,” in The Oxford Handbook of American Political Parties and Interest Groups, ed. L. Sandy Maisel and Jeffrey M. Berry (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2010), 502–15.

- Jeffrey M. Berry and Kent E. Portney, “The Group Basis of City Politics,” in Nonprofits and Advocacy: Engaging Community and Government in an Era of Retrenchment, ed. Robert J. Pekkanen, Steven Rathgeb Smith, and Yutaka Tsujinaka (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), 33.

- Ibid., 34–35.

- Frank R. Baumgartner et al., Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

- This contrasts with earlier models of city politics, where regimes transcended individual mayors. See Clarence N. Stone, Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946–1988 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1989).

- Kent E. Portney, Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously: Economic Development, the Environment, and Quality of Life in American Cities, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 291.

- Boston Urban Study Group, Who Rules Boston?: A Citizen’s Guide to Reclaiming the City (Boston: Institute for Democratic Socialism, 1984).

- Alan Ehrenhalt, The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City (New York: Vintage, 2013). First published 2012 by Knopf.

- Jeffrey M. Berry with David F. Arons, A Voice for Nonprofits: Engaging Community Government in an Era of Retrenchment (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2003), 59. Lobbying cannot be the primary focus of the organization, but even this isn’t much of a restriction, since few groups are only involved in trying to directly meet with legislators and convince them of a course of action. Many local groups don’t even bother to file papers of incorporation as a nonprofit because they don’t meet the income threshold and, thus, don’t face the strictures of sec. 501(c)(3) (which confers the right to grant tax deductibility to donors).

- Nicole P. Marwell, “Privatizing the Welfare State: Nonprofit Community-Based Organizations as Political Actors,” American Sociological Review 69, no. 2 (April 2004): 265–91.

- Jennifer E. Mosley, “From Skid Row to the Statehouse: How Nonprofit Homeless Service Providers Overcome Barriers to Policy Advocacy Involvement,” in Nonprofits and Advocacy, 111.

- Berry with Arons, A Voice for Nonprofits, 134–35.

- Archon Fung, Empowered Participation: Reinventing Urban Democracy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006).

- Susan A. Ostrander, Citizenship and Governance in a Changing City: Somerville, MA (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2013), 36–59.

- Jeffrey M. Berry and Kent E. Portney, “Sustainability and Interest Group Participation in City Politics,” Sustainability 5, no. 5 (May 2013): 2077–97. The data on city programs were derived from Portney’s research, and his aggregate rankings of cities can be found at OurGreenCities.com.

- Joan Fitzgerald, Emerald Cities: Urban Sustainability and Economic Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 151.

- Due to the changed market that resulted from the real-estate meltdown across the country, the design of the Dainty Dot project was changed again after this compromise. What was ultimately built was of the same scale but contained more units—all apartments, including studios, and some on-site affordable housing units. See Casey Ross, “Tower set to rise in Chinatown,” Boston Globe, March 10, 2012.

- Edward L. Glaeser, Jed Kolko, and Albert Saiz, “Consumer City,” Journal of Economic Geography 1, no. 1 (2001): 27–50.

Jeffrey M. Berry is the John Richard Skuse Professor of Political Science at Tufts University. He is author of A Voice for Nonprofits (with David Arons). Follow Berry at @JeffreyMBerry.