April 7, 2016; Siebel Scholars and American Academy of Arts & Sciences

During the Great Recession, state funding of nonprofit organizations, including colleges and universities, dropped precipitously. As the recession fades into memory, some states are slowly increasing their funding for higher education, but many cannot. Economic need is spurring the majority of public university leaders to advocate for additional government funding, be more efficient, and create new funding opportunities to close the gap.

Today, public research universities across the country educate 3.8 million students annually. As public institutions, they depend on government funding, particularly from states, to maintain the essential services students and communities depend on. But, state appropriations have dropped thirty-four percent in the last decade. Colleges and universities also continue to receive other public funding, including $3.5 trillion from the federal government in fiscal year 2013. Unlike the $65 billion from state appropriations, the majority of federal funding is project-based instead of general operating. A strong source of general operating funds is essential for a nimble, healthy nonprofit organization.

A college or university may be categorized as a nonprofit organization, similar to a homeless shelter or workforce training program, but tuition provides a strong revenue stream most other nonprofits can only dream of. Additionally, unlike state government agencies, public colleges and universities also have some flexibility administering the programs and services offered as well as in setting their employee salaries.

Beginning in January 2013, the American Academy of Arts & Sciences authored five reports documenting the dramatic shift in funding and advocating for state reinvestment. It released its final report last week, Public Research Universities Recommitting to Lincoln’s Vision: An Educational Compact for the 21st Century. (The title refers to President Lincoln’s creation of the public university system under the Morrill Act of 1862.) The report builds on the previous publications and presents recommendations to colleges, government leaders, and the communities that depend on these higher education institutions.

The ACAD frankly outlines two crucial recommendations to their institution members to maintain—and, in some cases, restore—public trust. The first, strengthening the institution’s governing board, has been identified by many, including the Nonprofit Quarterly, as necessary for many large nonprofits. The ACAD’s report quotes the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges:

While boards are not the source of the governance challenges facing higher education, changes to boards and their structure can lead to improved leadership across higher education—in setting goals, in using data to evaluate performance, and in making strategic investments in ways that create value.

Secondly, the report highlights the demand on public research universities to be more efficient with their resources rather than continuing to increase tuition and other fees. In the past, colleges and universities raised tuition and fees to make up for the decrease in government funding and increase in other program expenses. Now, as student debt rises to record levels, the public backlash from these increases has reached a critical juncture. Eighty-three percent of all first-year students receive some form of financial aid, and 71 percent receive federal, state, local, or institutional grant aid. Even with all of these scholarships and aid programs, in 2012-2013, 54 percent of undergraduate students graduated with student loan debt and 19 percent had student loan debt over $25,000. Continuing to raise tuition will lead to a lack of diversity and a further decrease in public trust.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Connected to the growing use of public aid, the ACAD recognized the need to make applying for financial aid easier for students and their families. Every year, sixteen million students apply for financial aid through the U.S. Department of Education’s Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) program, including Pell Grants, Work Study, and other essential federal aid opportunities. Currently, the application consists of 108 questions and 88 pages of instructions. Clearly, simplifying this process will open college up to more low income and first-generation college students. (44,45)

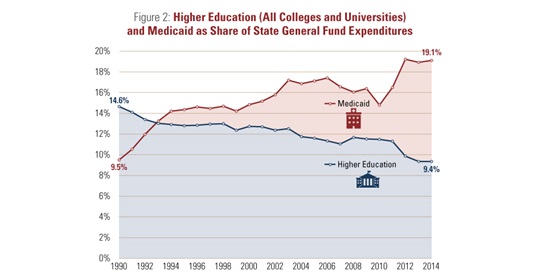

ACAD makes a strong plea to state governments to reinstate funding for their college and university systems that was reduced before and during the recent recession. Although higher education remains the third-largest state priority, funding has declined an average of 34 percent nationwide over the last fifteen years. In that same period, state funding of Medicaid has increased from 9.5 percent to 19.1 percent of state budgets, overtaking and sucking away higher education’s allocation.

Since the higher levels of state public funding revenue are a distant memory, colleges and universities are developing new funding opportunities and efficiencies through collaborations with other nearby schools and public-private partnerships. These efforts begin with making it easier for students to transfer between state institutions. Other developments include programs that stretch resources of multiple universities to create exciting new programs and opportunities for students to learn together, connect with professors and mentors at multiple schools, and expand research efforts. For example, three colleges (the College of Engineering at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, the Wake Forest School of Medicine, and the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine) established a joint graduate program in the Virginia Tech–Wake Forest University School of Biomedical Engineering and Sciences, offering students access to all three campuses.

Public research universities are also creating new partnerships with corporations and other private organizations. These collaborations lead to expanded research activities, new courses and department chairs, internships, and scholarships. Additionally, colleges are also stepping up their own development activities. Of the seventy-seven institutions responding to the Lincoln Project’s survey, ninety percent recently completed or are in the midst of a capital campaign for one or more institutional purposes.

Finally, colleges are increasing the revenue they produce from related student expenses, including food, dormitories, and healthcare. Dorms are becoming more luxurious; food is more expensive; fees are growing, and health services fees in particular are on the rise. Overall, student fees and tuition make up more than half of a public university’s core educational support. And like tuition, schools are quickly realizing these extra fees decrease diversity, increase student debt, and lead to public backlash.

Public research colleges and universities are better equipped than many nonprofits to handle the shift in states’ funding priorities due to their access to alumni and other stakeholders with resources to support fund development efforts. This capacity, however, does not excuse states from providing enthusiastic support and increasing funding to assure the sustainability and growth of public universities for at least the next 150 years.—Gayle Nelson