Editors’ note: This article, first published in print during Nov/Dec 2013, has been republished for Nonprofit Quarterly with minor updates.

WITH THE NEW YEAR APPROACHING, many of us are thinking about personal goals, resolutions, and new projects. This is the perfect time to apply some of this self-improvement thinking to your organization’s approach to budgeting for fundraising.

It may be tempting for nonprofit leaders to focus solely on the revenue generating aspect of development. But taking a comprehensive look at the expenses associated with raising funds for your organization’s mission—and coordinating this process with programmatic and administrative budgeting—will reap long-term rewards. In Fiscal Management Associates’ (FMA) work with thousands of nonprofits across the country, we have found that organizations that follow these five budgeting principles realize improvements in financial sustainability, staff communication, and the ability to tell their unique story through financials.

1.Make budgeting a team effort.

Ensure that development has a seat at the financial planning and budgeting table. Budgeting is often considered an unenviable task for the finance staff with development staff asked to only provide revenue estimates. The simple step of involving your development lead in the full budgeting process will increase their comfort level in explaining your organization through numbers. That is really what a budget is—an organization’s plan for executing its mission quantified in dollars.

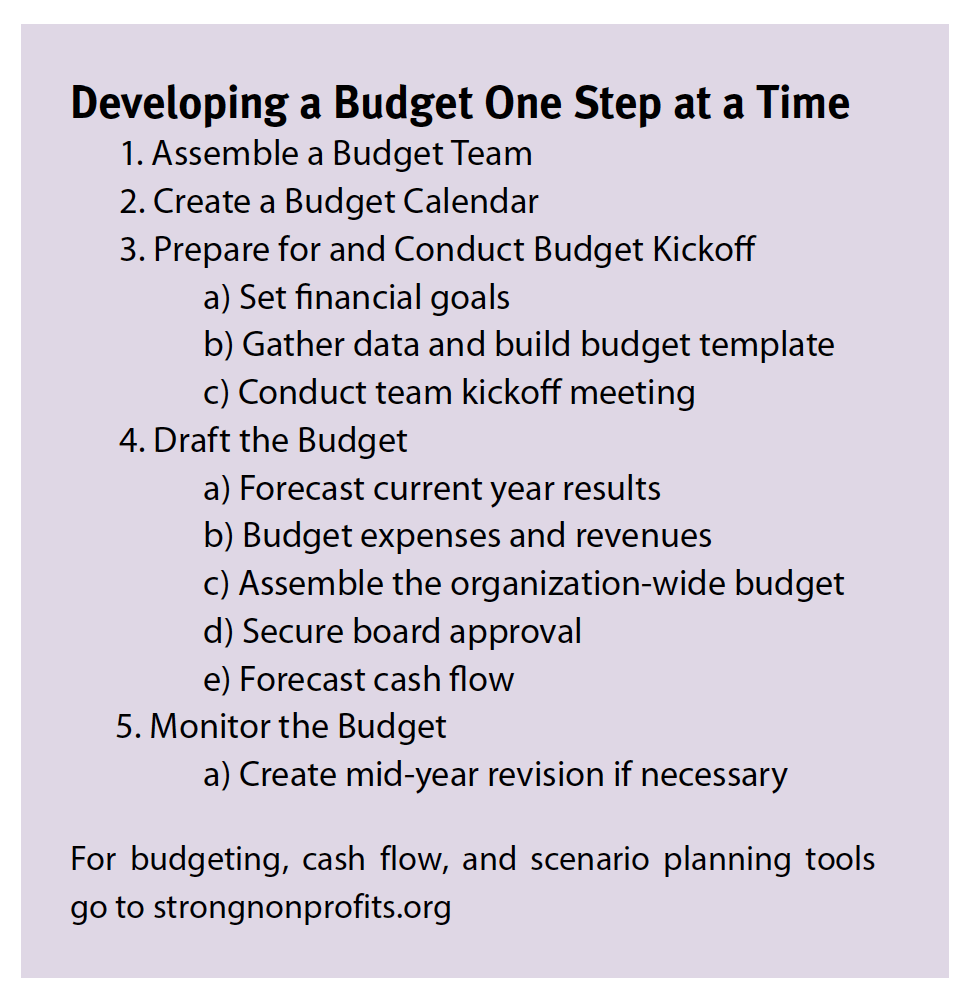

A strong budgeting team is typically led by the executive director with support from a finance or operations staff person (if an organization has one), and rounded out by development, program, and other departmental directors. The annual budget development process begins with a team kickoff meeting, culminates in a board-approved budget, and continues with budget-to-actual monitoring throughout the fiscal year. See the sidebar on the next page for a step-by-step guide to share with the leaders of your budget team.

2. Start your budgeting process by projecting expenses.

Projecting expenses helps team members focus on what the organization wants to accomplish rather than what they feel can be done given anticipated funding constraints or what the organization typically does each year.

Divide expenses into two categories—annual costs and one-time investments. Projections for ongoing costs like web design, supplies, and donor cultivation should be based on reliable historical financial data as well as relevant information about future activities such as your annual fundraising plan. Projections for annual costs like these should be made for each program, development, and administration.

One-time or new expenses that are not currently in place such as a new donor database or additional staffing fall into the category of longer-term investments in infrastructure. Some may find their way into this year’s budget, some onto a wish list for the future, and, occasionally, some may become part of a capital project budget. The beauty of the team-based approach is that your desired infrastructure investments can be coordinated with outlays in other areas to maximize efficiencies (e.g., upgrading to compatible accounting and fundraising software at the same time). Large costs can also be staged out over a few years to spread expenditures out over time.

Do you have a strategic plan in place? Don’t forget to include any costs associated with fundraising-related goals and initiatives.

3. Estimate revenues.

This piece of the budgeting process is probably the most familiar. But predicting the somewhat unpredictable is still a big task. To make revenue projections more productive and less painful, we go back to the principle of using reliable past financial data (where have we been?) and information about future activities (where are we going?) to make realistic predictions.

For grants, differentiate between committed funds and pending proposals, using your knowledge of the funder relationship and specific proposal to estimate the likelihood of success for each pending application. For individual donors, you can estimate the volume of funding by donor category (major donors, special events, members) based on the number of donors and average gift amount in previous years. You should also factor in any change in attendance, giving levels, or total donors implied by the coming year’s fundraising plan.

This data-based approach is helpful if there is pressure from the team to change projections. You can easily model suggested changes and what it would take to get there (e.g., X more new members each month, Y more gala attendees).

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Finally, remember to include in-kind revenues (and match-ing expenses). And don’t forget to ensure projections reflect any strategic plan revenue goals!

4. Match revenues to expenses.

While this may seem like an obvious step, it is where we often see the budgeting process break down. The budget team members have all contributed their best-case plans for the year expressed in a program/department expense budget and may feel like slinking away and letting the budget lead put the whole mess together. Yes, the budget lead will do the heavy lifting, compiling development, program, and administrative budgets into an organization-wide annual budget draft. But it is important for the team to stay engaged and work through the often iterative process of reconciling projected revenues to anticipated expenses.

Development has a special responsibility in this process: track-ing donor restrictions on when and for which program(s) funds can be used. This means knowing whether that $15,000 pledge is intended for the coming fiscal year or is meant to be spread across three years, and whether it must be spent only on advocacy or training activities. The team will look to development to track restricted revenues and associated expenses. On the revenue side, you should maintain both the annual budget perspective (how much revenue will we have for use this fiscal year?) and the cash flow perspective (when is that grant expected to arrive?).

On the team level, this is when you might have to start making tough choices and cutting expenses. Cutting expenses is never fun. But this is where the power of the team and advance planning comes into play. Talking through contingencies now in a thoughtful, strategic way is guaranteed to have better results than waiting to make important decisions quickly in a time of stress.

Scenario Planning

Here is a step-by-step guide to scenario planning for the team to use to match revenues to expenses and start the conversation around potential changes to the draft budget:

- Use the revenue projections developed in step 3.

- Play out three different scenarios for uncertain revenues across three columns with a “best case” picture, a most likely or “baseline” estimate, and a “worst case” in which most revenue categories underperform.

- Enter your full, organization-wide expense budget in each column.

- Analyze the bottom line—is there a surplus, break-even result, or deficit in the best-case column? Ask the same question for the other two columns. Remember to consider the organization’s multi-year strategic plan and annual goals: What is the organization aiming for this year? Is a surplus necessary to stay on track with long-term goals? Is there a compelling reason to draw from operating reserves and incur a small, planned deficit this year?

- Prioritize potential cuts if necessary. Discuss and agree upon which expense line items could potentially be reduced, eliminated or accomplished in a different way or at a different time. If cuts are not necessary now but may become necessary if pending revenues do not reach certain targets, then set “milestone” dates when decisions must be made or pre-determined cuts must take place.

- Finalize the budget, engage the board in a discussion about budget assumptions, and secure the board’s approval in advance of the start of your fiscal year.

5. Monitor the budget: make sure you can see the forest and the trees.

We are working with a conservation organization right now on quantifying their strategic vision in dollars. Their programming goals are very clearly spelled out and include planning and maintaining the forest and monitoring the trees in their region. While few organizations have such a convenient reminder, we could all do well to remember the old “not seeing the forest for the trees” saying when engaging in financial planning and monitoring. The forest is your annual budget and the trees are the revenue and expense components.

Your finance staff should provide a budget-to-actual report for development on a monthly or quarterly basis with a variance column showing the percentage of actual revenue and expense items compared to the budget for each major category. Finance staff should also provide some training on reading and interpreting these reports if you are not familiar with them. Once you are comfortable reading the report, it is time to think about some key questions regarding your forest and trees:

- Forest (annual development budget)

- Are total fundraising expenses to-date on pace with expectations? Are variances between actual spending and the budget for major expense categories in this area explainable?

- Are major revenue categories on track?

- Trees (revenue and expense line items)

- Does the percentage spent so far on each line item match your expectations (e.g., does it make sense that 70 per-cent of your supplies budget has been used in the first quarter?)? Do you understand what each line item contains?

- Are your major donor gifts arriving when expected? Does a variance in foundation support indicate a change in the timing of a receivable? Do any changes indicate a need to update cash flow expectations?

As you get used to reviewing budget reports on a regular basis, it will become easier to “eyeball” them, taking in both the forest and the trees relatively quickly. Unexpected results will become more obvious, and you will know when to ask questions or revisit assumptions.

You may now feel like we duped you. We started by talking about five steps for fundraising budgeting and ended up unfold-ing an entire annual budgeting plan. But even if you focus on just the first step, empowering development to be part of the organization-wide budgeting process, you will see benefits. This will help connect your fundraising plan to the tangible steps and costs it will take to implement it. And by spending some time thinking about the costs associated with development (and bringing these to the full team’s attention through approaching budgeting together), you can make an internal pitch for investing in the day-to-day needs, infrastructure improvements, and internal capacity necessary to make your development efforts as efficient and effective as they can be.

Dipty Jain leads the Consulting Services team at Fiscal Management Associates (FMA). Kate Garroway leads FMA’s Cohort and Initiative programs for philanthropic organizations and their nonprofit partners.