December 1, 2017; National Public Radio, “All Things Considered”

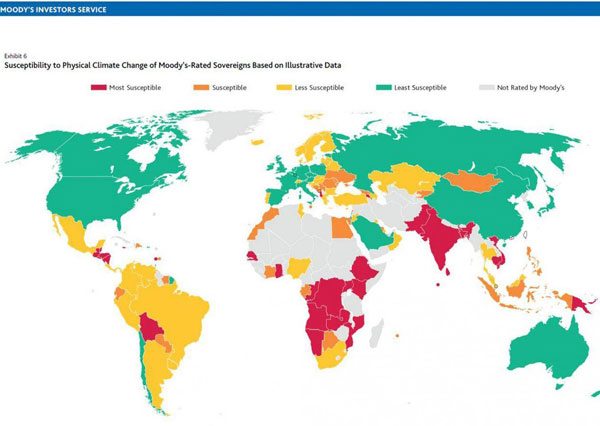

As reported by Nathan Rott on National Public Radio’s flagship program, All Things Considered, Moody’s Investor Services, Inc., “one of the largest credit rating agencies in the country,” has issued a warning to US cities and states to prepare for climate change or risk finding themselves facing significantly higher interest rates when they wish to borrow funds.

Last month in NPQ, Bhakti Mirchandani wrote about similar trends facing the corporate world. Mirchandani noted that the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure, a group established at the request of the head of the Bank of England, who called for greater transparency “on the risks that climate change may impose on the financial condition of companies,” issued a series of recommendations this past June. Among them was the recommendation that “preparers of climate-related financial disclosures provide [climate risk] disclosures in their public annual financial filings,” which should include disclosures related to “climate-related governance, strategy, risk mitigation, and metrics and targets.”

Moody’s has focused on state and municipal bonds, but the impact of its announcement may well extend even further. As Moody’s explained in a public summary of its report, “The growing effects of climate change, including climbing global temperatures, and rising sea levels, are forecast to have an increasing economic impact on US state and local issuers. This will be a growing negative credit factor for issuers without sufficient adaptation and mitigation strategies.”

Estimating risk is an imprecise science, of course, but not impossible. Famously, when asked in early 2001 to name “the three likeliest, most catastrophic disasters” facing the US, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)’s top three were a terrorist attack on New York City, a hurricane in New Orleans, and a massive earthquake in San Francisco. Within five years, FEMA, not known for its powers of prognostication, had sadly gone two-for-three.

As for Moody’s predictions in 2017, Rott outlines what the agency is anticipating:

In its report, Moody’s breaks the US into seven “climate regions,” based off of geography, regional economies and expected risks.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In the Midwest, “impacts on agriculture are forecast to be among the most significant economic effects of climate change,” the report says.

The Southwest is projected to become more vulnerable to extreme heat, drought, rising sea levels and wildfires.

Rising sea levels and their effect on coastal infrastructure is the biggest forecast impact on the Northeast.

Rott adds, “Communities that face a high risk of being seriously impacted by the impacts of climate change are being asked by analysts during the rating process how they’re preparing for these risks.” For example, in Broward County, Florida (just north of Miami), chief resilience officer Jennifer Jurato says the county received surveys from Moody’s regarding “how the community and local government [were] responding to issues of sea-level rise and flood protection.”

Michael Wertz, a vice president at Moody’s, notes that, “If you have a place that simply throws up its hands in the face of changes to climate trends, then we have to sort of evaluate it on an ongoing basis to see how that abdication of response actually translates to changes in its credit profile.”

Rachel Cleetus, lead economist and climate policy manager at the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists, underscores the importance of Moody’s shift.

This puts a direct economic incentive [for communities] to take protective measures against climate change…[It’s just the latest] market-based signal that what seemed like a far-off distant future gets collapsed into the present and that people have to start making decisions now based on what is already baked in reality for many of these places.

—Steve Dubb