June 19, 2020; Washington Post

Writing for the Washington Post, Drew Jones reports that dozens of museums are “rushing to chronicle and contextualize American history, right as it’s being made.”

“History isn’t just about keeping records of random events,” Aaron Bryant, a photography and social protest historian at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), tells Jones.

Bryant adds that the museum understands the uprising spurred by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others is a historical event. That means the museum has a curatorial responsibility, even as COVID-19 keeps its doors closed. The work of the museum “is really about documenting and evaluating the evolution of human progress and our humanity. This moment would be a part of that story.”

This is not the first time that NPQ has reported on museums acting to curate the present. Back in 2017, NPQ’s Erin Rubin wrote about an exhibit at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) that featured signs from the Standing Rock protests as part of an exhibit on the ongoing Native American struggle for sovereignty. Rubin also noted that “the New-York Historical Society, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and others have been known to send staff to protests and other events to gather memorabilia.”

How does a museum engage in this work during a pandemic? Sometimes, it’s through digital crowdsourcing. For example, the NMAAHC “is asking protesters to digitally upload protest-related pictures, videos and audio recordings and hold on to physical objects such as signs, T-shirts and artwork for future donation.” The Houston Museum of African American Culture (HMAAC), in George Floyd’s hometown, is using social media to garner submissions, asking users to #preservetheculture through photos and stories documenting their communities.

For its part, the New-York Historical Society has its History Responds initiative posted to its website. The museum call seeks items from both the protests and the pandemic. For the Black Lives Matter protests, the call includes the following prompts.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- “Are you observing the protests and taking photographs of your favorite signs?”

- “Are you participating in the protests and creating your own signs, flyers, posters, or hand-painted T-shirts?”

- “Are you collecting signs and placards or leaflets and flyers about upcoming protests?”

- “Are you wearing masks with political messages or protective eyewear in case of pepper spray or tear gas?”

Regarding the pandemic, the museum website also includes a number of prompts:

- “Are you keeping a diary, making lists, or taking photographs that reflect sheltering in place?”

- “Do your food-delivery menus, apartment-building notices, or neighborhood flyers reference the pandemic?”

- “Have you gotten COVID-19 mass emails from banks, restaurants, or rental car companies?”

- “Are you drawing, making collages, or painting?”

For those who have relevant items with which they are willing to part, an online material donation form can be filled out to begin the item donation process.

At the Smithsonian, Bryant says his curatorial goal is to uplift historically marginalized voices. Tina Burnside, a civil rights attorney and curator for the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery (MAAHMG), articulates similar goals.

“A lot of times, when historical moments are told, they’re usually told from the perspective of white people,” Burnside relates to Jones. “They’re the ones writing the narratives, even if it happens to African Americans, so it’s very important to document the voices of Black people that are ignored or often not heard.”

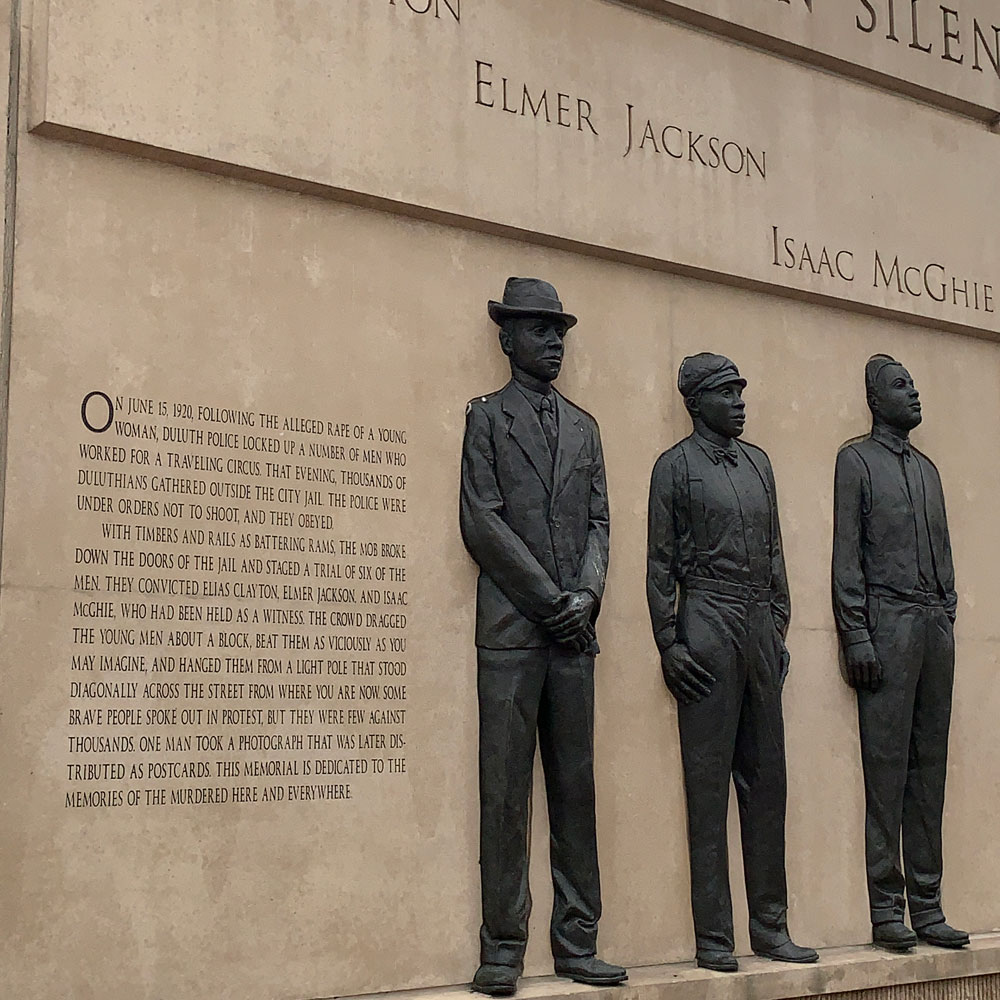

The MAAHMG, located in Minneapolis, will showcase two new exhibits on racism in the state when it reopens (currently expected to happen in July). The first, Jones writes, “will be a commemoration of the 100th anniversary of a 1920 Duluth lynching of three black men: Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie. The second will be an interactive exhibit on the Floyd memorial in Minneapolis, filled with protester interviews and a series of photographs from the site.”

The exhibits seek to advance the mission of the museum—the first of its kind in the state—to expose visitors both to the deep injustices Blacks have faced in Minnesota and to their countless contributions to it.

“Minnesota has always been known as a very progressive state, but beneath that progressive exterior, there have been a lot of racial problems, and it hasn’t been dealt with,” Burnside tells Jones. “I want people to start to really try to understand what has caused this movement—the problems, the disparities, the pain, the emotion, and why people are reacting the way that they are—and not to casually dismiss it, but really try to understand what is going on so that we can move forward to work on solutions.”—Steve Dubb