April 6, 2015; Texas Tribune

It’s lucky for this author that his grandparents and great-grandparents weren’t skewered by immigration officials for appropriate documents when the immigration to the U.S. It’s hard to imagine that large numbers of the people passing through Ellis Island in those days weren’t what would be called in today’s political parlance “illegal immigrants.” (At NPQ, we prefer “undocumented.”) Making do with menial jobs, raising their children and grandchildren in Brooklyn neighborhoods, they had plenty of challenges to overcome without being constantly carded by local police, but unlike many of today’s undocumented immigrants, they weren’t Latinos or other people of color and therefore didn’t stand out as different by virtue of their skin color to be picked up at a whim to fear deportation.

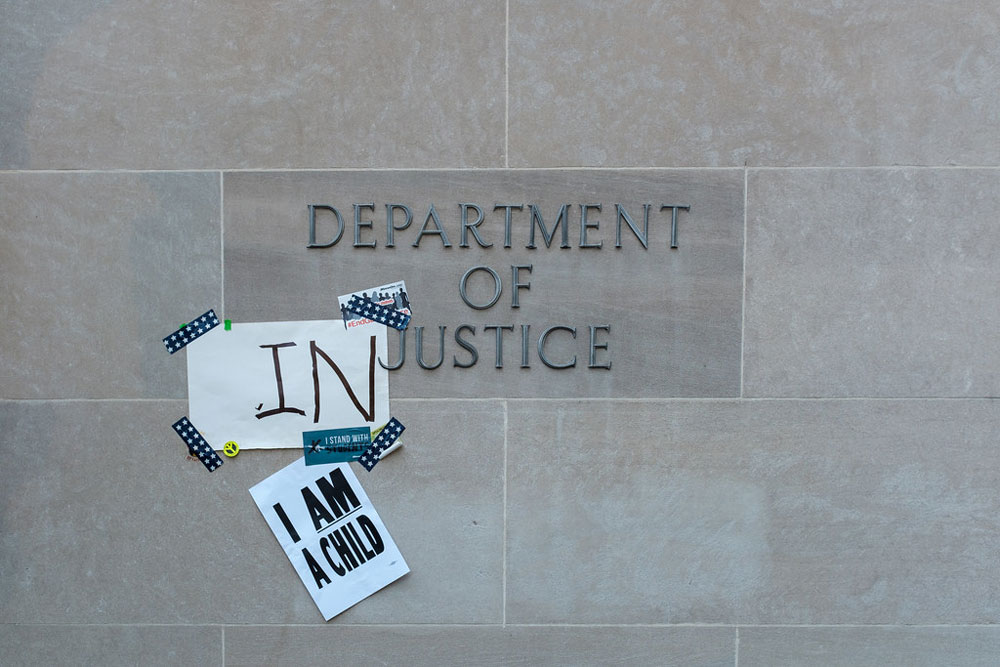

Was New York City a “sanctuary” city in those days? Its city fathers probably didn’t think of the place in that manner. There actually doesn’t seem to be any kind of legal definition of what a sanctuary city might be, but that isn’t stopping the Texas state legislature from trying to outlaw them, part of a draconian suite of bills meant to put Texas state and local cops on the beat to find undocumented immigrants. Last month, the legislature was considering House Bill 11, which would have made people legally vulnerable for driving undocumented immigrants around, whether simply giving someone who happened to be undocumented a lift or offering a ride to an undocumented family member or transporting undocumented immigrants as part of a human smuggling operation. After hearing the outcries of nonprofits and faith-based entities that would have been prosecuted simply for providing a transportation service to an undocumented person, legislators amended the bill to supposedly alleviate the concerns of churches. The new language addresses people or entities that might “knowingly” give an undocumented immigrant a ride—with profit as the motive. It seems that faith-based nonprofits and churches still have problems with the bill, particularly language that suggests legal culpability for those who are charged with having “induced” undocumented immigrants to cross the Rio Grande.

Now comes Senate Bill 185, introduced by state senator Charles Perry, a Republican from Lubbock, that would “cut off state funding for local governments or governmental entities that adopt policies that forbid peace officers from inquiring into the immigration status of a person detained or arrested,” as summarized by Julián Aguilar in the Texas Tribune. This isn’t the first time this kind of statute has been considered by the Texas legislature. An earlier version in 2011 failed to pass due to charges that the legislation would encourage racial profiling and deter undocumented immigrants from cooperating with law enforcement as witnesses to crimes.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

To make the law more acceptable, this new version that has been passed by a House subcommittee and now goes to the full committee has been modified to exempt “open enrollment charter schools” as well as “commissioned peace officers” from having to promise to chase down and report undocumented immigrants. It also doesn’t apply, in the new version, to victims or witnesses of crime. Try to imagine how that would operate, where an undocumented immigrant would present himself or herself as a victim or witness and not find themselves vulnerable at some time down the line to anti-immigrant prosecution. Senator Perry believes that the bill is simply a measure that would go after undocumented immigrants who are in the U.S. with an intent to cause harm to others, but that interpretation is impossible to reach in the language of the bill.

Jeffrey Bradshaw, a young writer for the University Star, the independent student newspaper of Texas State University, says that there are 15 sanctuary cities in Texas. The Perry bill would make all of these cities and probably others vulnerable to losing state funding were they to continue their municipal government policies of refraining from using local police to chase down potential undocumented immigrants. Similar legislation appears occasionally at the federal level. We remember the Mobilizing Against Sanctuary Cities Act of 2011, introduced by Rep. Lou Barletta (R-PA), attracting as one of its five co-sponsors Rep. Steve King (R-IA), widely seen as a top anti-immigrant (and anti-immigration) member of Congress. Barletta had been mayor of Hazleton, Pennsylvania, which enacted a platform of anti-immigrant bills to punish landlords and employers who might rent to or hire undocumented immigrants, though litigation filed by the ACLU stopped Barletta from proceeding. Helping out in the sentiment of attacking sanctuary cities, ALEC has long proposed a template for a “No Sanctuary Cities for Illegal Immigrants Act” that motivated legislators like Perry, Barletta, and King could emulate.

The cities that Perry is targeting with his bill are, in the minds of anti-sanctuary advocates, magnets that attract undocumented immigrants to the U.S., as though undocumented immigrants would somehow be induced by them rather than motives more along the lines of finding work and earning money to support their families. Interestingly, some of the most active sanctuary cities, particularly San Francisco, while not devoting their police forces to anti-immigrant patrols, do not preclude cooperating with federal ICE officers, and their sanctuary city status has not resulted in violations of the Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (the applicable federal law at the moment).

Perry implies that his bill would have Texas municipal authorities go after undocumented immigrants involved in or supporting criminal behavior, but it seems the bill doesn’t do that. The bill would, however, lead to pressures for racial profiling and against the provision of human services to immigrants. If NPQ readers have experience with sanctuary cities and what they do and don’t do, we’d like to hear.—Rick Cohen